all chapter Chemistry a molecular approach 5th edition Nivaldo Tro solutions manual pdf PDF

| Title | all chapter Chemistry a molecular approach 5th edition Nivaldo Tro solutions manual pdf |

|---|---|

| Author | farsh sardar |

| Course | Molecular Pharmacology |

| Institution | University of Auckland |

| Pages | 19 |

| File Size | 1.2 MB |

| File Type | |

| Total Downloads | 13 |

| Total Views | 145 |

Summary

Authors: Nivaldo J. Tro

Published: Pearson 2019

Edition: 5th

Pages: 1009

Type: pdf

Size: 226MB

Download After Payment...

Description

FOLFNKHUHWRGRZQORDG

SOLUTIONS MANUAL Kathleen Thrush Shaginaw Community College of Philadelphia Particular Solutions, Inc.

CHEMISTRY A Mol e cu l Ar Ap p r oAch F if t h e dit io n

NivAldo J. Tro

@solutionmanual1

FOLFNKHUHWRGRZQORDG Director, Physical Science Portfolio Management: Jeanne Zalesky Executive Courseware Portfolio Manager, General Chemistry: Terry Haugen Courseware Portfolio Manager Assistant: Harry Misthos Executive Field Marketing Manager: Christopher Barker Senior Product Manager: Elizabeth Bell Managing Producer, Science: Kristen Flathman Senior Content Producer, Science: Beth Sweeten Production Management and Composition: Pearson CSC Senior Procurement Specialist: Stacey Weinberger Cover Illustration: Quade Paul Copyright © 2020, 2017, 2014 by Pearson Education, Inc. 221 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030. All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission should be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction, storage in a retrieval system, or transmission in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise. For information regarding permissions, request forms and the appropriate contacts within the Pearson Education Global Rights & Permissions department, please visit www.pearsoned.com/permissions/. Unless otherwise indicated herein, any third-party trademarks that may appear in this work are the property of their respective owners and any references to third-party trademarks, logos or other trade dress are for demonstrative or descriptive purposes only. Such references are not intended to imply any sponsorship, endorsement, authorization, or promotion of Pearson’s products by the owners of such marks, or any relationship between the owner and Pearson Education, Inc. or its affiliates, authors, licensees or distributors. PEARSON, ALWAYS LEARNING and MasteringChemistry are exclusive trademarks in the U.S. and/or other countries owned by Pearson Education, Inc. or its affiliates.

@solutionmanual1

ISBN-10: 0-13-498981-3 ISBN-13: 978-0-13-498981-5

FOLFNKHUHWRGRZQORDG

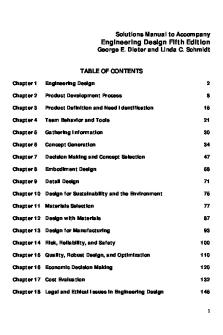

Contents

Student Guide to Using This Solutions Manual ...........................................................iv Chapter 1

Matter, Measurement, and Problem Solving .................................................................1

Chapter 2

Atoms and Elements ....................................................................................................38

Chapter 3

Molecules and Compounds..........................................................................................69

Chapter 4

Chemical Reactions and Chemical Quantities ..........................................................115

Chapter 5

Introduction to Solutions and Aqueous Reactions ....................................................147

Chapter 6

Gases ..........................................................................................................................170

Chapter 7

Thermochemistry .......................................................................................................216

Chapter 8

The Quantum-Mechanical Model of the Atom .........................................................257

Chapter 9

Periodic Properties of the Elements ..........................................................................286

Chapter 10

Chemical Bonding I: The Lewis Theory ...................................................................311

Chapter 11

Chemical Bonding II: Molecular Shapes, Valence Bond Theory, and Molecular Orbital Theory ...................................................................................384

Chapter 12

Liquids, Solids, and Intermolecular Forces ...............................................................436

Chapter 13

Crystalline Solids and Modern Materials ..................................................................459

Chapter 14

Solutions ....................................................................................................................475

Chapter 15

Chemical Kinetics ......................................................................................................523

Chapter 16

Chemical Equilibrium ................................................................................................566

Chapter 17

Acids and Bases .........................................................................................................606

Chapter 18

Aqueous Ionic Equilibrium........................................................................................663

Chapter 19

Free Energy and Thermodynamics ............................................................................753

Chapter 20

Electrochemistry ........................................................................................................810

Chapter 21

Radioactivity and Nuclear Chemistry........................................................................862

Chapter 22

Organic Chemistry .....................................................................................................890

Chapter 23

Biochemistry ..............................................................................................................933

Chapter 24

Chemistry of the Nonmetals ......................................................................................950

Chapter 25

Metals and Metallurgy ...............................................................................................972

Chapter 26

Transition Metals and Coordination Compounds ......................................................985

iii @solutionmanual1 Copyright © 2020 Pearson Education, Inc.

FOLFNKHUHWRGRZQORDG

Student Guide to Using This Solutions Manual

The vision of this solutions manual is to provide guidance that is useful for both the struggling student and the advanced student. An important feature of this solutions manual is that answers for the review questions are given. This will help in the review of the major concepts in the chapter. The format of the solutions very closely follows the format in the textbook. Each mathematical problem includes Given, Find, Conceptual Plan, Solution, and Check sections.

Conceptual Plan: The conceptual plan shows a step-by-step method to solve the problem. In many cases, the given quantities need to be converted to a different unit. Under each of the arrows is the equation, constant, or conversion factor needed to complete this portion of the problem. In the “Problems by Topic” section of the end-of-chapter exercises, the oddnumbered and even-numbered problems are paired. This allows you to use a conceptual plan from an odd-numbered problem in this manual as a starting point to solve the following even-numbered problem. Students should keep in mind that the examples shown are one way to solve the problems. Other mathematically equivalent solutions may be possible.

Given and Find: Many students struggle with taking the written problem, parsing the information into categories, and determining the goal of the problem. It is also important to know which pieces of information in the problem are not necessary to solve the problem and if additional information needs to be gathered from sources such as tables in the textbook.

6.45

Given: m 1CO22 = 28.8 g, P = 742 mmHg, and T = 22 °C Find: V Conceptual Plan: °C u K and mmHg u atm and g u mol then n, P, T u V K = °C + 273.15

1 atm 760 mmHg

1 mol 44.01 g

Solution: T1 = 22 °C + 273.15 = 295 K, P = 742 mmHg *

PV = nRT

1 atm = 0.976316 atm 760 mmHg

1 mol = 0.654397 mol PV = nRT Rearrange to solve for V. 44.01 g L # atm * 295 K 0.654397 mol * 0.08206 mol # K nRT = 16.2 L V = = P 0.976316 atm n = 28.8 g *

Check: The units (L) are correct. The magnitude of the answer (16 L) makes sense because one mole of an ideal gas under standard conditions (273 K and 1 atm) occupies 22.4 L. Although these are not standard conditions, they are close enough for a ballpark check of the answer. Because this gas sample contains 0.65 mol, a volume of 16 L is reasonable.

Solution: The Solution section walks you through solving the problem after the conceptual plan. Equations are rearranged to solve for the appropriate quantity. Intermediate results are shown with additional digits to minimize round-off error. The units are canceled in each appropriate step.

Check: The Check section confirms that the units in the answer are correct. This section also challenges the student to think about whether the magnitude of the answer makes sense. Thinking about what is a reasonable answer can help uncover errors such as calculation errors.

iv @solutionmanual1

Copyright © 2020 Pearson Education, Inc.

FOLFNKHUHWRGRZQORDG

1

Matter, Measurement, and Problem Solving

Review Questions 1.1

“The properties of the substances around us depend on the atoms, ions, or molecules that compose them” means that the specific types of atoms and molecules that compose something tell us a great deal about which properties to expect from a substance. A material composed of only sodium and chloride ions will have the properties of table salt. A material composed of molecules with one carbon atom and two oxygen atoms will have the properties of the gas carbon dioxide. If the atoms and molecules change, so do the properties that we expect the material to have.

1.2

The main goal of chemistry is to seek to understand the behavior of matter by studying the behavior of atoms and molecules.

1.3

The scientific approach to knowledge is based on observation and experimentation. Scientists observe and perform experiments on the physical world to learn about it. Observations often lead scientists to formulate a hypothesis, a tentative interpretation or explanation of their observations. Hypotheses are tested by experiments: highly controlled procedures designed to generate such observations. The results of an experiment may support a hypothesis or prove it wrong—in which case the hypothesis must be modified or discarded. A series of similar observations can lead to the development of a scientific law: a brief statement that summarizes past observations and predicts future ones. One or more wellestablished hypotheses may form the basis for a scientific theory. A scientific theory is a model for the way nature is and tries to explain not merely what nature does, but why. The Greek philosopher Plato (427–347 b.c.) took an opposite approach. He thought that the best way to learn about reality was not through the senses, but through reason. He believed that the physical world was an imperfect representation of a perfect and transcendent world (a world beyond space and time). For him, true knowledge came not through observing the real physical world, but through reasoning and thinking about the ideal one.

1.4

A hypothesis is a tentative interpretation or explanation of the observed phenomena. A law is a concise statement that summarizes observed behaviors and observations and predicts future observations. A theory attempts to explain why the observed behavior is happening.

1.5

Antoine Lavoisier studied combustion and carefully measured the mass of objects before and after burning them in closed containers. He noticed that there was no change in the total mass of material within the container during combustion. Lavoisier summarized his observations on combustion with the law of conservation of mass, which states, “In a chemical reaction, matter is neither created nor destroyed.”

1.6

John Dalton formulated the atomic theory of matter. Dalton explained the law of conservation of mass, as well as other laws and observations of the time, by proposing that matter was composed of small, indestructible particles called atoms. Because these particles were merely rearranged in chemical changes (and not created or destroyed), the total amount of mass would remain the same.

1.7

The statement “that is just a theory” is generally taken to mean that there is no scientific proof behind the statement. This statement is the opposite of the meaning in the context of the scientific theory, where theories are tested again and again.

1 @solutionmanual1 Copyright © 2020 Pearson Education, Inc.

2

Chapter 1 Matter, Measurement, and Problem Solving

FOLFNKHUHWRGRZQORDG

1.8

Matter can be classified according to its state—solid, liquid, or gas—and according to its composition.

1.9

In solid matter, atoms or molecules pack close to each other in fixed locations. Although the atoms and molecules in a solid vibrate, they do not move around or past each other. Consequently, a solid has a fixed volume and a rigid shape. In liquid matter, atoms or molecules pack about as closely as they do in solid matter, but they are free to move relative to each other, giving liquids a fixed volume but not a fixed shape. Liquids assume the shape of their container. In gaseous matter, atoms or molecules have a lot of space between them and are free to move relative to one another, making gases compressible. Gases always assume the shape and volume of their container.

1.10

Solid matter may be crystalline, in which case its atoms or molecules are arranged in patterns with long-range, repeating order; or it may be amorphous, in which case its atoms or molecules do not have any long-range order.

1.11

A pure substance is composed of only one type of atom or molecule. In contrast, a mixture is a substance composed of two or more different types of atoms or molecules that can be combined in variable proportions.

1.12

An element is a pure substance that cannot be decomposed into simpler substances. A compound is composed of two or more elements in fixed proportions.

1.13

A homogeneous mixture has the same composition throughout, while a heterogeneous mixture has different compositions in different regions.

1.14

If a mixture is composed of an insoluble solid and a liquid, the two can be separated by filtration, in which the mixture is poured through filter paper (usually held in a funnel).

1.15

Mixtures of miscible liquids (substances that easily mix in all proportions) can usually be separated by distillation, aprocess in which the mixture is heated to boil off the more volatile (easily vaporizable) liquid. The volatile liquid is then recondensed in a condenser and collected in a separate flask.

1.16

A physical property is one that a substance displays without changing its composition, whereas a chemical property is one that a substance displays only by changing its composition via a chemical change.

1.17

Changes that alter only state or appearance, but not composition, are called physical changes. The atoms or molecules that compose a substance do not change their identity during a physical change. For example, when water boils, it changes its state from a liquid to a gas, but the gas remains composed of water molecules; so this is a physical change. When sugar dissolves in water, the sugar molecules are separated from each other, but the molecules of sugar and water remain intact. In contrast, changes that alter the composition of matter are called chemical changes. During a chemical change, atoms rearrange, transforming the original substances into different substances. For example, the rusting of iron, the combustion of natural gas to form carbon dioxide and water, and the denaturing of proteins when an egg is cooked are examples of chemical changes.

1.18

In chemical and physical changes, matter often exchanges energy with its surroundings. In these exchanges, the total energy is always conserved; energy is neither created nor destroyed. Systems with high potential energy tend to change in the direction of lower potential energy, releasing energy into the surroundings.

1.19

Chemical energy is potential energy. It is the energy that is contained in the bonds that hold the molecules together. This energy arises primarily from electrostatic forces between the electrically charged particles (protons and electrons) that compose atoms and molecules. Some of these arrangements—such as the one within the molecules that compose gasoline—have a much higher potential energy than others. When gasoline undergoes combustion, the arrangement of these particles changes, creating molecules with much lower potential energy and transferring a great deal of energy (mostly in the form of heat) to the surroundings. A raised weight has a certain amount of potential energy (dependent on how high the weight is raised) that can be converted to kinetic energy when the weight is released.

1.20

The SI base units include the meter (m) for length, the kilogram (kg) for mass, the second (s) for time, and the kelvin (K) for temperature.

1.21

The three different temperature scales are kelvin (K), Celsius(°C), and Fahrenheit (°F). The size of the degree is the same in the kelvin and the Celsius scales; and the degree size is 1.8 times larger than the degree size for the Fahrenheit scale.

@solutionmanual1

Copyright © 2020 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 1 Matter, Measurement, and Problem Solving

FOLFNKHUHWRGRZQORDG

3

1.22

Prefix multipliers are used with the standard units of measurement to change the value of the unit by powers of 10. For example, the kilometer has the prefix “kilo,” meaning 1000 or103. Therefore 1 kilometer = 1000 meters = 103 meters Similarly, the millimeter has the prefix “milli,” meaning 0.001 or10-3. 1 millimeter = 0.001meters = 10-3 meters

1.23

A derived unit is a combination of other units. Examples of derived units include speed in meters per second (m/s), volume in meters cubed(m3), and density in grams per cubic centimeter(g > cm3).

1.24

The density (d ) of a substance is the ratio of its mass (m) to its volume (V): Mass m Density = or d = Volume V The density of a substance is an example of an intensive property: one that is independent of the amount of the substance. Mass is one of the properties used to calculate the density of a substance. Mass, in contrast to density, is an extensive property: one that depends on the amount of the substance.

1.25

An intensive property is a property that is independent of the amount of the substance. An extensive property is a property that depends on the amount of the substance.

1.26

Measured quantities are reported so that the number of digits reflects the uncertainty in the measurement. The non-place-holding digits in a reported number are called significant figures.

1.27

In multiplication or division, the result carries the same number of significant figures as the factor with the fewest significant figures.

...

Similar Free PDFs

Popular Institutions

- Tinajero National High School - Annex

- Politeknik Caltex Riau

- Yokohama City University

- SGT University

- University of Al-Qadisiyah

- Divine Word College of Vigan

- Techniek College Rotterdam

- Universidade de Santiago

- Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Johor Kampus Pasir Gudang

- Poltekkes Kemenkes Yogyakarta

- Baguio City National High School

- Colegio san marcos

- preparatoria uno

- Centro de Bachillerato Tecnológico Industrial y de Servicios No. 107

- Dalian Maritime University

- Quang Trung Secondary School

- Colegio Tecnológico en Informática

- Corporación Regional de Educación Superior

- Grupo CEDVA

- Dar Al Uloom University

- Centro de Estudios Preuniversitarios de la Universidad Nacional de Ingeniería

- 上智大学

- Aakash International School, Nuna Majara

- San Felipe Neri Catholic School

- Kang Chiao International School - New Taipei City

- Misamis Occidental National High School

- Institución Educativa Escuela Normal Juan Ladrilleros

- Kolehiyo ng Pantukan

- Batanes State College

- Instituto Continental

- Sekolah Menengah Kejuruan Kesehatan Kaltara (Tarakan)

- Colegio de La Inmaculada Concepcion - Cebu