Lesson 13 Long Run Equilibrium PDF

| Title | Lesson 13 Long Run Equilibrium |

|---|---|

| Author | Harsh Drolia |

| Course | ECONOMICS |

| Institution | The University of Texas at Arlington |

| Pages | 13 |

| File Size | 579.3 KB |

| File Type | |

| Total Downloads | 73 |

| Total Views | 119 |

Summary

Economics Jane Himarios...

Description

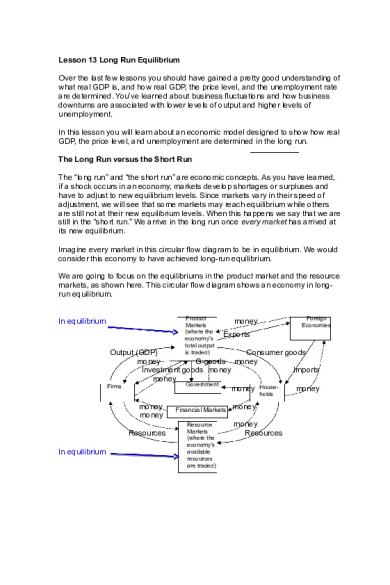

Lesson 13 Long Run Equilibrium Over the last few lessons you should have gained a pretty good understanding of what real GDP is, and how real GDP, the price level, and the unemployment rate are determined. You’ve learned about business fluctuations and how business downturns are associated with lower levels of output and higher levels of unemployment. In this lesson you will learn about an economic model designed to show how real GDP, the price level, and unemployment are determined in the long run. The Long Run versus the Short Run The “long run” and “the short run” are economic concepts. As you have learned, if a shock occurs in an economy, markets develop shortages or surpluses and have to adjust to new equilibrium levels. Since markets vary in their speed of adjustment, we will see that some markets may reach equilibrium while others are still not at their new equilibrium levels. When this happens we say that we are still in the “short run.” We arrive in the long run once every market has arrived at its new equilibrium. Imagine every market in this circular flow diagram to be in equilibrium. We would consider this economy to have achieved long-run equilibrium. We are going to focus on the equilibriums in the product market and the resource markets, as shown here. This circular flow diagram shows an economy in longrun equilibrium. Product Markets (where the economy’s total output is traded)

In equilibrium

Foreign Economies

money Exports

Output (GDP) Consumer goods money G-goods money Investment goods money Imports money Government Firms money Housemoney holds

money money Resources In equilibrium

Financial Markets money Resource Markets (where the economy’s available resources are traded)

money Resources

Now imagine that something happens to knock one of these markets out of equilibrium. Since markets are inter-connected, eventually many or even all markets will have to adjust and find their new equilibrium. It is possible that “the product market,” for example, might find its new equilibrium before “the resource market” does. In this case we would say that the economy is in short-run equilibrium and that the product market has achieved short-run equilibrium. Product Markets (where the economy’s total output is traded)

In equilibrium again

money

Foreign Economies

Exports

Output (GDP) Consumer goods money G-goods money Investment goods money Imports money Government Firms money Housemoney holds

money money Resources Not yet in equilibrium

Financial Markets money Resource Markets (where the economy’s available resources are traded)

money Resources

This economy will only achieve its new long-run equilibrium when all the markets find their new resting place. Product Markets (where the economy’s total output is traded)

In equilibrium again

money

Foreign Economies

Exports

Output (GDP) Consumer goods money G-goods money Investment goods money Imports money Government Firms money Housemoney holds

money money Resources In equilibrium again

Financial Markets money Resource Markets (where the economy’s available resources are traded)

money Resources

The long-run and short-run aren’t defined by time intervals like a year or a month. Instead they are defined by whether all or only some markets have returned to equilibrium once a shock occurs. As I wrote above, in this lesson you will learn about an economic model designed to show how real GDP, the price level, and unemployment are determined in the long run. Important things to remember about this: 1. Since we are talking about the long run, once a shock occurred, every market has returned to equilibrium. 2. Real GDP and the price level are determined in the product market. 3. Employment levels are determined in the resource market. Since unemployment = a surplus of labor, any unemployment above the natural rate of unemployment indicates that the resource market is in disequilibrium and therefore that the economy is not experiencing long run equilibrium. Therefore, if we say we are in long run equilibrium, we know the unemployment rate = its natural rate.

Output Growth and the Long-Run Aggregate Supply Curve LRAS is a vertical line representing the real output of goods and services after full adjustment has occurred. When we are on the LRAS, real GDP is at its potential. (We achieve real GDPpotential.) LRAS represents the real GDP of the economy under conditions of full employment.

Another way to examine long run equilibrium is to draw the product market graph above the resource market graph (this mimics their locations on the circular flow diagram). We will use “the labor market” as a stand-in for all the “resource markets” since we want to talk about unemployment. LRAS Price Level In equilibrium Product Market

Wage rate Also “in equilibrium”

RealGDP* Supply of Labor Labor Market as a proxy for the Resource Market Demand for Labor L*

Notice that both markets are in equilibrium so this is a long-run equilibrium situation. L* is the equilibrium quantity of labor. Generally we think of equilibrium as meaning that no unemployment (surplus) exists. But in this case, when we are at L* the unemployment rate equals the natural rate of unemployment. This is kind of bizarre, right? But it corresponds to the point where on the top graph where Real GDP* = Real GDPpotential.

Growth:

Every point on the first LRAS curve represents a combination of capital and consumption goods worth $17.3 trillion. As the economy grows, we show the growth by shifting the LRAS curve rightward. Every point on the new LRAS curve represents a combination of capital and consumption goods worth $18 trillion.

Notice that the price level (vertical axis) does not affect what we are capable of producing in the long run. Our production capability is determined by our resources, technology, and institutions (the things we studied in the previous lesson).

Total Expenditures and Aggregate Demand Aggregate Demand is the total of all planned expenditures in the entire economy. It is the quantity of real GDP demanded by households, businesses, government, and foreigners at different price levels, ceteris paribus The AD curve shows planned purchase rates for all final goods and services in the economy at various price levels, all other things held constant.

Remember from chapter 7 that the GDP deflator is a price index. We will use the GDP deflator as an estimate of the actual price level.

Moving Along an Existing AD Curve There is an inverse relationship between the price level and the quantity of real GDP demanded, ceteris paribus. Economists believe that there are three effects that work simultaneously to cause this inverse relationship. They are: 1.

The Real-Balance (or Wealth) Effect

A price level change affects the value of fixed financial assets. When the price level rises, dollar-denominated assets such as savings accounts and bonds are devalued (the real purchasing power of these assets falls). This change leads people to spend less because they aren’t as wealthy as they were before the price level changed. 2. The Open Economy Effect: Substitution of Imports for Domestic Goods A price level change affects relative world prices. As the price level rises, American goods become more expensive relative to foreign goods, so exports decrease and imports increase. Since EX and IM are components of AD, we see a movement up to the left along the existing AD curve. 3.

Interest Rate Effect

A price level change affects interest rates. As the price level rises people will need to hold more dollars just to make their ordinary purchases: they demand more dollars and this drives up interest rates. At higher interest rates, consumers and firms borrow less and therefore C and I spending falls. Since C and I are components of AD, we see a movement up to the left along the existing AD curve.

Shifting to a New AD Curve Aggregate Demand Curve Shifters

An increase in AD is shown by shifting the AD curve rightward, and a decrease in AD is shown by shifting the AD curve leftward. If you’ve forgotten what is being measured on the vertical and horizontal axes, see the previous page.

AD1 AD2

An increase in AD

AD2

A decrease in AD

AD1

Long-Run Equilibrium and the Price Level In the long run, the price level is determined by the intersection of LRAS and AD.

In this figure from your text, the equilibrium price level is 120 and the equilibrium level of real GDP (per year) is $18 trillion. If we are at this equilibrium point, planned spending = actual spending = $18 trillion. The AD curve shows planned spending but sometimes plans don’t work out. If plans don’t work out, here is what will happen: At a price level of 140 the AD curve shows that planned spending = $17 trillion while real GDP = $18 trillion. $1 trillion worth of goods do not get purchased, but pile up in inventories. Essentially there is $1 trillion worth of unplanned inventory investment (to use a term from an earlier lesson). Since firms are trying to sell more than customers want to buy, the surplus pushes the price level down towards 120. At a price level of 100 the AD curve shows that planned spending = $19 trillion while real GDP = $18 trillion. Customers are trying to buy $1 trillion more goods than firms are currently producing. Let’s assume that firms have inventory from past years on hand just in case they face this situation. Essentially there is an unplanned inventory disinvestment of $1 trillion. And since customers are trying to buy more than producers are currently producing, the shortage pushes the price level will up towards 120. Conclusion: If we aren’t in equilibrium at real GDPpotential, we will get there eventually, as the price level adjusts.

Moving From One Point of Long-Run Equilibrium to Another Four Simple Cases: 1. If AD increases, the price level will rise while real GDP will stay at its potential. This is known as demand-pull inflation. Your text shows this in Figure 10-8, Panel (b):

2. If AD decreases, the price level will fall while real GDP will stay at its potential. Deflation occurs. This isn’t shown in your text but looks like this: LRAS Price Level P1 P2 AD2 AD1 RealGDPpotential = RealGDP1 = RealGDP2

3. If LRAS increases (economic growth occurs), the price level will fall and real GDPpotential will rise. This is sometimes called secular deflation. Your text shows this in Figure 10-6, Panel (a):

4. If LRAS decreases (this doesn’t usually happen but did with China during the Great Leap Forward and with North Korea after the Korean War), the price level will rise and real GDPpotential will fall. This is one cause of supply-side inflation. Your text shows this in Figure 10-8, Panel (a):

Economic Growth in the Real World Although we sometimes see secular deflation, economic growth is usually matched by increases in planned spending (the LRAS and AD curves shift rightward more or less together). If this happens the price level stays relatively stable while real GDPpotential rises. Your text shows this in Figure 10-6, Panel (b):

If it looks like secular deflation is occurring, the Federal Reserve (we will study this in detail later) can prevent it by increasing the money supply. Doing so will make the AD shift rightward and the price level will remain relatively stable. Here is Figure 10-6, Panel (b), again:

The only difference in these two cases is the source of the AD shift. Higher incomes caused the AD curve to shift rightward in the first case, while an increase in the money supply engineered by the Federal Reserve caused the AD curve to shift rightward in the second case. You will learn how they do this in a later lesson....

Similar Free PDFs

Lesson 13 Long Run Equilibrium

- 13 Pages

Medium-run equilibrium

- 4 Pages

Chapter 15- Long-Run Economic Growth

- 69 Pages

6. The Long-Run Economic Growth

- 9 Pages

Long term care - Long

- 4 Pages

Lesson 8 - Chapter 13 - Question

- 1 Pages

Popular Institutions

- Tinajero National High School - Annex

- Politeknik Caltex Riau

- Yokohama City University

- SGT University

- University of Al-Qadisiyah

- Divine Word College of Vigan

- Techniek College Rotterdam

- Universidade de Santiago

- Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Johor Kampus Pasir Gudang

- Poltekkes Kemenkes Yogyakarta

- Baguio City National High School

- Colegio san marcos

- preparatoria uno

- Centro de Bachillerato Tecnológico Industrial y de Servicios No. 107

- Dalian Maritime University

- Quang Trung Secondary School

- Colegio Tecnológico en Informática

- Corporación Regional de Educación Superior

- Grupo CEDVA

- Dar Al Uloom University

- Centro de Estudios Preuniversitarios de la Universidad Nacional de Ingeniería

- 上智大学

- Aakash International School, Nuna Majara

- San Felipe Neri Catholic School

- Kang Chiao International School - New Taipei City

- Misamis Occidental National High School

- Institución Educativa Escuela Normal Juan Ladrilleros

- Kolehiyo ng Pantukan

- Batanes State College

- Instituto Continental

- Sekolah Menengah Kejuruan Kesehatan Kaltara (Tarakan)

- Colegio de La Inmaculada Concepcion - Cebu