Administrative Law by Carlo Cruz Lecture PDF

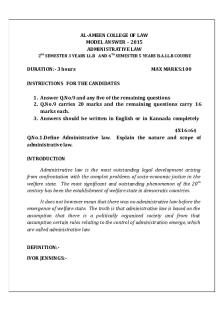

| Title | Administrative Law by Carlo Cruz Lecture |

|---|---|

| Author | Anne Derramas |

| Course | Juris Doctor |

| Institution | San Beda College Alabang |

| Pages | 10 |

| File Size | 206.9 KB |

| File Type | |

| Total Downloads | 167 |

| Total Views | 243 |

Summary

Aratuc vs. COMELEC Aratuc sought the suspension of the canvass then being undertaken by the respondent Board in Cotabato City. The petitioners in the instant case filed complaints re allege irregularities in the election records in the voting centers in Region 12. Before the start of the hearings, t...

Description

1. Aratuc vs. COMELEC Aratuc sought the suspension of the canvass then being undertaken by the respondent Board in Cotabato City. The petitioners in the instant case filed complaints re allege irregularities in the election records in the voting centers in Region 12. Before the start of the hearings, the canvass was suspended but after the supervisory panel presented its report, COMELEC filed its order of suspension and directed the resumption of the canvass to be done in Manila. The Regional Board of Canvassers issued a resolution, over the objection of the KB candidates, declaring all the 8 KBL candidates elected. Appeal was taken by the KB candidates to the Comelec. On January 13, 1979, the Comelec issued its questioned resolution declaring seven KBL candidates and one KB candidate as having obtained the first eight places as representatives of Batasang Pambansa; and ordering the Regional Board of Canvassers to proclaim the winning candidates. The KB candidates interposed the present petition. ISSUE: Whether or not the COMELEC grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack of jurisdiction. HELD: NO. COMELEC may deem manufactures the returns showing that votes exceeded the highest number of valid votes; and could extend its inquiry beyond that undertaken by the Board of Canvassers. Comelec considered the high percentage of voting and mass substitute voting as proof that returns have been manufactured. As the Superior administrative body having control over boards of canvassers, the Comelec may review the actuations of the Regional Board of Canvassers, such as by extending its inquiry beyond the election records of the voting centers in questions.” “The authority of the Commission is in reviewing such actuations does not spring from any appellant jurisdiction conferred by any provisions of the law, for there is none such provision anywhere in the election Code, but from the plenary prerogative of direct control and supervision endowed to it by the provisions in Section 168. And in administrative law, it is a too well settled postulate to need any supporting citation here, that a superior body or office having supervision and control over another may do directly what the latter is supposed to do or ought to have done. 2. Maceda v. Energy Regulatory Board FACTS: Petitioners pray for injunctive relief to stop the ERB from implementing its Order mandating a provisional increase in the prices of petroleum. Order issued with grave abuse of discretion and without proper notice and hearing pursuant to E.O. 172. ISSUE: Whether or not ERB orders granting provisional oil increase without prior notice is valid. HELD: Yes, it is valid. While E.O 172, a hearing is indispensable, it does not preclude the board from ordering ex-parte, a provisional increase, subject to final disposition of whether or not: to make it permanent; to reduce or increase it further; to deny the application. Sec 3e – Board determine that there is a shortage of petroleum product, may take necessary steps like tempo adjustment of prices. Sec 8 – Board may grant provisional relief based on documents submitted that substantially support the provisional order. Sec. 3e is akin to temporary restraining order. It outlines the jurisdiction of the grounds for which it may decree a price adjustment, subject of notice and hearing. However, under Sec. 8, it may order the price increase provisionally, without need of hearing, subject to final outcome of the proceeding. The Board is not prevented from conducting a hearing on the grant of provisional authority, however, it cannot be stigmatized later if it failed to conduct one.

3. US v. Dorr 4. Malaga v. Penachos Jr. FACTS: The Iloilo State College of Fisheries (ISCOF) through its Pre-qualifications, Bids and Awards Committee (PBAC) caused the publication for an Invitation to Bid for the construction of a Micro Laboratory Building. The notice announced that the last day for the submission of pre-qualification requirements was on December 2, 1988, and that the bids would be received and opened on December 12, 1988 at 3pm. Petitioners Malaga and Najarro, doing business under the name of BE Construction and Best Built Construction, respectively, submitted their pre-qualification documents at 2pm of December 2, 1988. Petitioner Occeana submitted his own PRE-C1 on December 5, 1988. All three of them were not allowed to participate in the bidding as their documents were considered late. The petitioners filed a complaint with the Iloilo RTC against the officers of PBAC for their refusal without just cause to accept them resulting to their non-inclusion in the list of pre-qualified bidders. They sought to the resetting of the December 12, 1988 bidding and the acceptance of their documents. They also asked that if the bidding had already been conducted, the defendants be directed not to award the project pending resolution of their complaint. On the same date, Judge Lebaquin issued a restraining order prohibiting PBAC from conducting the bidding and award the project. The defendants filed a motion to lift the restraining order on the ground that the court is prohibited from issuing such order in government infrastructure project under Sec. 1 of P.D. 1818. They also contended that the preliminary injunction had become moot and academic as it was served after the bidding had been awarded and closed. On January 2, 1989, the trial court lifted the restraining order and denied the petition for preliminary injunction. It declared that the building sought to be constructed at the ISCOF was an infrastructure project of the government falling within the coverage of the subject law. ISSUE: Whether or not ISCOF is a government instrumentality subject to the provisions of PD 1818? RULING: The 1987 Administrative Code defines a government instrumentality as follows: Instrumentality refers to any agency of the National Government, not integrated within the department framework, vested with special functions or jurisdiction by law, endowed with some if not all corporate powers, administering special funds, and enjoying operational autonomy, usually through a charter. This term includes regulatory agencies, chartered institutions, and government-owned or controlled corporations. (Sec. 2 (5) Introductory Provisions). The same Code describes a chartered institution thus: Chartered institution - refers to any agency organized or operating under a special charter, and vested by law with functions relating to specific constitutional policies or objectives. This term includes the state universities and colleges, and the monetary authority of the state. (Sec. 2 (12) Introductory Provisions).

It is clear from the above definitions that ISCOF is a chartered institution and is therefore covered by P.D. 1818. There are also indications in its charter that ISCOF is a government instrumentality. First, it was created in pursuance of the integrated fisheries development policy of the State, a priority program of the government to effect the socio-economic life of the nation. Second, the Treasurer of the Republic of the Philippines shall also be the ex-officio Treasurer of the state college with its accounts and expenses to be audited by the Commission on Audit or its duly authorized representative. Third, heads of bureaus and offices of the National Government are authorized to loan or transfer to it, upon request of the president of the state college, such apparatus, equipment, or supplies and even the services of such employees as can be spared without serious detriment to public service. Lastly, an additional amount of P1.5M had been appropriated out of the funds of the National Treasury and it was also decreed in its charter that the funds and maintenance of the state college would henceforth be included in the General Appropriations Law. Nevertheless, it does not automatically follow that ISCOF is covered by the prohibition in the said decree as there are irregularities present surrounding the transaction that justified the injunction issued as regards to the bidding and the award of the project (citing the case of Datiles vs. Sucaldito). HOWEVER, it is apparent that the present controversy did not arise from the discretionary acts of the administrative body nor does it involve merely technical matters. What is involved here is noncompliance with the procedural rules on bidding which required strict observance. PD 1818 was not intended to shield from judicial scrutiny irregularities committed by administrative agencies such as the anomalies in the present case. Hence, the challenged restraining order was not improperly issued by the respondent judge and the writ of preliminary injunction should not have been denied. 5. Beja Sr. v. CA FACTS: Petition questions the jurisdiction of Sec of DOTC and its Administrative Action Board over cases involving personnel below the rank of Assistant General Manager of the Philippine Ports Authority which is an agency attached to the Department. Beja Sr. was first employed by PPA as arrastre supervisor then became terminal supervisor. General Manager Dayan filed admin case against Beja and Villaluz for grave dishonesty in erroneously assessing storage fees resulting in the loss of Php38k on PPA. They were preventively suspended. After PI, case was closed for lack of merit. Another case was filed against Beja for dishonesty; consists of 6 specifications of admin offenses including fraud against PPA in the amount of Php218k. Beja was placed under preventive suspension. PPA indorsed it to the AAB for appropriate action. The AAB proceeded to hear the case and gave Beja an opportunity to present evidence. Beja filed petition for certiorari with preliminary injunction before the RTC. Two days later, he filed with the ABB a manifestation and motion to suspend the hearing of administrative case on account of the pendency of the certiorari proceeding before the court. AAB denied the motion and continued with the hearing of the administrative case. Thereafter, Beja moved for the dismissal of the certiorari case and proceeded to file before the Court for a petition for certiorari with preliminary injunction and/or temporary restraining order.

ISSUE: Wether or not the Administrative Action Board of DOTC has jurisdiction over administrative cases involving personnel below the rank of Assistant General Manager of the Philippine Ports Authority, an attached agency of DOTC for program and policy coordination. HELD: PPA was created through P.D. 505; the corporate powers of PPA were vested un the BOD known as PPA Council. The council has the power to appoint, discipline and remove personnel. P.D. 505 was substituted by P.D. 857 and created PPA which would be attached to then DPWTC. Admin Code classified PPA as attached agency to DOTC. Transmittal of the complaint by the PPA General Manager to AAB was premature. The manager should have first conducted an investigation, made proper recommendation for the imposable penalty and sought its approval by the PPA Board of Directors. 6. Eugenio v. CSC FACTS: FACTS: Eugenio is the Deputy Director of the Philippine Nuclear Research Institute. She applied for a Career Executive Service (CES) Eligibility and a CESO rank,. She was given a CES eligibility and was recommended to the President for a CESO rank by the Career Executive Service Board. Then respondent CSC passed a Resolution which abolished the CESB, relying on the provisions of Section 17, Title I, Subtitle A. Book V of the Administrative Code of 1987 allegedly conferring on the Commission the power and authority to effect changes in its organization as the need arises. Said resolution states: “Pursuant thereto, the Career Executive Service Board, shall now be known as the Office for Career Executive Service of the Civil Service Commission. Accordingly, the existing personnel, budget, properties and equipment of the Career Executive Service Board shall now form part of the Office for Career Executive Service.” Finding herself bereft of further administrative relief as the Career Executive Service Board which recommended her CESO Rank IV has been abolished, petitioner filed the petition to annul, among others, said resolution. ISSUE: WON CSC given the authority to abolish the office of the CESB HELD: NO 1. The controlling fact is that the CESB was created in PD No. 1 on September 1, 1974 . It cannot be disputed, therefore, that as the CESB was created by law, it can only be abolished by the legislature. This follows an unbroken stream of rulings that the creation and abolition of public offices is primarily a legislative function In the petition at bench, the legislature has not enacted any law authorizing the abolition of the CESB. On the contrary, in all the General Appropriations Acts from 1975 to 1993, the legislature has set aside funds for the operation of CESB. Respondent Commission, however, invokes Section 17, Chapter 3, Subtitle A. Title I, Book V of the Administrative Code of 1987 as the source of its power to abolish the CESB. But as well pointed out by petitioner and the Solicitor General, Section 17 must be read together with Section 16 of the said Code which enumerates the offices under the respondent Commission.

As read together, the inescapable conclusion is that respondent Commission’s power to reorganize is limited to offices under its control as enumerated in Section 16.. 2. From its inception, the CESB was intended to be an autonomous entity, albeit administratively attached to respondent Commission. As conceptualized by the Reorganization Committee “the CESB shall be autonomous. It is expected to view the problem of building up executive manpower in the government with a broad and positive outlook.” The essential autonomous character of the CESB is not negated by its attachment to respondent Commission. By said attachment, CESB was not made to fall within the control of respondent Commission. Under the Administrative Code of 1987, the purpose of attaching one functionally interrelated government agency to another is to attain “policy and program coordination.” This is clearly etched out in Section 38(3), Chapter 7, Book IV of the aforecited Code, to wit: (3) Attachment. — (a) This refers to the lateral relationship between the department or its equivalent and attached agency or corporation for purposes of policy and program coordination. The coordination may be accomplished by having the department represented in the governing board of the attached agency or corporation, either as chairman or as a member, with or without voting rights, if this is permitted by the charter; having the attached corporation or agency comply with a system of periodic reporting which shall reflect the progress of programs and projects; and having the department or its equivalent provide general policies through its representative in the board, which shall serve as the framework for the internal policies of the attached corporation or agency. the petition is granted and Resolution of the respondent Commission is hereby annulled and set aside NOTES: Section 17, Chapter 3, Subtitle A. Title I, Book V of the Administrative Code of 1987 as the source of its power to abolish the CESB. Section 17 provides: Sec. 17. Organizational Structure. — Each office of the Commission shall be headed by a Director with at least one Assistant Director, and may have such divisions as are necessary independent constitutional body, the Commission may effect changes in the organization as the need arises. Sec. 16. Offices in the Commission. — The Commission shall have the following offices: 7. Luzon Development Bank v. Association of Luzon Development Bank Employees FACTS: From a submission agreement of the LDB and the Association of Luzon Development Bank Employees (ALDBE) arose an arbitration case to resolve the following issue: Whether or not the company has violated the CBA provision and the MOA on promotion. At a conference, the parties agreed on the submission of their respective Position Papers. Atty. Garcia, in her capacity as Voluntary Arbitrator, received ALDBE’s Position Paper ; LDB, on the other hand, failed to submit its Position Paper despite a letter from the Voluntary Arbitrator reminding them to do so. As of May 23, 1995 no Position Paper had been filed by LDB. Without LDB’s Position Paper, the Voluntary Arbitrator rendered a decision disposing as follows: WHEREFORE, finding is hereby made that the Bank has not adhered to the CBA provision nor the MOA on promotion. Hence, this petition for certiorari and prohibition seeking to set aside the decision of the Voluntary Arbitrator and to prohibit her from enforcing the same. ISSUE: WON a voluntary arbiter’s decision is appealable to the CA and not the SC HELD: the Court resolved to REFER this case to the Court of Appeals. YES

The jurisdiction conferred by law on a voluntary arbitrator or a panel of such arbitrators is quite limited compared to the original jurisdiction of the labor arbiter and the appellate jurisdiction of the NLRC for that matter. The “(d)ecision, awards, or orders of the Labor Arbiter are final and executory unless appealed to the Commission …” Hence, while there is an express mode of appeal from the decision of a labor arbiter, Republic Act No. 6715 is silent with respect to an appeal from the decision of a voluntary arbitrator. Yet, past practice shows that a decision or award of a voluntary arbitrator is, more often than not, elevated to the SC itself on a petition for certiorari, in effect equating the voluntary arbitrator with the NLRC or the CA. In the view of the Court, this is illogical and imposes an unnecessary burden upon it. In Volkschel Labor Union, et al. v. NLRC, et al., 8 on the settled premise that the judgments of courts and awards of quasi-judicial agencies must become final at some definite time, this Court ruled that the awards of voluntary arbitrators determine the rights of parties; hence, their decisions have the same legal effect as judgments of a court. In Oceanic Bic Division (FFW), et al. v. Romero, et al., this Court ruled that “a voluntary arbitrator by the nature of her functions acts in a quasi-judicial capacity.” Under these rulings, it follows that the voluntary arbitrator, whether acting solely or in a panel, enjoys in law the status of a quasi-judicial agency but independent of, and apart from, the NLRC since his decisions are not appealable to the latter. Section 9 of B.P. Blg. 129, as amended by Republic Act No. 7902, provides that the Court of Appeals shall exercise: (B) Exclusive appellate jurisdiction over all final judgments, decisions, resolutions, orders or awards of RTC s and quasi-judicial agencies, instrumentalities, boards or commissions, including the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Employees Compensation Commission and the Civil Service Commission, except those falling within the appellate jurisdiction of the Supreme Court in accordance with the Constitution, the Labor Code of the Philippines under Presidential Decree No. 442, as amended, the provisions of this Act, and of subparagraph (1) of the third paragraph and subparagraph (4) of the fourth paragraph of Section 17 of the Judiciary Act of 1948. Assuming arguendo that the voluntary arbitrator or the panel of voluntary arbitrators may not strictly be considered as a quasi-judicial agency, board or commission, still both he and the panel are comprehended within the concept of a “quasi-judicial instrumentality.” An “instrumentality” is anything used as a means or agency. Thus, the terms governmental “agency” or “instrumentality” are synonymous in the sense that either of them is a means by which a government acts, or by which a certain government act or function is performed. The word “instrumentality,” with respect to a state, contemplates an authority to which the state delegates governmental power for the performance of a state function. An individual person, like an administrator or executor, is a judicial instrumentality in the settling of an estate, in the same manner that a sub-agent appointed by a bankruptcy court is an instrumentality of the court, and a trustee in bankruptcy of a defunct corporation is an instrumentality of the state. The voluntary arbitrator no less performs a state function pursuant to a governmental power delegated to him under the provisions therefor...

Similar Free PDFs

Cruz Administrative Law Reviewer

- 11 Pages

Administrative Law - Lecture notes 1

- 48 Pages

Administrative Law - Admin Law

- 6 Pages

Administrative Law Outline

- 33 Pages

Administrative Law - Essay

- 5 Pages

Administrative law (4th)

- 59 Pages

Administrative Law Outline / Summary

- 46 Pages

Administrative LAW MERITS REVIEW

- 38 Pages

Administrative Law Outline

- 14 Pages

Administrative Law 70617 - Essay

- 14 Pages

Administrative law Notes Kenya

- 10 Pages

Popular Institutions

- Tinajero National High School - Annex

- Politeknik Caltex Riau

- Yokohama City University

- SGT University

- University of Al-Qadisiyah

- Divine Word College of Vigan

- Techniek College Rotterdam

- Universidade de Santiago

- Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Johor Kampus Pasir Gudang

- Poltekkes Kemenkes Yogyakarta

- Baguio City National High School

- Colegio san marcos

- preparatoria uno

- Centro de Bachillerato Tecnológico Industrial y de Servicios No. 107

- Dalian Maritime University

- Quang Trung Secondary School

- Colegio Tecnológico en Informática

- Corporación Regional de Educación Superior

- Grupo CEDVA

- Dar Al Uloom University

- Centro de Estudios Preuniversitarios de la Universidad Nacional de Ingeniería

- 上智大学

- Aakash International School, Nuna Majara

- San Felipe Neri Catholic School

- Kang Chiao International School - New Taipei City

- Misamis Occidental National High School

- Institución Educativa Escuela Normal Juan Ladrilleros

- Kolehiyo ng Pantukan

- Batanes State College

- Instituto Continental

- Sekolah Menengah Kejuruan Kesehatan Kaltara (Tarakan)

- Colegio de La Inmaculada Concepcion - Cebu