LAWS1160 PDF

| Title | LAWS1160 |

|---|---|

| Author | Daniella Burt |

| Course | Administrative Law |

| Institution | University of New South Wales |

| Pages | 6 |

| File Size | 196.9 KB |

| File Type | |

| Total Views | 118 |

Summary

LAWS1160 Notes...

Description

1

UNSW Law

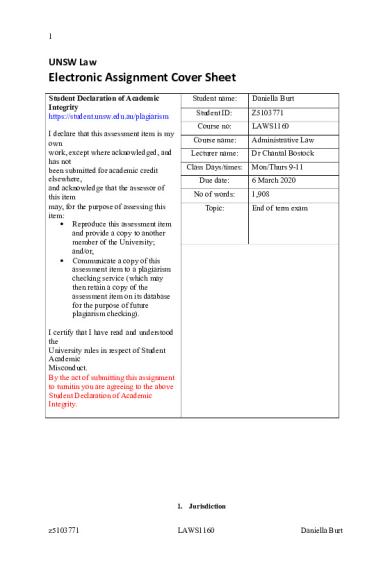

Electronic Assignment Cover Sheet Student Declaration of Academic Integrity https://student.unsw.edu.au/plagiarism I declare that this assessment item is my own work, except where acknowledged, and has not been submitted for academic credit elsewhere, and acknowledge that the assessor of this item may, for the purpose of assessing this item: Reproduce this assessment item and provide a copy to another member of the University; and/or, Communicate a copy of this assessment item to a plagiarism checking service (which may then retain a copy of the assessment item on its database for the purpose of future plagiarism checking).

Student name:

Daniella Burt

Student ID:

Z5103771

Course no:

LAWS1160

Course name:

Administrative Law

Lecturer name:

Dr Chantal Bostock

Class Days/times: Due date: No of words: Topic:

Mon/Thurs 9-11 6 March 2020 1,908 End of term exam

I certify that I have read and understood the University rules in respect of Student Academic Misconduct. By the act of submitting this assignment to turnitin you are agreeing to the above Student Declaration of Academic Integrity.

1. Jurisdiction

z5103771

LAWS1160

Daniella Burt

2 The Public Health (Emergency Powers) Act 2011 (Cth) (Health Act) is a Commonwealth act and may be reviewed in the Federal Court.1 Review in this court is preferred, as if error is found YoPro will potentially have access to remedies under both the Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth)(ADJR Act)2 and the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth).3

2. Commencing Action a. Standing? The Health Act does not contain any requirements for parties standing. At common law, YoPro would need to demonstrate a special interest in the decision. 4 Though YoPro has philosophical interests5 in spreading the benefits of barre and related exercises that may not be classed as sufficient for standing, they also operates as a members studio that relies on fees of those members to advertise and generate revenue, and has a genuine financial interest in the decision. To continue to prohibit the practice of barre would adversely affect these interests.6

b. Justiciable matter? The COBIS-19 (Closure of Certain Businesses) Order (Order) was made by Dr Goose as the Chief Health Officer under the Health Minister of the Commonwealth, as authorised under the Health Act. 7 Prohibiting barre practice is substantive and final8 decision on a real (non-hypothetical) matter9 concerning a controversy10 about the right of YoPro to practice barre in their studio, and is therefore justiciable 3. Grounds of review a. Acting without power i.

Was section 12 prerequisite met?

The CHO may have been acting without authority. The Governor General did not declare the state of emergency on the advice of the CHO as required11 by statute. The CHO only has jurisdiction to give orders in the event of a state of emergency, 12 and if this was not correctly declared there has been a

1 Se c t i on39 B( 1 )J u di c i a r yAc t1 903( Ct h ) . 2 Se c t i on16Admi ni s t r a t i v eDe c i s i ons( J ud i c i alRe v i e w)Ac t19 77( Ct h) . 3 Se c t i on39 B( 1 A)J ud i c i ar yAc t 190 3( Ct h) . 4 Au s t r al i anCon s e r v a t i onFo und at i onI n cvCommon we al t h( 19 80)14 6CLR49 3. 5 Ri g htt oLi f eAs s o c i a t i on( NSW)I ncvS e c r e t ar y ,De pa r t me ntof HumanS e r v i c e san dHe al t h( 19 95 )56FCR 50 ;37ALD35 7,1 28ALR. 6 Se c t i on3( 4 )Admi ni s t r at i v eDe c i s i on s( J u di c i a lRe v i e w)Ac t1 977( Ct h) . 7 Ta n gvMi n i s t e rf orI mmi g r a t i ona ndEt h ni cAffai r s( 19 86)67ALR17 7. 8 Bo ndvTheQue e n( 2 00 0)2 01CLR213 . 9 Mc Bai n , Re :Expa r t eAus t r al i a nCa t h ol i cBi s h opsCon f e r e n c e( 200 2)209CLR372 . 10 I bi d , ReJ udi c i ar ya ndNav i g at i onAc t s( 19 21 )29CLR257 . 11 Section 12(1) Public Health (Emergency Powers) Act 2011 (Cth). 12 Section 13(1) Public Health (Emergency Powers) Act 2011 (Cth).

z5103771

LAWS1160

Daniella Burt

3 prerequisite procedure in the statute that has not been met, giving rise to a ground of review under section 5(1)(b) of the ADJR Act.

ii.

Did CHO have authority?

As the declaration procedure was not observed, this may mean that the CHO never had the authority to make the decision to prohibit barre from the beginning.

iii.

Remedies?

Acting without power is a jurisdictional error. This impacts the remedies available in two main manners. First, if a court is to find that the CHO was acting without power, it would render the decision void ab initio. Generally, jurisdictional errors such as acting without power are ruled to be a nullity as they are considered ‘not decisions at all’.13 Decisions that are void ab initio also preclude the effectiveness of any privative clauses14, as found in Part 6.15 Second, as a jurisdictional error, remedy can be attained through both section 75(v) of the Constitution and section 16 of the ADJR Act. In this case, the ADJR Act is just as useful and generally more liberal in application, therefore preferable for YoPro to apply under it. Because acting without power is viewed as void ab initio, it would be unnecessary for YoPro to ask the court to quash the CHO’s decision.16 An order referring the matter back to the CHO for consideration is available17 and likely to be satisfactory as the reconsideration can be subject to any directions that the court sees fit.18 This might include instructing the CHO to consider the information provided to her in the email from YoPro.

iv.

Success?

There may be some reluctance on behalf of the court to void the decision in its entirety in the context of the pandemic, however it is still likely that the court would find a jurisdictional error. The CHO has acted without power and this is made clear in the facts that the prerequisites to her obtaining jurisdiction to make the decision were not met.

b. Improper use of power If a court finds that the CHO has acted within her power, YoPro may still apply for a review on an improper exercise of power.19 13 Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs v Bhardwaj [2002] HCA 11. 14 Anisminic Ltd v Foreign Compensation Commission [1969] 2 AC 147. 15 Public Health (Emergency Powers) Act 2011 (Cth). 16 Section 16(1)(a) Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth). 17 Section 16(1)(b) Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth). 18 Ibid. 19 Section 5(1)(e)Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth).

z5103771

LAWS1160

Daniella Burt

4

i.

Direction of another person

Improper use of power includes any decisions that are made by a decision maker at the behest of another person.20 Before announcing her Order, the CHO is instructed by the Health Minister to take much stricter measures and ban all non-essential interactions, and it is clear that the measures that were announced in the CHO’s COBIS-20 Order were not entirely her own. She is not basing the decision on the evidence available to her; she is aware that the most important thing is to stop people touching one another and being near Ibis birds but still makes an order to ban all non-essential activities. She herself even notes that the policy might be regarded by some as ‘overreach’ as it is understood that the virus does not spread through the air. An explanation as to why she chose these measures is because they were dictated to her by the Minister. It then follows that the decision to prohibit barre is not from her own reasoning, but that of the Order as created at the behest of the Minister. In principle it is not objectionable that a Minister take steps to encourage matching administrative decisions with policy views held by the government, 21 but the official responsible for the decision should be on face the one who makes the decision.

ii.

Policy fettering discretion

Improper use of power can also include an exercise of discretionary power in accordance with a rule or policy but without regard to the merits of the particular case. 22 Power must be exercised in light of the individual circumstances at the time. This goes in hand with the decision maker acting at the behest of another person. When the CHO decided to prohibit barre studios, she noted that she classified it as both an exercise facility and a dance hall, the latter of which was prohibited under the COBIS-20 Order. Decision makers must be willing to make exceptions within the policy if it is justified in the circumstances. In this case, the CHO did not listen to YoPro’s email detailing the particulars of barre as an exercise. The fact that barre in practice does not offer any avenue for the virus to spread is justification to create an exception to allow barre to be practiced in their studio. The CHO’s application of the Order is inflexible in this regard.

iii.

Unreasonableness

A power is improperly exercised if it is deemed to be unreasonable.23 This test has a significantly high threshold,24 with decisions only being deemed unreasonable if they are so that “no reasonable authority could ever come to it.” 25 Unreasonableness can also be inferred where a decision appears to

20 Section 5(2)(e)Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth). 21 R v Anderson; Ex parte Ipec-Air Pty Ltd (1965) 113 CLR 177; [1965] ALR 1067. 22 Section 5(1)(f)Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth). 23 Section 5(2)(g) Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth). 24 Associated Provincial Picture Houses Ltd v Wednesbury Corporation (1948) 1 KB 223. 25 Ibid.

z5103771

LAWS1160

Daniella Burt

5 be arbitrary, capricious, without common sense or ‘plainly unjust’. 26 It can be inferred that the CHO as a registered health practitioner knows how to access information that is reliable and based in fact. It cannot be said that she has informed her decision this way, but instead capriciously on what a google search told her. It does not follow common sense that she would agree that pilates and yoga are acceptable exercises because they do not require close contact, but then prohibit the exercise that is essentially a combination of these two. If the CHO’s line of logic is to be followed, barre should be permitted. But this is not the case. Because permitting barre practice is still in keeping with the CHO’s line of logic, it is arguable that the courts would not be substituting their own idea of ‘reasonable’ on her behalf. 27

iv.

Remedies?

Improper use of power is a non-jurisdictional error, so only ADJR Act remedies are available to YoPro. This will mean the remedies needed to secure the most favourable outcome will be different than the those in a(iii). Because the decision is not regarded as invalid from the beginning, YoPro should request the court firstly quash the CHO’s decision to prohibit barre.28 Because of this, the best remedies to secure a favourable outcome for YoPro would be to request the court firstly quash the CHO’s decision to prohibit barre,29 and request that the court remit the matter back to the CHO for consideration subject to any directions that the court sees fit.30 However, the privative clause in Part 6 of the Health Act may present a problem for this ground. It may oust certiorari because it is a non-constitutional remedy. 31 Nevertheless, there is no general rule to the meaning of privative clauses32 and courts do have ample room to ignore or interpret them even if they are not constitutionally invalidated.33 There is tension with privative clauses and courts as to ensure parliamentary supremacy,34 but it is arguable that the denial of any avenue for review, as is the case here, is not a bona fide 35 attempt at protecting the decisions made by CHO, and a court would likely disregard it. So, it is likely that a certiorari remedy would not be barred. YoPro could then seek that the matter be remitted to the CHO for consideration subject to any directions that the court sees fit.

v.

Prospects of success?

26 Minister for Immigration & Citizenship v Li (2013) 249 CLR 332, [28]; Singh v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs (2001) 109 FCR 152, [44]. 27 Minister for Immigration & Citizenship v Li (2013) 249 CLR 332. 28 Section 16(1)(a) Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth). 29 Section 16(1)(a) Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth). 30 Ibid. 31 R v Hickman; Ex parte Fox and Clinton (1945) 70 CLR 598. 32 Plaintiff s157/2002 v Commonwealth (2003) 195 ALR 24. 33 Ibid 34 Osmond v Public Service Board of New South Wales [1984] 3 NSWLR 447. 35 Administrative Review Committee, ‘Report of the Commonwealth Administrative Review Committee’ (1971), [55].

z5103771

LAWS1160

Daniella Burt

6 Compared with the grounds for acting without power, the arguments for this ground may be slightly less compelling. The arguments for acting without power are on face more straightforward than the arguments presented here. However, as mentioned, because the context of the decision, a court might be more preferable to this outcome as it upholds the parts of the Order that are not relevant to this case but allows remedy for YoPro’s matter specifically. This is the less invasive option for the court.

z5103771

LAWS1160

Daniella Burt...

Similar Free PDFs

LAWS1160

- 6 Pages

Popular Institutions

- Tinajero National High School - Annex

- Politeknik Caltex Riau

- Yokohama City University

- SGT University

- University of Al-Qadisiyah

- Divine Word College of Vigan

- Techniek College Rotterdam

- Universidade de Santiago

- Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Johor Kampus Pasir Gudang

- Poltekkes Kemenkes Yogyakarta

- Baguio City National High School

- Colegio san marcos

- preparatoria uno

- Centro de Bachillerato Tecnológico Industrial y de Servicios No. 107

- Dalian Maritime University

- Quang Trung Secondary School

- Colegio Tecnológico en Informática

- Corporación Regional de Educación Superior

- Grupo CEDVA

- Dar Al Uloom University

- Centro de Estudios Preuniversitarios de la Universidad Nacional de Ingeniería

- 上智大学

- Aakash International School, Nuna Majara

- San Felipe Neri Catholic School

- Kang Chiao International School - New Taipei City

- Misamis Occidental National High School

- Institución Educativa Escuela Normal Juan Ladrilleros

- Kolehiyo ng Pantukan

- Batanes State College

- Instituto Continental

- Sekolah Menengah Kejuruan Kesehatan Kaltara (Tarakan)

- Colegio de La Inmaculada Concepcion - Cebu