Notes - Summary Criminal Law PDF

| Title | Notes - Summary Criminal Law |

|---|---|

| Course | Criminal Law |

| Institution | Western Sydney University |

| Pages | 12 |

| File Size | 286.7 KB |

| File Type | |

| Total Downloads | 69 |

| Total Views | 142 |

Summary

notes...

Description

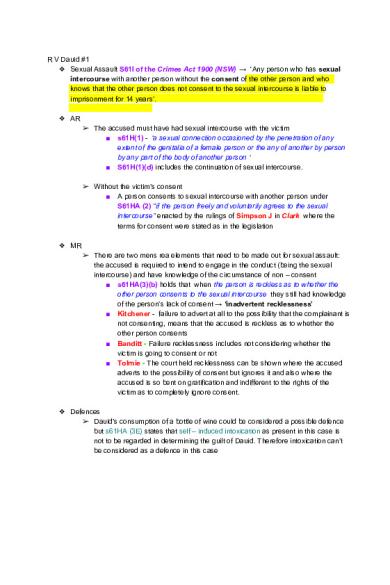

R V Dauid #1 exual ❖ Sexual Assault S61I of the Crimes Act 1900 (NSW) → ‘Any person who has s intercourse with another person without the consent of the other person and who knows that the other person does not consent to the sexual intercourse is liable to imprisonment for 14 years’. ❖ AR ➢ The accused must have had sexual intercourse with the victim ■ s61H(1) - ‘a sexual connection occasioned by the penetration of any extent of the genitalia of a female person or the any of another by person by any part of the body of another person ’ ■ S61H(1)(d) includes the continuation of sexual intercourse. ➢ Without the victim’s consent ■ A person consents to sexual intercourse with another person under S61HA (2) “if the person freely and voluntarily agrees to the sexual intercourse” enacted by the rulings of S impson J in Clark where the terms for consent were stated as in the legislation ❖ MR ➢ There are two mens rea elements that need to be made out for sexual assault: the accused is required to intend to engage in the conduct (being the sexual intercourse) and have knowledge of the circumstance of non – consent ■ s61HA(3)(b) holds that when the person is reckless as to whether the other person consents to the sexual intercourse t hey still had knowledge of the person’s lack of consent → ‘inadvertent recklessness’ ■ Kitchener - failure to advert at all to the possibility that the complainant is not consenting, means that the accused is reckless as to whether the other person consents ■ Banditt - Failure recklessness includes not considering whether the victim is going to consent or not ■ Tolmie - The court held recklessness can be shown where the accused adverts to the possibility of consent but ignores it and also where the accused is so bent on gratification and indifferent to the rights of the victim as to completely ignore consent. ❖ Defences ➢ Dauid’s consumption of a bottle of wine could be considered a possible defence but s 61HA (3E) states that self – induced intoxication as present in this case is not to be regarded in determining the guilt of Dauid. Therefore intoxication can’t be considered as a defence in this case

R V Dauid #2 ❖ S.18 of the Crimes Act 1900 (NSW) - Homicide Murder & Manslaughter AR ➢ s. 18(1)(a) Crimes Act 1900 (NSW) An act or omission causing death of a human being ❖ Murder AR ➢ Intent to kill ➢ Intent to inflict grievous bodily harm ➢ Reckless indifference to human life ➢ Royall: For murder, the prosecution has to prove that the accused foresaw the probability of death OR grievous bodily harm ❖ Involuntary Manslaughter MR ➢ Involuntary manslaughter s18(1)(b); Unlawful and dangerous act manslaughter or manslaughter by criminal negligence ➢ Royall: A defendant who is recklessly indifferent to serious bodily harm of itself will be guilty of manslaughter ➢ Wilson (1992): The circumstances must be such that a reasonable man in the accused’s position...would have realised that he was exposing another or others to an appreciable risk of serious injury Defences ➢ Intoxication: In some circumstances, the fact that the defendant was intoxicated during the commission of an offence might play a role in determining guilty. ➢ Self-induced intoxication cannot be used as a ‘substantial impairment’ defence (if you were spiked then yes/maybe) ➢ 428C(1) Evidence that a person was intoxicated (whether by reason of self-induced intoxication or otherwise) at the time of the relevant conduct m ay be taken into account in determining whether the person had the intention to cause the specific result necessary for an offence of specific intent. ➢ ‘428F Intoxication in relation to the reasonable person test: if the relevant offence is manslaughter, intoxication is taken into consideration in applying the reasonable person test:

❖ Mental illness (depression) → Porter, M’Naghten ➢ M’Naghten Case elements ■ Disease of the mind, Defect of reasoning, Did not know the nature and quality of the act, Did not know what she/he was doing wrong ➢ Elements must be proven by the accused on the balance of probabilities

R V Oscar # 1 Larceny ●

Oscar behaviour may also constitute to a criminal offence of larceny under s . 117 of the Crimes Act

●

AR according to I llich (1987) HC ○ Property capable of being stolen ■ Croton 1967: tangible property of having some value ■ Oscar had possession of the cleaning products which are a tangible and have value

●

○

Property in the possession of another ■ Constructive possession → According to W illiams v Phillips (1957) possession that is held by the employee/servant within the terms of their employment is considered to be constructively in the possession of the employer or master. Therefore, employees can steal from their employers.

○

Taken and Carried Away (asportation) ■ Applying Brennan J’s analysis of actus reus in He Kaw Teh, for the act to constitute the actus reus of larceny, it must occur in the circumstances where the property taken is larcenable, the property belongs to another and taking it without the consent of the possessor (Brown Et al 2015) ■ Wallis V Lane 1964 → ‘It would appear that any movement of goods with an intent to steal them is sufficient to constitute an asportation’ ■ Potisk (1973) → mere intention is sufficient

○

Taken without consent of the owner ■ Middleton (1873) → Must be taking invito domino (without the will of the owner)

MR ○

Intent to permanently deprive s.118 ■ Negates the defence of not intending to permanently deprive ■ Intention to eventually restore the property does mean acquittal ■ Foster 1967: Intention of taker to exercise ownership of the goods, to deal with them as his own, an intention to later restore the property will not prevent the original taking from being larcenous

●

156 Larceny by clerks or servants

Whosoever, being a clerk, or servant, steals any property belonging to, or in the possession, or power of, his or her master, or employer, or any property into or for which it has been converted, or exchanged, shall be liable to imprisonment for ten years.

Fraud . 192E of the Crimes Act 1900 (NSW) - ‘A person who, by any deception, dishonestly ❖ s obtains property belonging to another or obtains any financial advantage or causes any financial disadvantage is guilty of fraud’ ❖ AR 1. Deception ➔ 192B1(a): Deception is any words or other conduct that creates deception ‘as to the intentions of the person using deception’ ➔ Barnard (1837) → Conduct without words can create deception ➔ DPP v Ray [1974] → Judge held that the defendant had made a false representation by conduct 2. Obtaining property belonging to another person ➔ s.192C of the Crimes Act A person obtains property if he/she obtains ownership, possession or control of the property for himself or herself or for another person 3. Obtaining a Financial Advantage s. 192E - crimes act obtaining any financial advantage through deception is an element of fraud. ➔ Under s. 192D(1) obtaining financial advantage includes obtaining ‘ a financial advantage for oneself and to ‘keep a financial advantage that one has whether the financial advantage is permanent or temporary’. 4. Causing a Financial Disadvantage ➔ s. 192D(2) - cause a financial disadvantage to another person… whether the financial advantage is permanent or temporary ➔ On appeal Grey J in the case of Matthews v Fountain [1982] suggested that there were three bases on which financial advantage could exist. It could arise by: (1) the gaining of any extension of time in which to pay; (2) the avoidance of being harried by the creditor; or (3) the avoidance of the financial detriment involved in actually paying the debt

5. Causation ➔ Link b/w a person’s deception and obtaining property from another and/or obtaining financial advantage and/or causing financial disadvantage as outlined in the definition of fraud in s.192E of the crimes act Ho v Szeto (1989) there must be a causal connection between the deception used and the obtaining of property (or financial advantage or causing financial disadvantage)

❖ MR 1. Deception ➔ Under s. 1 92B 2 ‘A person does not commit an offence under this Part by a deception unless the deception was intentional or reckless’. ➔ As there is no statutory definition for recklessness, it is assumed that the applicable test is an awareness of the possibility that the behaviour is deceptive (S tokes v Difford 1990). 2. Obtaining Property Belonging to Another Person S. 192C (2) - ‘A person does not commit an offence under this Part by obtaining or intending to obtain property belonging to another unless the person intends to permanently deprive the other of the property’ 3. Obtaining a financial advantage and causing a financial disadvantage The law is silent on the mens rea for this element therefore case law is used. The case of He Kaw Teh 1985 suggests there needs to be an intentional or reckless foresight of the possibility of financial advantage which is subjective. ➔ Murphy (1987) further suggests only need to intend temporary financial advantage, not permanent. 4. Dishonest ➔ 4B: ‘dishonest means dishonest according to the standards of ordinary people and known by the defendant to be dishonest according to the standards of ordinary people.’

R V Oscar # 2 ➔ Common Assualt S. 61 Whosoever assaults any p erson, although not occasioning actual bodily harm, shall be liable to imprisonment for two years (caused ABH therefore not applicable) ➔ S.4 GBH any permanent or serious disfiguring of the person

❖ s. 59 (1) of the Crimes Act 1900 (NSW) - ‘Whosoever assaults any person, and thereby occasions actual bodily harm, shall be liable to imprisonment for five years’ ❖ AR ➢ There are two actus reus for assault occasioning actual bodily harm which include common assault and the occasioning of actual bodily harm Legislation is silent on the definition of common assault so it is defined by case law. Case law defines assault as ‘ an act by which a person intentionally or perhaps recklessly causes another person to apprehend the immediate infliction of unlawful force upon him’ as stated in Darby v DPP (NSW) (2004). Donovan [1934]. The case law suggests that the expression, ABH should be interpreted as the ordinary meaning of the words → “ bodily harm has its ordinary meaning and includes any hurt or injury calculated to interfere with the health of or comfort of the prosecutor. Such hurt or injury need not be permanent but must, no doubt, be more than mere transient or trifling". ❖ MR ➢ The mens rea of assault is often constituted by the intention to inflict an unlawful contact, or to create immediate and continuing fear of imminent unlawful contact in the mind of the other person, (Zanker v Vartzokis ). ➢ The question of whether recklessness can constitute mens rea instead of intention, and whether a subjective or objective test should be used, was considered in MacPherson v Brown. T he judge concluded that recklessness means “acting with foresight of the probable dangerous consequences of the act without even the desire for them ” .

❖ Defences

➢ ‘s418 Self-defence—when available: (1) A person is not criminally responsible for an offence if the person carries out the conduct constituting the offence in self-defence. ■ To satisfy the evidentiary burden, the accused must show sufficient nexus between offence and threat - there needs to be a relationship of (perceived) attack and a reasonable defence to it (proximity is relevant): B urgess; Saunders [2005]. ➢ ‘s419 Self-defence—onus of proof: In any criminal proceedings in which the application of this Division is raised, the prosecution has the onus of proving, beyond reasonable doubt, that the person did not carry out the conduct in self-defence.’ (underlining added) ■ The prosecution must disprove, beyond all reasonable doubt, the possibility of self-defence

➢ s418 (2) A person carries out conduct in self-defence if and only if the person believes the conduct is necessary: (a) to d efend himself or herself or another person ■ Necessarily of response ■ The questions to be asked by the jury under s 418(2) are succinctly set out in R v Katarzynski [2002] → It is for the jury to decide which circumstances they take into account ■ The trial judge has the power to remove self-defence from the jury’s consideration - R v PRFN ■ In order for self-defence to be raised or left to the jury there must be evidence capable of supporting a reasonable doubt in the mind of the tribunal of fact as to whether the prosecution has excluded self-defence: Colosimo v DPP [2006]

Essays 1. Domestic Violence case studies & stuff The court process in the Local Court in NSW for dealing with applications for apprehended domestic violence orders does not adequately protect victims of domestic violence from further violence. Discuss with reference o nly to the set readings in weeks 1 and 2, the week 2 seminar on domestic violence, and your observations at court. If you did not observe any applications for apprehended domestic violence orders at court, you may refer to relevant matters in the DVD So Help Me God. ❖ Domestic violence are acts of violence that occur between people who have, or have had, an intimate relationship in domestic settings. These acts include physical, sexual, emotional and psychological abuse. Court Process in the Local Court → McBarnet ● Argues that the two tiers of justice refers to the different levels of justice obtained in the upper and lower courts. ● McBarnet argues that one tier, the higher courts, “is for public consumption, the arena where the ideology of justice is put on display. The other, the lower courts, deliberately structured in defiance of the ideology of justice, is concerned less with subtle ideological messages than with direct control” ● Magistrate’s speedy deliberation over the various matters heard over the span of just 9:30 - 11 (observations at court) ● Mark and Roach Anleu argue that magistrates must deal with individual matters very quickly to get through the criminal list scheduled for the same time block. Makes it impossible to know which matters will be heard at all and which will require significant time and attention and how long the list will take. Apprehended Domestic Violence Orders Brown et al ● In 2007, the domestic violence provisions were transferred out of the Crimes Act and were given their own Act: the Crimes (Domestic and Personal Violence) Act 2007. This provided a dual system of apprehended domestic violence orders (ADVOs) and apprehended personal violence orders (APVOs) ●

The act, as outlined in s.9, aims to ensure the safety and protection of all persons who experience or witness domestic violence by empowering courts to make ADVOs to protect people from domestic violence, intimitation and stalking, and ensuring that access to courts is as safe, speedy, inexpensive and simple ad is consistent with justice

●

Under S. 16 A court may, on application, make an apprehended domestic violence order if it is satisfied on the balance of probabilities that a person who has or has had a domestic relationship with another person has reasonable grounds to fear the commission of a person violence offence against them

●

Mandatory orders - The orders state that you must not ○ assault or threaten the protected person or any other person having a domestic relationship with the protected person ○ stalk, harass or intimidate the protected person or any other person having a domestic relationship with the protected person intentionally ○ recklessly destroy or damage any property that belongs to or is in the possession of the protected person or any other person having a domestic relationship with the protected person

●

Court observations. For every ADVO matter the magistrate stated. If you break the bond the police are called - bail refused - gaol

●

The Crimes (Domestic and Personal Violence) Amendment Act 2013, which amended the Crimes (Domestic and Personal Violence) Act 2007, wrought a major change on the domestic violence regime in NSW. A Senior Police officer may now make provisional apprehended domestic violence orders (ADVOs) if they have “reasonable grounds” to deem it necessary. The ADVO then must be listed before a Local Court on the next domestic violence "list' day and no more than 28 days from the date it was made.

Not adequately protect victims of domestic violence from further violence ● Generally just a piece of paper - defendant chooses whether to follow it or not ● In practice DV continues to be mainly dealt with as a civil matter through DV protection order legislation rather than as a criminal matter → recognising DV as a crime will both improve victim safety and secure community denunciation (Brown et el) ● According to the ABS (2006) Personal Safety Survey , approximately one in three Australian women have experienced physical violence during their lifetime, nearly one in five women have experienced some form of sexual violence and nearly one in five have experienced violence by a current or previous partner ● One woman is Killed by her current or former partner almost every week in Australia (2013 National Community Attitudes Towards Violence Against Women, VicHeath) ● In 2006–07, one in five homicides involved intimate partners and more than half of all female victims were killed by their intimate partner (Dearden & Jones 2008). ●

J Byles at el, “The Effectiveness of Legal Protection in the Prevention of DV in the Lives of Young Australian Women”, 2000 ○ A sense of injustice was expressed by women who were successful in obtaining an AVO because breaches of orders were not responded to, or because the levels of sanctions for the abusive behaviour were seen as manifestly inadequate by the victims ○ Violence occurred after legal protection for half the women

●

ABS Personal Safety Survey (2012) ○ Of the 536, 900 women who had contacted police about the most recent violence, 50% also had a restraining order (i.e. an AVO) issued against their partner. ○ Of those women who had a restraining order issued against their partner, 58% experienced further violence

2. Aboriginals case studies & stuff The gross overrepresentation of Indigenous Australians in the statistics for offensive language and offensive behaviour is a consequence of the practices and legacies of colonisation. Discuss with reference only to the set readings for Criminal Law this semester. Practices and Legacies of Colonisation ❖ Colonial legal theory suggests that NSW was a ‘settled colony’ at the time of colonisation in 1901. ❖ The doctrine of terra nullius was established quickly → ‘land belonging to no one’. ❖ The Doctrine of Terra Nullius was not overturned until the High Court decision of Mabo v Queensland (No 2) in 1992. Although this was a victory for Indigenous Australians, it was also a huge factor in highlighting just how long injustice had been present in Australian society. H Reynolds, Frontier (Practices & Ideology) Criminality has almost become akin to Aboriginality when considering ideological means to justify rape and murder, such as ‘doing the needful’ and ‘a pleasurable excitement’ ➢ “Settlers developed a collection of euphemisms to facilitate discussion of frontier brutality”. Murder was referenced as “dispersals” which “meant nothing but firing into them for that purpose” (Queensland Attorney General, 1861) ➢ Documents recounting the murder of 300 Aboriginals in response to to the murder of a prominent white as ‘punitive expeditions mounted by both squatters and Native Police’ ➢ Killed for the purpose of ‘disbursement’ and was commonly noted in newspapers –never referring to them as men/women/children as a means of removing them from humanity ➢ ‘To shoot them dead would be no more moral evil than destroying of rats by poison’ ➢ Rape & abduction of women - “...

Similar Free PDFs

Notes - Summary Criminal Law

- 12 Pages

Crim notes - Summary Criminal Law

- 60 Pages

Criminal law course summary

- 109 Pages

Summary, Criminal Law

- 11 Pages

Criminal Law - Rape Summary

- 5 Pages

Criminal law notes

- 41 Pages

Popular Institutions

- Tinajero National High School - Annex

- Politeknik Caltex Riau

- Yokohama City University

- SGT University

- University of Al-Qadisiyah

- Divine Word College of Vigan

- Techniek College Rotterdam

- Universidade de Santiago

- Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Johor Kampus Pasir Gudang

- Poltekkes Kemenkes Yogyakarta

- Baguio City National High School

- Colegio san marcos

- preparatoria uno

- Centro de Bachillerato Tecnológico Industrial y de Servicios No. 107

- Dalian Maritime University

- Quang Trung Secondary School

- Colegio Tecnológico en Informática

- Corporación Regional de Educación Superior

- Grupo CEDVA

- Dar Al Uloom University

- Centro de Estudios Preuniversitarios de la Universidad Nacional de Ingeniería

- 上智大学

- Aakash International School, Nuna Majara

- San Felipe Neri Catholic School

- Kang Chiao International School - New Taipei City

- Misamis Occidental National High School

- Institución Educativa Escuela Normal Juan Ladrilleros

- Kolehiyo ng Pantukan

- Batanes State College

- Instituto Continental

- Sekolah Menengah Kejuruan Kesehatan Kaltara (Tarakan)

- Colegio de La Inmaculada Concepcion - Cebu