Negative pledge clause PDF

| Title | Negative pledge clause |

|---|---|

| Course | Partnership and Company Law II |

| Institution | Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia |

| Pages | 7 |

| File Size | 206.3 KB |

| File Type | |

| Total Downloads | 85 |

| Total Views | 141 |

Summary

Download Negative pledge clause PDF

Description

Question 3: Do you agree that floating charge weakness as a form of security can be offset by the use of a negative pledge for the creation of subsequent charges with more or equal preference and automatic crystallization of default cases?

Answer: According to Section 2 of Companies Act 2016, charge refers to includes a mortgage and any agreement to give or execute a charge or mortgage whether upon demand or otherwise. In the Malaysian law, almost anything of monetary value can be taken as security but the problem is with the acceptance by the financier. Charges under the Companies Act 2016 must be registered within 30 days from the creation of charge. This is stated under Section 352(1) of Companies Act 2016. The contravention of this section will cause the charge to be void as mentioned in Section 352 (2) of the Act.

A floating charge is a security given by a company to a chargee to secure payment obligations. It acts as a security to the dealings made by the company and usually incorporated in a debenture. A floating charge is commonly created over a range of tangible and intangible assets such as stock in trade, raw materials, goods in manufacture, cash in hand, book debts and shares. Normally, the charge would cover the entire business of the company. In Re Yorkshire Woolcombers1, Romer LJ outlined three characteristics to determine a floating charge. First, it is a floating charge when there is a charge on a class of assets both present and future. Second, that class is one which in the ordinary course of the business of the company would be changing from time to time. Third, when it is contemplated by the charge that, until some future step is taken by or on behalf of the mortgagee, the company may carry on its business in the ordinary way so far as concerns the particular class of assets charged. By its nature, the floating charge will include future assets that do not exist at the time the charge is created. In Companies Act 2016, a floating charge is listed as a charge that requires under Section 353 (g).

Due to the disadvantages and risk of the unrestrained dealings associated with a floating charge, a lender has resorted ways to protect itself. The lender may require 1 [1903] 2 Ch 284, 295.

crystallisation of floating charge to be fixed charge. Crystallisation is the conversion of a floating charge into a fixed charge over any assets given as security on the occurrence of certain events. There are few circumstances where crystallisation could take effect. However, all of these are depends on the negotiation between the lenders and the company, which is the chargor and chargee. The charge document will state out all the circumstances where the crystallisation may take effect.

First, crystallisation could be happened when default in the repayment of the loan by the company. The case of NGV Tech Sdn Bhd (appointed reciever and manager) (in liquidation) & Anor v Kerajaan Malaysia [2017] illustrated that a notice of crystallisation of the floating charge was issued to the plaintiff and a receiver was appointed by Maybank due to the default in payments of the loan. Second, when there is breach of covenants in the charge document, for example, breach of restriction to create further encumbrances on the company’s assets or breach of restrictions on borrowing. This could be substanciated when there is a negative pledge clause in the charge document which restrict subsequent charge. Third, the lenders may crystallise the floating charge when the value of assets have declined to a certain amount. This is one of the weakness of floating charge where the company may continue deal in and dispose all the assets that are subject to floating charge, hence the lenders may face the risk of dissipation of the assets and could not recover back the debt from the company. Fourth, when other creditors have instituted proceedings against the company, such as execution proceedings. Evans v Rival Granite Quarries Ltd [1910] highlighted that in the event of floating charge, the judgement creditor will have the priority over the proceeds from the sale of the stock in trade unless the floating charge was crystallised before the completion of the execution proceedings. Fifth, in the event that the company ceases to carry on business or winding up, the floating charge can be crystallised. This has been proved in the case of Re Woodroffes (Musical Instruments) Ltd[1985] where the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank had the right to convert the floating charge into fixed charge on the assets specified in the notice when the company stop to carry on the business. Besides, United Malayan Building Corp Bhd v Official Receiver and Liquidator of Soon Hup Seng Sdn Bhd[1986] illustrated that the floating charge can be crystallised when a receiver or manager, which known as liquidator is appointed. This was also being strengthen in the case of Teoh Vin Sen v True Creation Sdn Bhd [2008] where the floating charge been crystallised when the petition to wind up the company is filed in court.

In the above scenarios, all the crystallisation process may be happened in two ways, which is crystallisation upon service of notice to company and the other one is automatic crystallisation. For the method of crystallisation upon service of notice, the floating charge can be crystallised only upon notice from the lender to the company. Pending the notice, the company has the freedom to deal with the said assets. There is the recent drafting innovation in floating charge and most of the lenders may include the automatic crystallisation clause in the charge document. As per Buckley LJ in Evans v Rival Granite Quarries Ltd [1910] stated that a floating charge is not a future security; it is a present security which presently affects all the assets of the company expressed to be included in it. For an automatic crystallisation clause to be effective, the language in the charge document must clearly specify that the floating charge is to crystallise immediately and without any intervention by the debenture holder as a result of the occurrence of the automatic crystallisation events.According to Re Panama, NZ & Australian Royal Mail Co and UMBC Bhd v Official Receiver Of Soon Hup Seng, there will be automatic crystallization if a receiver was appointed by the court or creditor under a debenture. Upon the occurrence of such an event, the floating charge then crystallizes and the security interest of the debenture holder is said to attach to the charged assets and the charge becomes a fixed charge. Hence, notice from the lender is not necessary for the process of automatic crystallisation. By looking at this context, crystallisation of floating charge to fixed charge is one of the ways to offset the weakness of the floating charge as security.

The difficulty with the cases relied on by those who reject automatic crystallisation is to determine to what extent particular decisions rely on the inherent nature of a floating charge, as distinct from the implied intentions of the contracting party. This can be seen through the England case. In the Manila Railway case, Lord Halsbury L. C., in deciding that the charge would not automatically crystallise, was content to rely on the intention of the parties. Lord Nacnaghten agreed that a debenture holder's right to intervene might be suspended by agreement. But in relation to crystallisation, His Lordship felt it was in the nature of the agreement that it continue to float until a cessation of business or until the debenture holders intervened. According to Roy Goode in Goode on Legal Problems of Credit and Security, clauses that merely empower a debenture holder to intervene are not sufficient to crystallise a floating charge in the absence of actual intervention. It has been said that the debenture holder’s act of intervention must satisfy a threefold test; (1) it must be done

with the intention of converting a charge into a fixed charge; (2) it must be authorised by the express or implied terms of the debenture; and (3) it must divest the company of de jure control of the assets.

Apart from the method of crystallisation, since floating charge is a charge that does not attach to the assets. Hence, the company may continue to deal with the charged assets in its ordinary course of business and has the right to sell and to charge the assets as securities for loans. As the company is allowed to deal with the assets in its ordinary course of business, this will allow the company to create a subsequent charge over the charged assets as security for its further borrowings. According to Re Colonial Trusts Corp(1879), if the subsequent charge is a fixed charge, the subsequent charge may have priority over the floating charge.

Hence, negative pledge clause come in as a way to protect the first chargee. Negative pledge clause is designed to address the risk of losing priority encountered by unsecured lenders. The clause imposes on the borrower the duty not to grant security in the charged property to subsequent creditors or to restrict the borrower from using the charged property as security for future loans. In other way, the clause restricts the lender to create any further charges either fixed or floating, over the same assets in favour of another lender unless the company has obtained the prior consent from the first chargee.

The application of negative pledge clause to offset the weakness of floating charge can be seen in the case of Re Connolly Bros Ltd (No 2) [1912], a company issued debentures to lender, creating a floating charge over all its property, present and future, the debenture provided with negative pledge clause that the company was not to be at liberty to grant any other mortgage or charge in priority to the debenture. The court in this case held that the negative pledge clause prohibits all the subsequent charges created by the company without the consent of the lender and hence all the subsequent charges are not valid. Negative pledge clause is binding on the company. The breach of the pledge is a breach of covenant in the charge document which may allow the lender to enforce the charge. Further, if the negative pledge clause is included in the particulars of the charge to be lodged with the Registrar of Company (ROC), the public which includes any subsequent chargee, will be deemed to have constructive notice as stated in Section 39 CA 2016. Section 352(1) also requires the company to lodge with ROC a statement on the particular of the charge within 30 days from the creation of the charge. While Section 362 requires the company to keep a copy of

instrument creating the charge at the company’s registered office. Therefore, when there is a dispute on the negative pledge clause, it can be argued that the subsequent lender had constructive notice of the negative pledge clause and did not take its charge in good faith upon the lodgement of charge particulars with ROC.

However, negative pledge clause brings its limitation. It is only binding between the company and the debenture holder as contractual covenants; not binding on the subsequent third party such a clause is binding between the company and the debenture-holder. Such restrictive clauses have not had the desired effect in certain circumstances. In the British case, Re Castell & Brown, Ltd (1898), a company issued a series of debentures secured by a floating charge over all its present and future properties. The debentures provided that the company was not to be at liberty to create any mortgage of charge upon its freehold or leasehold hereditaments in priority to the debentures. The title deeds of various properties, which had been left in the possession of the company, were later deposited with the company’s bank to secure and overdraft. When this charge was given, the bank had no notice of the existence of the debentures and made no inquiries. The bank’s charge was held to have priority over the earlier debentures. The decision was deemed to be as follow the decision of Court of appeal in previous case, English & Scottish Mercantile Investment Co v Brunton(1982), which have the similar fact with Re Castell. The principle lied down in English & Scottish Mercantile Investment Co v Brunton was followed in Re Valletort Sanitary Steam Laundry Co Ltd (1903). In short, even when the negative pledge clause is breached, a later chargee will be able to enforce the charge if he took it for value and without notice of the pledge. The later chargee will only be bound by the pledge if he had actual knowledge of it.

Despite the floating charge having a restrictive clause, this information was absent from the register as it was not a prescribed particular to be registered. What is more, there was a subsequent specific chargee that claimed priority over the floating charge. This was indeed the case in Re Standard Rotary Machine Co. Ltd. It is to be taken into account that the floating charge at the time was registered under the Companies Act 1900. It was found in this case that although there was constructive notice on the Registration of the floating charge, this does not amount to a constructive notice of the restrictive clause that comes with the floating charge as it is not registered together with the registration of the charge. This decision was followed in Wilson v Kelland where the subsequent specific chargee had no

actual notice of any restrictive clause in the registered floating charge. Eve J deduced that it was not upon the subsequent chargee to investigate the nature of any prior floating charge. It was again similarly decided in G & T Earle Ltd v Hemsworth RDC that the plaintiff was not construed to have constructive notice regarding the actual terms of debentures (restrictive condition) despite having constructive notice on the existence of it. Regardless of the fact that it was common practice for debentures to contain limiting conditions, this still was not enough to amount to a form of constructive notice of the terms of the debentures.

In order of a negative pledge as a form of constructive notice to be valid, the notice of the existence of the prior floating charge is not sufficient. There must be notice of the clause itself.

This position from the England case, Wilson v Kelland (1910) was upheld by

Malaysian Court in United Malayan Banking Corp Bhd v Aluminex (M) Sdn Bhd (1993). The supreme Court holding that notice of a debenture creating a floating charge does not constitute notice of the terms thereof, including restrictive clauses forbidding the creation of later charges ranking in priority to or pari passu with the charge containing the clause. The Supreme Court also highlighted that the procedure in force at that material time for registration of a debenture did not require a record to be made of the particulars of a restrictive clause. Obviously, restrictive clause was not one of the prescribed particulars to be disclosed for the purpose of registration of a charge. The Supreme Court’s decision in the Aluminex’s case was based on this unamend version of Form 34. The limitation of this constructive notice as mentioned in the case above lead to the argument that negative pledge cannot strengthen the weakness of floating charge.

The question arises as to whether the contents of Form 34, in which item 7 states that the creation of subsequent charge is restricted or prohibited, can amount to constructive notice to a subsequent chargee. There is still open to argument whether the chargee has the priority of the subsequent charge. It is yet to be seen whether the requirement for the holder of the fixed charge to have actual notice of the negative clause pledge clause is still required by looking at the new provision of Section 39 which imputes knowledge upon the lodgement of charge. However, infringement of negative pledge clause that will give rise to a cause of action may be a consolation to the holder of floating charge who find his security postponed to a subsequent chargee. As upon a breach of such clause, the creditor is entitled to enforce the floating charge which will have crystallised upon the intervention of the creditor. This somehow can be used

to improve the position of floating charge as a security. Therefore, in our opinion, negative pledge and automatic crystallisation clause are sufficient enough to offset the weakness of floating charge as a form of security....

Similar Free PDFs

Negative pledge clause

- 7 Pages

Adverb clause

- 15 Pages

Mortgage-and-pledge cases

- 4 Pages

Ouster Clause - ---

- 6 Pages

Nurses Prayer AND Pledge

- 1 Pages

Contract clause examples

- 2 Pages

Pledge (Credit Transaction)

- 10 Pages

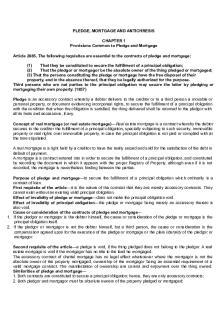

Pledge, Mortgage AND Antichresis

- 17 Pages

Bailment and pledge

- 26 Pages

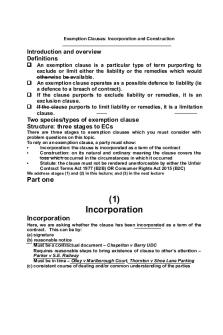

Exclusion Clause cases

- 2 Pages

Phrase, Clause, Sentence types

- 26 Pages

Phrase, Clause AND Sentence

- 8 Pages

Exclusion clause lecture

- 14 Pages

Exemption Clause part 1

- 7 Pages

Exclusion clause note

- 12 Pages

Popular Institutions

- Tinajero National High School - Annex

- Politeknik Caltex Riau

- Yokohama City University

- SGT University

- University of Al-Qadisiyah

- Divine Word College of Vigan

- Techniek College Rotterdam

- Universidade de Santiago

- Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Johor Kampus Pasir Gudang

- Poltekkes Kemenkes Yogyakarta

- Baguio City National High School

- Colegio san marcos

- preparatoria uno

- Centro de Bachillerato Tecnológico Industrial y de Servicios No. 107

- Dalian Maritime University

- Quang Trung Secondary School

- Colegio Tecnológico en Informática

- Corporación Regional de Educación Superior

- Grupo CEDVA

- Dar Al Uloom University

- Centro de Estudios Preuniversitarios de la Universidad Nacional de Ingeniería

- 上智大学

- Aakash International School, Nuna Majara

- San Felipe Neri Catholic School

- Kang Chiao International School - New Taipei City

- Misamis Occidental National High School

- Institución Educativa Escuela Normal Juan Ladrilleros

- Kolehiyo ng Pantukan

- Batanes State College

- Instituto Continental

- Sekolah Menengah Kejuruan Kesehatan Kaltara (Tarakan)

- Colegio de La Inmaculada Concepcion - Cebu