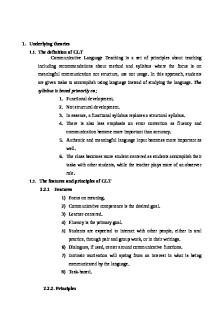

Summary of Communicative Language teaching PDF

| Title | Summary of Communicative Language teaching |

|---|---|

| Course | Education (TESOL) |

| Institution | University of Nottingham |

| Pages | 27 |

| File Size | 342.5 KB |

| File Type | |

| Total Downloads | 80 |

| Total Views | 145 |

Summary

Summary of Communicative Language teaching...

Description

Communication Language Teaching Use of language instead of language knowledge The point has already been made that the ‘teaching content’ approach to communicative language teaching base itself on a linguistic insight regarding what is entailed in knowing a language and that now, following Hynes (1979), a revised view of language competence is generally accepted. Use of the word ‘knowing’ in this context conjures up the spectre for a wellaired issue in applied linguistics -that ‘knowledge of a language’ is not the same thing as ‘ability to use the language’. It was often said of the grammar-translation method that it provided knowledge without skills. (Johnson, 1979) Understanding of CLT can be traced to concurrent developments in Europe and North American. In Europe,…The syllabus was derived from neo-firthian systemic or functional linguistics, in which language is viewed as “meaning potential”, and the “context of situation” (Firth 1937; Halliday 1979) is viewed as central to understanding language systems and how they work…. Language functions based on an assessment of the communicative needs of learners specified the end results, or goal, of an instructional program. The term communicative attached itself to programs that used a notional-functional syllabus based on needs assessment, and the language for specific purposes (LSP) movement was launched. Savignon, S. J. (2006)

Concurrent development in Europe focused on the process of communicative classroom language learning. …. Language teaching methodologists took the lead in developing classroom materials that encouraged learner choice. (Candline, 1978).. Exercise were designed to exploit the variety of social meanings contained within particular grammatical structures. … Supplementary teacher resources promoting classroom CLT became increasingly popular in the 1970s. Savignon, S. J. (2006)

Hymes had written it as a deliberate comment on Chomsky’s use of the term ‘competence’ the previous year in Aspects of the Theory of Syntax (1965), a book that had lifted its author’s reputation to the peak of his profession. In Aspects Chomsky used ‘competence’ to refer to ‘the speaker-hearer’s knowledge of his language’, in contrast to ‘performance’ which meant the actual use of language. But he went much further than any of his predecessors when he dedicated linguistics itself to the study of ‘competence’, and in doing so he underlined his conviction that ‘language’ was essentially a mental rather than a social process. By adding ‘communicative’ Hymes intended to remind people that Chomsky’s definition was deficient in respect of dimension of knowledge that had to do with the communication of meaning or, to use his famous aphorism: ‘there are rules of use without which the rules of grammar would be useless’. When ‘communicative competence’ reached the UK some years later (c. 1972), it caught the spirit of the times and its alliterative properties no doubt helped it to become the

1

motto of the new approach to language teaching. Also by this time there were positive research results to report from America which further enhanced its influence (refer to Savignon, 1972) (Howatt and Widdowson, 2004)

Focus on meaning, focus on communication Berns (1990), 104) provides a useful summary of eight principles of CLT: Language teaching is based on a view of language as communication. That is, language is seen as a social tool that speakers use to make meaning; speakers communicate about something to someone for some purpose, either orally or in writing. (Savignon, 2006)

So what is CLT about? The name is a give-away: the central theme of the approach is to underscore the importance of meaningful communication and usable commutative skills in L2 instruction. In other words of one of the founders of the approach, Sandra Savignon (1990: 210), the primary focus in CLT was ‘the elaboration and implementation of programmes and methodologies that promote the development of L2 functional competence through learner participation in communicative events’. In this sense, therefore, CLT pursued every similar goals to those of the audiolingual methods, which is interesting given that CLT is often seen as a reaction to audiolingualism. The reason for this seeming contradiction lies in the very different ways by which the two approaches intended to build up an implicit knowledge base in the learners. In contrast to the key audiolingual techniques of automatization through drilling and memorization, CLT methodology was centred around the learner’s participatory experience in meaningful L2 interaction in (often simulated) communicative situation, which underscored the significance of less structured and more creative language tasks. For this reason, the leaning of scripted dialogues was replaced by games, problem-solving tasks, and unscripted situational role-plays, and pattern drilling was either completely abandoned or replaced by ‘communicative drills’ Regarding the latter, Lightbown (2008) points out that the term may sound like an oxymoron to many SLA researchers and teachers, yet such controlled communicative practice tasks can be designed in the sense that although they make repeated use of a small sample of utterances, they do so in situations where the learners have to choose the utterance that fits the specific meaning they want to convey. (Dörnyei, 2009). CLT thus can be seen to derive from a multidisciplinary perspective that includes linguistics, anthropology, philosophy, sociology, psychology, and educational research. (Savignon, 2006)

One of the key principles from which I have taken my bearings in writing this book is that language exists to fulfil a range of communicative functions, and that these functions will be reflected in the shape of the language itself. This principle can be used to guide teaching decisions, and to inform a range of curriculum tasks, from the selection and grading of content,

2

through to the selection of learning tasks and material. In this chapter we see how it can provide useful insight for both the theory and practice of writing. (Nunan, 1995)

Process vs Product / ends and means One of the clearest presentations of a syllabus proposal based on process rather than products has come from Breen. He suggests that an alternative to the listing of linguistic content (the end point, as it were, in the learner’s journey) would be to: …prioritize the route itself; a focusing upon the means toward the learning of a new language. Here the design would give priority to the changing process of learning and the potential of the classroom – to the psychological and social resources applied to a new language by learners in the classroom context … a greater concern with capacity for communication rather than repertoire of communication, with the activity of learning a language viewed as important as the language itself, and with a focus upon means rather than predetermined objectives, all indicate priority of process over content. (Breen 1984: 52-3) What Breen is suggesting is that, with communication at the centre of the curriculum, the goal of that curriculum (individuals who are capable of using the target language to communicate with others) and the means (classroom activities which develop this capacity) begin to merge; the syllabus must take account of both the ends and the means. Syllabus: will include some/all of the following: structures, functions, notions, themes, tasks. Ordering will be guided by learner needs. (Nunan, 1989) Both schools emphasize the process rather than the product…. Communicative language teaching (CLT) refers to both process and goals in classroom learning. Savignon, S. J. (2002) The essence of CLT is the engagement of learners in communication to allow them to develop their communicative competence. Use of the term ‘communicative’ in reference to language teaching refers to both the process and goals of learning. Savignon, S. J. (2006)

Its (CLT) focus has been the elaboration and implementation of programs and methodologies that promote the development of functional language ability through learner participation in communicative events. (Savignon, 2006)

Richards and Rodgers (1986, p.66) state that “the aims of CLT are to 3

make communicative competence the goal of language teaching and to develop procedures for the teaching of the four language skills that acknowledge the interdependence of language and communication”. (Xie, 2013) This is certainly Littlewood’s (1981) view. In his introduction to communicative language teaching, he suggests that the following skills need to be take into consideration: -

-

-

-

The learner must attain as high a degree as possible of linguistic competence. That is, he must develop skill in manipulating the linguistic system, to the point where he can use it spontaneously and flexibly in order to express his intended message. The learner must distinguish between the forms he has mastered as part of his linguistic competence, and the communicative functions which they perform. In other words, items mastered as part of a linguistic system must also be understood as part of a communicative system. The learner must develop skills and strategies for using language to communicate meanings as effectively as possible in concrete situations. He must learn to use feedback to judge his success, and if necessary, remedy failure by using different language. The learner must become aware of social meaning of language forms. For many learners, this may not entail the ability to vary their own speech to suit different social circumstances, but rather the ability to use generally acceptable forms and avoid potentially offensive ones. (Littlewood 1981: 6)

I take the view that any comprehensive curriculum needs to take account of both means and ends and must address both content and process. What matters is that both process and outcomes are taken care of and that there is a compatible and creative relationships between the two. (Nunan, 1989)

Related learning theory; Not the forms of activity, should be profound change in the methodology A second difference between audiolingual and communicative attempts at developing productive L2 competence concerned the fact that while audiolingualism was associated with a specific learning theory – behaviourism – the communicative reform was centred around the radical renewal of the linguistic course content without any systematic psychological conception of learning to accompany it. Thus, while communicative syllabuses were informed by Austin (1962) and Searle’s (1969) speech act theory, Hymes’s (1972) model of communicative competence and its application to L2 proficiency by Canale and Swain (1980; Canale 1983), as well as Halliday’s (1985) systemic functional grammar, the only learningspecific principle that was available for CLT material developers and practitioners was the broad guideline to develop the learners’ communicative competence through their active participation in seeking situational meaning. The imbalance between innovation in linguistic content and learning method was already expressed by Brumfit (1979:187) in the early days of CLT development: 4

There has been a widespread assumption that communicative teaching should not simply be a matter of the specification of the elements in a course, but that it should involve a profound change in the methodology. Yet it is noteworthy that most discussion has been based on long-standing procedures, such as use of group and pair work, simulation and role-pay exercise, and other techniques which have been used, though possibly more in the second than the foreign language situation, for many years. (Dörnyei, 2009). Fluency over accuracy It might be worth considering, however, what would be the implications if we used fluency as the basis for a language curriculum, rather than accuracy. The reason for being uncertain about the wholly desirable effects of the accuracy basis can be stated fairly briefly. First of all, ‘accuracy’ is a relative term, based on a social judgement of the language used by a speech community. When, for the teacher, an idealized accuracy is set up, it must be based on a model (which may or may not have a strong empirical source) devised by a descriptive linguist. Such a model is most frequently based on literary sources, though it need not be, and it always involves a strong degree of idealization. Pedagogically, it can be justified only as a short cut, as a way of enshrining the central truth of the target language, so that subsequent modification can take place as experience is gained of a wider and wider variety of situations. To insist on a model of accuracy, whether conceived in grammatical or functional terms, entails taking a number of risks: that inflexibility will be trained through too close a reference to a descriptive model, that adaptability and the ability to improvise will be neglected, that written forms will tend to dominate spoken forms, and so on. (Brumfit, 1979)

No fixed model, but it is combination of implicit skills and explicit knowledge Berns (1990), 104) provides a useful summary of eight principles of CLT: 1. No single methodology or fixed sent of techniques is prescribed. (actually 6) (Savignon, 2006)

Partly because of the vagueness of the ‘seeking situational meaning’ tenet, since the genesis of CLT in the early 1970s in the UK and the United States its proponents have developed a very wide range of variants that were only loosely related to each other. Thus, Richards and Rogers (2001; 155) rightly point out about CLT that ‘There is no single text or authority on it, more any single model that is universally accepted as authoritative.’ (Dörnyei, 2009).

In spite of the emphasis of the leading theorists of the CLT movement that ‘ the new importance attached to function should not be bought at the expense of form’(Cook, 2000: 5

189), the emerging view of typical communicative classroom was that it approximates to a naturalistic SLA environment as closely as possible, thereby providing plenty of authentic input to feed the students’ implicit learning processes without necessarily involving conscious attention to rules. Unfortunately, as we saw earlier in this chapter, relying on a purely implicit learning approach has turned out to be less than successful in SLA in general and therefore the past decade has seen a transformation of our idealized CLT image. ’ (Dörnyei, 2009). In her summary of this shift, Spada (2007; 271) explained that ‘most second language educators agree that CLT is undergoing a transformation – one that includes increased recognition of and attention to language form within exclusively or primarily meaning-oriented CLT approaches to second language instruction’. It was in this vein that in 1997 Marianne CeleMurcia, Sarah Thurrel and I suggested (Celce-Murcia, Dörnyei and Thurrell, 1997, see also 1998) that CLT has arrived at a new phase that we termed ‘principled communicative language teaching’: In sum, we believe that CLT has arrive at a turning point: Explicit, direct element are gaining significance in teaching communicative abilities and skills. The emerging new approach can be described as a principled communicative approach; by bridging the gap between current research on aspects of communicative competence and actual communicative classroom practice, this approach has the potential to synthesize direct, knowledge-oriented and indirect, skill-oriented teaching approaches. Therefore, rather than being a complete departure from the original, indirect practice of CLT, it extends and further develops CLT methodology. (Cele-Murcia et al, 1997: 147-148) (Dörnyei, 2009).

The prevailing view seemed to be that the bad old days of behaviourist drilling had long gone and this left the profession free to choose from a battery of teaching techniques as and when they seemed relevant and/or useful. Three approaches in particular found favour among teachers and course designers. One was role-playing or simulation where learners either enacted a communicative event from memorized text, or improvised one from give guidelines. The second was ‘problem solving’ which had considerable appeal in ESP because it carried research connotations. It was also popular with teachers of a progressive turn of mind who saw it as the heir of ‘discovery method’ going right back to Rousseau. But probably the most popular model was skill training which had the advantages of representing a reasonably holistic view of learning while at the same time permitting the exercise of specific components. All these approaches were effective enough, but they did not add up to a coherent theory of language learning, and CLT did not really want one. (Howatt and Widdowson, 2004)

The form that communicative approach presents can be varied rather than being restricted to group activities in which focused on oral communication practice. It is possible to incorporate cognitive teaching of grammar which "should be taught more liberally, with greater respect of the individual" (Holliday 1994, p.167). (Xie, 2013)

6

Strong version and weak version More generally, the legacy of the CLT classroom that distinguishes it most clearly from its predecessors is probably the adoption of the concept of ‘activities’….Every now and then there were rather ill-defined tasks like essay-writing or ‘conversation’, which were supposed to revise the language that had already been taught and give students an opportunity of using it to express themselves. However, the idea of focused activities expressly designed to get learners to draw on their communicative resources in order to product appropriate language…. With CLT, however, work of this kind was seen as a necessary conclusion to a new tripartite lesson design which teachers sometimes refer to as ‘PPP’ (presentation, practice and production). (Howatt and Widdowson, 2004)

(Task-based)… A communicative methodology, then, would start from communication, with exercise which constituted communication challenges for students. As they attempted the exercises, student would have to stretch their linguistic capabilities to perform the given tasks, and would be given subsequent teaching, which could be of a traditional form, where they clearly perceived themselves to need to improve to establish communication adequately in relation to the task. Such a procedure is not simply an answer to a motivation problem; even more it is a matter of learning principles, for the complexity of the linguistic and communicative systems being operated require that new learning must be closely assimilated with what is already known, and if language is being learnt for use, the new learning must be directly associated with use…. The old question of what learners use the language for, what subject matter is appropriate, takes on a new urgency. (Brumfit, 1979)

Activity types: Engage learners in communication, involve process such as information sharing, negotiation of meaning and interaction (Nunan, 1989)

Theoretical base Theory of language: Language is a system for the expression of meaning; primary functioninteraction and communication. Theory of learning: Activities involving real communication; carrying our meaningful tasks; and using language which is meaningful to the learner promote learning. (Nunan, 1989)

7

It has been accepted that language is more than simply a system of rules. Language is now generally seen as a dynamic resource for the creation of meaning. In terms of learning, it is generally accepted that we need to distinguish between ‘learning that’ and ‘knowing how’. In other words, we need to distinguish between knowing various grammatical rules and being able to use the rules effectively and appropriated when communicating. This view has underpinned CLT. (Nunan, 1989)

Mis concepts: CLT does not including grammar teaching The large amount of attention that was given to focus on meaning and language abilities in communicative purposes...

Similar Free PDFs

Communicative Language Teaching

- 3 Pages

Task-based language teaching

- 238 Pages

English Language Teaching

- 9 Pages

English Language Teaching

- 7 Pages

Communicative

- 20 Pages

Methodology in Language Teaching

- 433 Pages

English Language Teaching

- 16 Pages

LANGUAGE TEACHING MEDIA

- 1 Pages

Popular Institutions

- Tinajero National High School - Annex

- Politeknik Caltex Riau

- Yokohama City University

- SGT University

- University of Al-Qadisiyah

- Divine Word College of Vigan

- Techniek College Rotterdam

- Universidade de Santiago

- Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Johor Kampus Pasir Gudang

- Poltekkes Kemenkes Yogyakarta

- Baguio City National High School

- Colegio san marcos

- preparatoria uno

- Centro de Bachillerato Tecnológico Industrial y de Servicios No. 107

- Dalian Maritime University

- Quang Trung Secondary School

- Colegio Tecnológico en Informática

- Corporación Regional de Educación Superior

- Grupo CEDVA

- Dar Al Uloom University

- Centro de Estudios Preuniversitarios de la Universidad Nacional de Ingeniería

- 上智大学

- Aakash International School, Nuna Majara

- San Felipe Neri Catholic School

- Kang Chiao International School - New Taipei City

- Misamis Occidental National High School

- Institución Educativa Escuela Normal Juan Ladrilleros

- Kolehiyo ng Pantukan

- Batanes State College

- Instituto Continental

- Sekolah Menengah Kejuruan Kesehatan Kaltara (Tarakan)

- Colegio de La Inmaculada Concepcion - Cebu