Assessment of critically ill using Abcde Approach PDF

| Title | Assessment of critically ill using Abcde Approach |

|---|---|

| Author | Mehtab Kruckouran |

| Course | Quality + Safety: Nursing Practice 2 |

| Institution | Deakin University |

| Pages | 5 |

| File Size | 183.3 KB |

| File Type | |

| Total Downloads | 9 |

| Total Views | 157 |

Summary

PRACTICE NOTES...

Description

Clinical

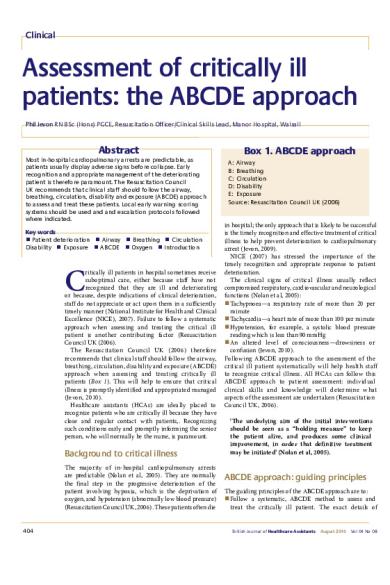

Assessment of critically ill patients: the ABCDE approach Phil Jevon RN BSc (Hons) PGCE, Resuscitation Officer/Clinical Skills Lead, Manor Hospital, Walsall

Abstract Most in-hospital cardiopulmonary arrests are predictable, as patients usually display adverse signs before collapse. Early recognition and appropriate management of the deteriorating patient is therefore paramount. The Resuscitation Council UK recommends that clinical staff should follow the airway, breathing, circulation, disability and exposure (ABCDE) approach to assess and treat these patients. Local early warning scoring systems should be used and and escalation protocols followed where indicated. Key words n Patient deterioration n Airway n Breathing n Circulation Disability n Exposure n ABCDE n Oxygen n Introduction

C

ritically ill patients in hospital sometimes receive suboptimal care, either because staff have not recognized that they are ill and deteriorating or because, despite indications of clinical deterioration, staff do not appreciate or act upon them in a sufficiently timely manner (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), 2007). Failure to follow a systematic approach when assessing and treating the critical ill patient is another contributing factor (Resuscitation Council UK (2006). The Resuscitation Council UK (2006) therefore recommends that clinical staff should follow the airway, breathing, circulation, disability and exposure (ABCDE) approach when assessing and treating critically ill patients ( Box 1). This will help to ensure that critical illness is promptly identified and appropriated managed (Jevon, 2010). Healthcare assistants (HCAs) are ideally placed to recognize patients who are critically ill because they have close and regular contact with patients,. Recognizing such conditions early and promptly informing the senior person, who will normally be the nurse, is paramount.

Background to critical illness The majority of in-hospital cardiopulmonary arrests are predictable (Nolan et al, 2005). They are normally the final step in the progressive deterioration of the patient involving hypoxia, which is the deprivation of oxygen, and hypotension (abnormally low blood pressure) (Resuscitation Council UK, 2006). These patients often die

404

Box 1. ABCDE approach A: Airway B: Breathing C: Circulation D: Disability E: Exposure Source: Resuscitation Council UK (2006)

in hospital; the only approach that is likely to be successful is the timely recognition and effective treatment of critical illness to help prevent deterioration to cardiopulmonary arrest (Jevon, 2009). NICE (2007) has stressed the importance of the timely recognition and appropriate response to patient deterioration. The clinical signs of critical illness usually reflect compromised respiratory, cardiovascular and neurological functions (Nolan et al, 2005): n Tachypnoea—a respiratory rate of more than 20 per minute n Tachycardia—a heart rate of more than 100 per minute n Hypotension, for example, a systolic blood pressure reading which is less than90 mmHg n An altered level of consciousness—drowsiness or confusion (Jevon, 2010). Following ABCDE approach to the assessment of the critical ill patient systematically will help health staff to recognize critical illness. All HCAs can follow this ABCDE approach to patient assessment: individual clinical skills and knowledge will determine what aspects of the assessment are undertaken (Resuscitation Council UK, 2006). ‘The underlying aim of the initial interventions should be seen as a “holding measure” to keep the patient alive, and produces some clinical improvement, in order that definitive treatment may be initiated’ (Nolan et al, 2005).

ABCDE approach: guiding principles The guiding principles of the ABCDE approach are to: n Follow a systematic, ABCDE method to assess and treat the critically ill patient. The exact details of

British Journal of Healthcare Assistants

August 2010

Vol 04 No 08

Clinical this approach will depend on the practitioner’s skills, knowledge and expertise n Undertake a complete initial assessment, re-assessing regularly. If life-threatening problems are identified, they should be treated first before moving on to the next part of assessment n Evaluate the effects of interventions or treatment n Recognize when more senior or additional help is warranted. Any requests for help should be timely and appropriate n Communicate effectively with the person in charge (Resuscitation Council UK, 2006; Jevon, 2009). It is important to note that if the patient is unresponsive and appears to be lifeless, health staff should call for help, check the airway, breathing and circulation (ABC) and start cardiopulmonary respiration (CPR) if necessary.

Airway

Take steps, such as hand washing, to minimize the risk of cross infection. Ensure the environment around the patient is safe. If necessary, remove any hazards or obstacles hindering access to the patient, for example, bedside tables.

Assess the airway. If the patient is talking, he or she will have a patent airway. In partial obstruction, air entry is diminished and often noisy. In complete airway obstruction, there are no breath sounds at the mouth or nose. Look for the signs of airway obstruction. Airway obstruction can result in paradoxical chest and abdominal movements, which is referred to as a ‘see-saw’ respiratory pattern, and the use of the accessory muscles of respiration. Central cyanosis, or blue colouration of the skin, is a late sign of airway obstruction (Jevon, 2008). Listen for signs of airway obstruction. Noisy breathing indicates partial airway obstruction. The character of the noise provides an indication to the location and cause of the obstruction: n Gurgling—fluid, for example, vomit or secretions, present in the mouth or upper airway n Snoring:—displaced tongue partially obstructing the pharynx n Inspiratory stridor—a high-pitched sound on inspiration because of a partial upper airway obstruction, for example, a foreign body or laryngeal oedema(the swelling of the throat) n Expiratory wheeze: a noisy, musical sound caused by turbulent flow of air through narrowed bronchi and bronchioles, more pronounced on expiration. Causes include asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD) (Smith, 2003; Jevon, 2008).

Simple questioning

Treatment of airway obstruction

Ask the patient a simple question and evaluate the response or lack of it. For example: n A normal verbal response implies that the patient has a clear airway, is breathing and has good blood flow to the brain, which is also referred to as adequate cerebral perfusion n An inappropriate response may indicate that the patient is confused, which could be an adverse sign n A breathless patient who can only talk in short sentences is suggestive of profound respiratory distress n Failure to respond is a clear indicator of serious illness (Resuscitation Council UK, 2006; Jevon, 2009). It is important to note that if the patient is unresponsive or responds inappropriately, for example, he or she appears confused, HCAs should ask for help from colleagues.

Begin by assessing whether senior expert help is required. If there is airway obstruction, treat appropriately depending on the cause. Simple interventions, for example, suction or lateral positions are often effective. If the patient is unconscious the oropharyngeal airway, which is between the soft palate and the upper edge of the epiglottis, can be helpful. If the level of the patient’s consciousness has altered, a nasopharyngeal airway, which is behind and above the soft palate, may be helpful. If necessary and if trained to do so, administer oxygen following the instructions of the senior nurse or doctor.

Initial approach to patient assessment The initial approach includes ensuring safety, talking to the patient, observing him or her and monitoring vital signs.

Safety

General appearance Note the patient’s general appearance, for example, is his or her colour pink, pale or blue? Note also whether he or she appears comfortable, distressed, content or concerned (Jevon, 2008).

Vital signs monitoring If trained to do so, attach vital signs monitoring as appropriate, such as pulse oximetry, electrocardiography (ECG) monitoring and continuous, non-invasive blood pressure monitoring, as soon as possible (Resuscitation Council UK, 2006).

British Journal of Healthcare Assistants

August 2010

Vol 04 No 08

Breathing Look for the general signs of respiratory distress (Jevon, 2010), for example: n An anxious appearance n Tachypnoea n Sweating n Pallor or cyanosis n Use of accessory muscles of respiration n Abdominal breathing n The need to be in an upright position to breathe. Count the respiratory rate over 1 minute. The normal respiratory rate in adults is approximately 12–20perminute (Resuscitation Council UK, 2006). Tachypnoea usually indicates illness, patient deterioration or both (Jevon, 2010) and is often one of the first indicators that the patient

405

Clinical is struggling to breathe (Smith, 2003). If the respiratory rate is fast or rising, this suggests that the patient is ill and may suddenly start to deteriorate (Resuscitation Council UK, 2006). Bradypnoea, which is a respiratory rate of less than 12 per minute, may be a normal finding, for example, during sleep, but could be an adverse sign, such as following a head injury or administration of certain drugs such as an opiate. Evaluate the depth of breathing. Deep rapid respirations may be associated with metabolic acidosis, which is the presence of excessive acid in body fluids for example, ketoacidosis, which is caused by high concentration of ketone bodies, the by-products from when fatty acids are broken down. This pattern of breathing is sometimes referred to as Kussmaul’s breathing or air hunger (Jevon, 2008). Shallow respirations may be associated with opiate toxicity. Ascertain whether the chest is moving equally on both sides. If only one side of the chest is moving, this suggests unilateral disease, such as pneumothorax, which is the collection of air or gas in the pleural cavity between the lungs and chest wall, pneumonia and pleural effusion, which is excessive fluid in the fluid in the same place (Smith, 2003). Observe the pattern or rhythm of breathing, for example, Cheyne-Stokes breathing is characterized by periods of apnoea alternating with periods of hyperpnoea (Jevon, 2010). Causes include brain stem ischaemia, which is insufficient blood flow to the brain, cerebral injury, severe left ventricular failure and altered carbon dioxide sensitivity of the respiratory centre (Ford et al, 2005). Note if the patient has a chest deformity, as this could increase the risk of deterioration in the patient’s ability to breathe normally (Resuscitation Council UK, 2006). Observe the peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO 2) reading, which is usually considered to be normal at 95–100%. A low SpO 2 could indicate respiratory distress (Jevon, 2010). If the patient has a chest drain, check it is patent and functioning properly. Listen to the patient’s breathing. Normal breathing is quiet. Abnormal sounds that can be associated with breathing include rattling airway noises, which indicate secretions in the airways, often because the patient cannot cough sufficiently or cannot breath in deeply (Smith, 2003).

Stridor breathing or wheezing suggests partial airway obstruction (Jevon, 2010).

Treatment of compromised breathing Again, assess whether senior expert help is required. Ensure the patient has a clear airway and preferably help the patient in an upright position. When necessary, administer oxygen following the instructions of the senior nurse or doctor, if trained to do so.

Circulation Look at the colour of the patient’s skin. Signs of cardiovascular compromise include pallor and cyanosis. Look for other signs of a poor cardiac output, for example, a decreased level of consciousness or oliguria (reduced output of urine) (Smith, 2003). Look for signs of external haemorrhage from wounds or drains and evidence of internal haemorrhage. Concealed blood loss can be significant, even if drains are empty (Smith, 2003). Palpate the radial pulse, assessing for rate, quality and rhythm. A thready pulse, which is fine and almost imperceptible, is suggestive of poor cardiac output, while a bounding pulse is suggestive of sepsis (Resuscitation Council UK, 2006). Measure the capillary refill time (CRT). Apply pressure to a fingertip, held at the level of the heart, for 5seconds so that the skin becomes blanched and then release. Measure how long it takes for the colour to return. The normal capillary refill time is less than 2seconds. A CRT that is greater than 2seconds indicates reduced skin perfusion, which may indicate the presence of circulatory shock, though other factors such as cool ambient temperature, poor lighting and old age, can also cause a prolonged CRT (Resuscitation Council UK, 2006). When appropriate, begin ECG monitoring if trained to do so. A 12–leadECG (monitoring the output from 12 pairs of electrodes) may needed. Record the blood pressure (BP). A low systolic BP suggests circulatory shock. Assess skin temperature. Cool peripheries suggest poor peripheral perfusion* (the passage of blood through the body) and could indicate circulatory shock, often referred to simply as shock.

WRITE TO US If you have comments on the journal, please contact: [email protected]

www.healthcare-assistants.com

406

British Journal of Healthcare Assistants

August 2010

Vol 04 No 08

Clinical

Key Points

Box 2. AVPU scale

n Most in-hospital cardiopulmonary arrests are predictable.

A: Alert V: Responds to vocal stimuli P: Responds only to painful stimuli U Unresponsive to all stimuli Source: Resuscitation Council UK (2006)

n Early recognition and effective management of the deteriorating patient is paramount. n The clinical signs of critical illness are typically tachypnoea, tachycardia, hypotension and altered level of consciousness.

Treatment of compromised circulation Assess whether senior expert help is required. The specific treatment required for compromised circulation depends on the cause, for example, if the patient is in shock, a large bore cannula (12–14 g) will be inserted to deliver an IV fluid therapy. When necessary, administer oxygen following the instructions of the senior nurse or doctor if trained to do so. The immediate initial treatment for a patient with chest pain is usually a combination of oxygen, aspirin, sublingual glyceryl trinitrate and morphine (Resuscitation Council UK (2006).

n The patient should be assessed and treated following the ABCDE approach.

cause of the altered level of consciousness will be treated if possible, for example, if the patient is hypoglycaemic, glucose will be administered. When necessary, administer oxygen following the instructions of the senior nurse or doctor if trained to do so (Resusitation Council UK (2006).

Exposure Disability Assessment of disability involves evaluating central nervous system function (Resuscitation Council UK, 2006). Assess the patient’s level of consciousness using the AVPU scale (Box2): n Talk to the patient. If he or she is alert, fully awake and talking, he or she is classified as A on the AVPU scale. If the patient responds, but appears confused, attempt to determine whether it is a new or a long-standing problem. Causes of recent onset confusion include a stroke and hypoglycemia, (lower than normal blood glucose) (Jevon, 2008). n If the patient is not fully awake, establish whether he or she responds to a voice, for example, by opening his or her eyes, speaking or moving. It may be necessary to gently shake his or her shoulders and call out the patient’s `name. If he or she responds, a classification of V on the AVPU scale would be given. n If the patient does not respond to voice, administer a central painful stimulus, such as gently rubbing the sternum or breastbone. Observe if there is a response, such as the opening of the eyes; a verbal response, for example, moaning; or a motor response, for example, a movement. If he or she responds to the painful stimulus, the classification is P on the AVPU scale. If he patient does not respond, the classification is U(Jevon, 2010a). n If the patient has an altered level of consciousness, it is usual practice to undertake bedside glucose measurement to exclude hypoglycaemia. The size, equality and reaction to light of the pupils are also usually examined (Resuscitation Council UK, 2006).

Treatment of altered conscious level As before, always assess whether senior expert help is required. The patient will normally need to be nursed in the lateral position to minimize the risk to the airway. The

British Journal of Healthcare Assistants

August 2010

Vol 04 No 08

It may be necessary to undress the patient, taking care to maintain his or her dignity and to avoid hypothermia, in order to undertake a thorough examination and ensure important details are not overlooked (Smith, 2003). In particular, the examination should concentrate on the part of the body that is most likely contributing to the patient’s critical ill status, for example, in suspected anaphylaxis, (a severe allergic reaction), observe the skin for urticaria, which (a type of skin rash) (Jevon, 2008).

Early Warning Signs (EWS) chart It is important to complete the EWS chart as appropriate. Ensure that escalation protocols are followed as required by local policy.

Conclusion The Resuscitation Council UK (2006) recommends that clinical staff should follow the ABCDE approach when assessing and treating critically ill patients. HCAs should follow the systematic approach to patient assessment described here in detail throughout. The importance of BJHCA calling for help early is emphasized. Ford M, Hennessey I, Japp A(2005) Introduction to clinical examination Elsevier, Oxford Jevon P (2008) Clinical Examination Skills. Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford Jevon P (2009) Advanced Cardiac Life Support. 2nd edn. Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford Jevon P (2010) How to ensure patient observations lead to prompt identification of tachypnoea. Nursing Times 106(2): 12–14 NICE (2007) Acutely ill patients in hospital: recognition of and response to acute illness in adults in hospital. NICE, London Nolan J, Deakin C, Soar J et al (2005) European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2005: Section 4. Adult advanced life support. Resuscitation 675S: S39–S86 Resuscitation Council (UK) (2006) Advanced Life Support. 5th edn. Resuscitation Council UK, London Smith G (2003) ALERT Acute Life-Threatening Events Recognition and Treatment. 2nd edn. University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth

407

Copyright of British Journal of Healthcare Assistants is the property of Mark Allen Publishing Ltd and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use....

Similar Free PDFs

Critically Ill HESI Study Guide

- 68 Pages

ABCDE Assessment

- 9 Pages

Tutorial work - ABCDE approach

- 74 Pages

Assignment 2 - ABCDE Assessment

- 15 Pages

Abcde

- 36 Pages

MPLS-Vs-ILL - rjrkkrkr

- 3 Pages

valoració ABCDE

- 5 Pages

Popular Institutions

- Tinajero National High School - Annex

- Politeknik Caltex Riau

- Yokohama City University

- SGT University

- University of Al-Qadisiyah

- Divine Word College of Vigan

- Techniek College Rotterdam

- Universidade de Santiago

- Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Johor Kampus Pasir Gudang

- Poltekkes Kemenkes Yogyakarta

- Baguio City National High School

- Colegio san marcos

- preparatoria uno

- Centro de Bachillerato Tecnológico Industrial y de Servicios No. 107

- Dalian Maritime University

- Quang Trung Secondary School

- Colegio Tecnológico en Informática

- Corporación Regional de Educación Superior

- Grupo CEDVA

- Dar Al Uloom University

- Centro de Estudios Preuniversitarios de la Universidad Nacional de Ingeniería

- 上智大学

- Aakash International School, Nuna Majara

- San Felipe Neri Catholic School

- Kang Chiao International School - New Taipei City

- Misamis Occidental National High School

- Institución Educativa Escuela Normal Juan Ladrilleros

- Kolehiyo ng Pantukan

- Batanes State College

- Instituto Continental

- Sekolah Menengah Kejuruan Kesehatan Kaltara (Tarakan)

- Colegio de La Inmaculada Concepcion - Cebu