Exam 17 November 2010, questions PDF

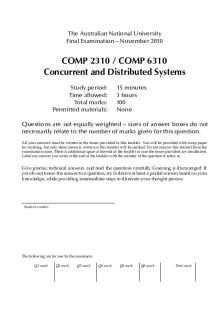

| Title | Exam 17 November 2010, questions |

|---|---|

| Course | Company law |

| Institution | University of London |

| Pages | 4 |

| File Size | 231.7 KB |

| File Type | |

| Total Downloads | 140 |

| Total Views | 858 |

Summary

LIFTING THE VEIL May 2017 Zone B Question 5 Porterhead plc is a large company, carrying on a number of different businesses. Until 2015, one of these businesses involved making batteries for mobile telephones. In 2015, Porterhead sold this battery-making business to Batteries plc. In the contract fo...

Description

LIFTING THE VEIL May 2017 Zone B Question 5 Porterhead plc is a large company, carrying on a number of different businesses. Until 2015, one of these businesses involved making batteries for mobile telephones. In 2015, Porterhead sold this battery-making business to Batteries plc. In the contract for the sale of the business to Batteries plc, Porterhead agreed not to make batteries for a period of five years. In 2016, Porterhead decided it wanted to start making batteries again. However, to get around the restriction in the contract with Batteries plc, it arranged for one of its subsidiary companies, Selltech Ltd, to make the batteries. Porterhead had formed Selltech many years earlier. Selltech began making the batteries in a small factory in London. Immediately, there were problems with chemical leaks from the factory. The directors of Porterhead were not told about these problems. In March 2017, due to Selltech’s negligence, a large leak of chemicals from the factory injured Mary, an employee of Selltech, and Noris, a neighbour of Selltech’s factory. The directors of Selltech have told Mary and Noris that Selltech has no money to compensate them for their injuries. a) Advise Batteries whether it could take any action against either Porterhead or Selltech to enforce Porterhead’s promise not to make batteries; and b) Advise both Mary and Noris whether they could bring a claim againstPorterhead in respect of the injuries they have suffered.

1

Answer In regards to part (a), it relates to corporate personality and whether Batteries plc (B, hereafter) could take any action against Porterhead plc (P, hereafter) or Selltech (S, hereafter) to enforce P’s promise not to make batteries. B needs to be noted that according to Salomon v Salomon & Co and the law of company, the moment a company is formed it becomes a separate legal entity, with its own rights and liabilities. It can sue and be sued. It can own property. Thus the liability of the member is limited only to their initial investment, in case the company goes into liquidation. The principle of Salomon and the doctrine of corporate personality was followed and confirmed in the subsequent cases of Lee v Lees Air Farming and Macaura v Northern Assurance. This principle applies also to group companies as well – Adams v Cape; Woolfson v SRC . Thus, P and Selltech are separate legal entities and either P or S will not be held liable for any losses or liabilities incurred by the subsidiary, S (Re Southward). As such, B plc is advised that they cannot enforce P’s promise since it was S, P’s subsidiary, that made the batteries. As such, B plc would want to rely on corporate veil lifting against P as it applies as an exception to Salomon principle. B plc is advised that English courts are very protective of the Salomon principle. It is very difficult for them to pierce the corporate veil in normal circumstances. But at times, in certain just conditions the veil is lifted. Whether or not the can be lifted between P for S; misdemeanor, resulting to a large leak of chemicals injuring both an employee, Mary, and a neighbor Noris, needs to be evaluated by unraveling a number of case laws that evolved throughout the years. As considered there are two types of veil lifting namely, statutory and common law veil lifting. In considering common law veil lifting, it is submitted that the notion of corporative personality was upheld by Salomon principle until 1996 as the House of Lords (HOL, hereafter) could not overrule itself during the this period. However, veil lifting did occur in exceptional circumstances during this period. It was the case of Daimler Co Ltd where the court lifted the veil of incorporation for the first time on the grounds of national security. The above, however, was a starter of the growing concept of veil lifting. In both Gilford Motors Co Ltd v Horne and Jones v Lipman the court lifted the veil since both of the wrongdoers purposefully set up a company and transferred the assets to the company so as to evade existing legal obligation. By 1969, Lord Denning seemed to be on a crusade to encourage veil lifting. In the case of Littlewoods Mail Order Store, Lord Denning indicated that law required change and stated that whenever justice would demand the veil must be lifted. Lord Denning 2

further proposed in DHN Ltd v Tower Hamlet that a group of companies must always be treated as a single economic unit. However, this decision was hugely criticized and two years later, the HL in Woolfson specifically disapproved Denning’s view on group stricture in finding the veil of incorporation would be upheld unless it was a mere façade. Although Re A Company drawing on Wallersteiner supported the principle of Littlewoods, but the Court of Appeal (CA, hereafter) in National Dock Labour Board Ltd moved finally against a more interventionist approach where group structure were concerned. According to Lowry and Dignam, the above uncertainty has been redressed by the CA in Adams V Cape Industries plc, which effectively laid down the possibility of veil lifting to only 3 situations. Firstly, where there is any statute or document indicating that P plc and Selltech are to be treated as a single economic entity – DHN v Tower Hamlets. On the facts, there is no suggestion of any such expression mention P and S are to be treated as a single economic unit. Neither, is there any mention of lack of clarity of a statute or document that would allow the court to interpret and to treat this group as a single entity – Hall. Secondly, whether there is an agency agreement. Nothing in the fact suggest of any evidence of express agreement inclusive in the company article or any possibility of an implied agency agreement as Adams makes it clear there has to be day control by P over S; Miriam v The Print Factory. Lastly, the court may lift the veil of incorporation where the company is a mere façade. There is nothing in the fact to suggest that S was located in a different country so as to minimize tax and other liabilities as seen in Adams. However, the only justified reason for the S formation is that P wanted to start making batteries which is clearly the breach of their agreement with B. In Adams and Prest, the court considered the fact of whether there is a pre-existing legal obligation or liability, which existed before the formation of the company in order to lift the veil. B is advised that following VTB v Nutritek, since the parties to the contract are P and, only they are privy to the contract, which can enforce their rights and obligations against each other. There is no reason for the court to lift the veil to make S a party to the contract and thus the principle of privity of contract is upheld. As such, B is advised that since it was S which made the batteries, P did not breach its promise unless B can prove S is a mere façade. On the facts, P had formed S many years ago. Following cases like Smallbone v Trustor and Raja v Van Hoogstraten, the company having been originally formed for legitimate purpose does not prevent it from being a façade subsequently. Clearly there are pre-existing legal obligations on the part of P not to make batteries and by arranging to make batteries instead through S, P is using S to frustrate B’s legal right to enforce against P – Prest, Adams. A further pointed should be noted that the legislative intervention would not apply here, as there is no course of winding up of P.

3

In regards to part (b), it was established that a parent company, P could owe a duty of to Mary, an employee of S, or Noris, a neighbor of S depending on the amount of control over the subsidiary company, S as seen in Connelly. The case of Lubbe v Cape Industries plc continued the pattern of lifting the veil where tortious liability for person is at issue. Applying the guidance of Chandler, such a duty of care is likely to be imposed in 4 situations. First, where the businesses of the parent and subsidiary are in a relevant respects the same. On the fact it can be seen both P and S are manufacturing. Second, the parent has or should have superior knowledge of some relevant aspect of the particular industry or product. Indeed, it has been seen that P was making batteries before S, which indicates that P has the superior knowledge. Thirdly, the subsidiary's system of work was unsafe or was likely to cause harm, as the parent company knew or should have known. The fact doesn’t show any such indication; thereby there might be an assumption of responsibility. Fourthly, the parent knew or should have foreseen that the subsidiary, its employees or consumers would rely on its using that superior knowledge for employees' or consumers' protection. Likewise the last point, the assumption of responsibility by P over health and safety policy of S created a relationship between the employee and the parent company, which give rise to a duty of care. The duty, which on the face of the facts seems to breached by P and hence might be liable to pay damages for injuries suffered by the employee, Mary. It should be noted that Chandler itself focuses on duty to employees, but Lungowe suggests others, including in this scenario, Noris, might also be able to claim a duty of care owed to him. However, Thompson and Okpabi both suggest there will be no duty where the parent company is a ‘pure holding company’, not itself engaged directly in the industry in which its subsidiary has operated. Holding company is a corporation that owns enough voting stock in one or more other companies to exercise control over them. A corporation that exists solely for this purpose is called a pure holding company, while one that also engages in a business of its own is called a holding-operating company. Therefore, it is not quite clear whether P is an pure holding company or an holding operating company.

4...

Similar Free PDFs

Exam 17 November 2010, questions

- 4 Pages

Exam November 2017, questions

- 8 Pages

Exam November 2014, questions

- 21 Pages

Exam November, questions

- 3 Pages

Exam November 2016, questions

- 10 Pages

Exam 16 November, questions

- 2 Pages

Exam November 2017, questions

- 4 Pages

Exam November 2019, questions

- 8 Pages

Exam November 2017, questions

- 6 Pages

Exam 2010, questions

- 2 Pages

Exam 2010-2014, questions

- 6 Pages

Exam 2010, questions

- 20 Pages

Exam June 2010, questions

- 10 Pages

Exam 12 November 2018, questions

- 12 Pages

Exam 2010, questions

- 25 Pages

Popular Institutions

- Tinajero National High School - Annex

- Politeknik Caltex Riau

- Yokohama City University

- SGT University

- University of Al-Qadisiyah

- Divine Word College of Vigan

- Techniek College Rotterdam

- Universidade de Santiago

- Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Johor Kampus Pasir Gudang

- Poltekkes Kemenkes Yogyakarta

- Baguio City National High School

- Colegio san marcos

- preparatoria uno

- Centro de Bachillerato Tecnológico Industrial y de Servicios No. 107

- Dalian Maritime University

- Quang Trung Secondary School

- Colegio Tecnológico en Informática

- Corporación Regional de Educación Superior

- Grupo CEDVA

- Dar Al Uloom University

- Centro de Estudios Preuniversitarios de la Universidad Nacional de Ingeniería

- 上智大学

- Aakash International School, Nuna Majara

- San Felipe Neri Catholic School

- Kang Chiao International School - New Taipei City

- Misamis Occidental National High School

- Institución Educativa Escuela Normal Juan Ladrilleros

- Kolehiyo ng Pantukan

- Batanes State College

- Instituto Continental

- Sekolah Menengah Kejuruan Kesehatan Kaltara (Tarakan)

- Colegio de La Inmaculada Concepcion - Cebu