Ouster Clause - --- PDF

| Title | Ouster Clause - --- |

|---|---|

| Author | 无名 之辈 |

| Course | Administrative Law |

| Institution | Multimedia University |

| Pages | 6 |

| File Size | 139.3 KB |

| File Type | |

| Total Downloads | 20 |

| Total Views | 138 |

Summary

---...

Description

Ouster Clause Definition of Ouster Clauses The statement refers to the right to judicial review if the decision of the public authority aggravates an individual. There is, however, an exception to the ouster clause. Ouster Clause is a provision or clause which is inserted in a law to prohibit court judicial review of a specific matter outside the jurisdiction of the court. A clause or a privative clause is a clause or a provision that a legislative body includes in a piece of legislation to prevent judicial review of executive acts or decisions by removing their supervisory judicial functions from the courts. This will favour public bodies as a judicial review will be avoided if an ouster provision exists. The judicial review by the court with the Parliament 's authority allows the validity of the decision-making process for public authorities to be called into question. This is proof of acceptance of the rule of law and separation of power. Two types of ouster clauses exist, that is, total and partial. The total or finality provision removes the supervisory jurisdiction of courts absolutely. The partial ouster clause provides a time period within which a remedy is required and no relief will be given beyond the time limit. However, the authorities have been found to act in bad faith, and then, even though there is a time lapse in time, the authorities are subject to judicial review. If the final decision is deemed illegal, the courts may escape from the ouster clause and perform judicial review. Examples of Ouster Clause can be seen in several section. Section 4(4) of the Foreign Compensation Act stated that the Commission shall not call into question, in any court of law, the decision of any application made to them under this Act. S. 9(6) Industrial Relations Act 1967 provides that the Minister 's decision referred to in paragraph (1D) or (5) is final and not in any court of law is to be challenged. S. 33B (1) of the Industrial Relations Act 1967 stated that the Court's award, judgment or orders under this Act (even the Court's decision whether or not to approve an application under subsection 33A(1) is definitive and conclusive, and is not challenged, appealed, reviewed, quashed or brought in any case. S. 59A(1) Immigration Act 1959/63 provides that any act done by the Minister or the Director General, or in the case of an East Malaysian State, the State Authority, in any court, or any decision taken under that law , shall not be subject to judicial review unless there are issues concerning compliance with any procedural requirement of that Act or regulations regulating that act or decision. This Act shall apply to all matters. While the section prima facie does not provide for judicial review, the section acknowledges situations where such a review can be necessary.

English Position The exercise of supervisory authority is supposed to be restricted or omitted in English position. In the earlier era these rules were only disregarded by the English courts when the judgments of the bodies were caused by a jurisdictional error. The court has explained that

the ouster clauses do not preclude courts from having to deal both with jurisdictional and non-jurisdictional errors following the case of Anisminic. The law distinguishes between circumstances in which the public body functions as part of the law imposed upon it but makes an error of law known as a "non-jurisdictional error of law" and circumstances in which the execution of the error of law means that the public body does not necessarily have the capacity to act as a "jurisdictional error of law". In the first instance, an ouster provision prohibited courts from carrying out their supervisory role and from making any prerogative order that the wrong action could be quashed. For example, if the public body erroneously interpreted the breadth of its powers and thus made a decision which it had no power to make, then the courts could only intervene if the error of law impaired the ability of the public body to intervene. Definition of jurisdictional error by Hayne J saying that the difficulty of drawing a bright line between jurisdictional error and error in the exercise of jurisdiction should not be permitted, however, to obscure the difference that is illustrated by considering clear cases of each species of error. There is a jurisdictional error if the decision maker makes a decision outside the limits of the functions and powers conferred on him or her, or does something which he or she lacks power to do. By contrast, incorrectly deciding something which the decision maker is authorised to decide is an error within jurisdiction. The concept of jurisdictional error has been widely interpreted following the case of Anisminic v Foreign Compensation Commission. In this case, property of A was confiscated by the Egyptian government after the Suez Crisis, which in return paid a sum of money to the British government. FCC was delegated the task of settling the claims. A’s claim was rejected. Thus, A seek declaration. But, the Foreign Compensation Act contains an ouster clause: “determination of the commission shall not be called in question in any court of law.” The judgement by the court was A tribunal may exceed its jurisdiction in the course of enquiry if it took into account matters which it had no right to take into account (error of law), rendering the decision a nullity and, thus, subject to judicial review. Following the abandonment of military equipment in Egypt in 1965, the Foreign Compensation Act 1950 allowed recovery of compensation for items left abandoned. The Foreign Compensation Commission had misinterpreted certain subsidiary legislation, with the effect that almost all claims for foreign compensation would be defeated. Anisminic’s statutory claim for compensation failed. Certiorari was still granted despite an ouster clause. All errors of law are now to be considered as jurisdictional and ultra vires in a broad sense of the term. Implies that ouster clauses should not be effective against any error of law. The House of Lords held that ouster clauses cannot prevent the courts from examining an executive decision that, due to an error of law, is a nullity. Subsequent cases held that Anisminic had abolished the distinction between jurisdictional and non-jurisdictional errors of law. In R. v. Lord President of the Privy Council, ex parte Page, the House of Lords noted that the decision in Anisminic rendered obsolete the distinction between errors of law on the face of the record and other errors of law by extending the doctrine of ultra vires. Thenceforward it was to be taken that Parliament had only conferred the decision-making power on the basis that it was to be exercised on the correct legal basis: a misdirection in law in making the decision therefore rendered the decision ultra vires.

In R v Medical Appeal Tribunal, ex parte Gilmore, the claimant had received two injuries on his eyes and these injuries had resulted in his total blindness. He then sought for an order of cetriorari against the respondent who had found only 20% disability when giving him compensation. The respondent argued that the decision cannot be reviewed as it is provided in Section 36(3) of the National Insurance (Industrial Injuries) Act 1946 that “any decisions of a claim or question … shall be final”. The court then held that it can be reviewed as Lord Denning had interpreted that provision to be effective for appeal but not judicial review. It means that the decision will only be final in an appeal but it is still not be final in a judicial review. Therefore, we can conclude that all errors of law can be reviewed by the courts. In R v Lord President of the Privy Council, ex parte Page , the court had followed the decision made in the Anisminic case and held that all errors of law are reviewable by the courts although it is in the ouster clause. The decision of Anisminic case was also upheld by the Supreme Court in R (on the application of Cart) v Upper Tribunal. The court held that since it is practically immaterial to the victim of an error of law whether it is a jurisdictional error or otherwise, it would be manifestly unjust if judicial review was precluded when a non-jurisdictional error was egregious and obvious, but allowed for a small jurisdictional error In R (Privacy International) v Investigatory Powers Tribunal, Court held that the ouster clause in the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000, which creates the Investigatory Powers Tribunal, suffices to prevent the High Court from carrying out judicial review of that tribunal’s decisions. This decision is unusual in recognising that an ouster clause has that effect. In re Racal Communications Ltd , Lord Diplock consider whether judicial review could lie against a court decision in general. He expressly distinguished Anisminic on the basis that it was dealing with bodies acting in an administrative capacity rather than judicial capacity and claimed that the case created a “presumption” with administrative decisions that where there is any doubt about the question to be answered, the courts must “resolve” it “as interpreters of the written law”. Lord Diplock held that where parliament intended to oust the jurisdiction of the High Court over inferior courts, such clauses should be more generously construed than clauses concerning executive bodies. The reason for the different treatment could simply be the lack of separation of powers implications when considering judicial supervision of courts. In those constitutional circumstances, parliament’s linguistic clarity burden may be considerably diminished.

Malaysian Position Before 1980, the Malaysian position on ouster clauses was not entirely consistent but in no case was a privative clause construed as wide enough to oust judicial review in toto. Ouster clauses could not preclude judicial review on ground of error of law on the face of the record or excess or lack of jurisdiction. Malaysia also widely followed the UK position before the Anisminic case. When determining if a public body is acting within the powers conferred on it by law but committed an error of law which is known as jurisdictional or non-jurisdictional distinction.

In the case of S.E. Asia Fire Bricks v Non-Metallic Mineral Products, the Privy Council held that the privative clause in s.33B(1) of the Industrial Relations Act will not oust certiorari if the inferior tribunal has acted “without jurisdiction” or if it has done or failed to do something in the course of the inquiry which is of such a nature that “its discretion is a nullity”. The Privy Council also stated that the error of law in the case was a nonjurisdictional error which did not allow any judicial intervention. However, some optimism can be seen from Mohamad Azmi’s dicta in Enesty v TWU that "perhaps the time will come for this court to consider the... discarding of the distinction between an error of law which affected jurisdiction and one which did not". Whereby, his dicta came true in the case of Syarikat Kenderaan Melayu Kelantan Bhd. V Transport Workers’ Union. In this case, Gopal Sri Ram stated that an inferior tribunal or other decision-making authority, whether exercising a quasi-judicial function or purely an administrative function, has no jurisdiction to commit an error of law. Henceforth, it is no longer of concern whether the error of law is jurisdictional or not. If an inferior tribunal or other public decision-taker does make such an error, then he exceeded his jurisdiction. So too is jurisdiction exceeded, where resort is had to an unfair procedure, or where the decision reached is unreasonable. He added that It is neither feasible nor desirable to attempt an exhaustive definition of what amounts to an error of law, for the categories of such an error are not closed. But it may be safely said that an error of law would be disclosed if the decision-maker asks himself the wrong question or takes into account irrelevant considerations or omits to take into account relevant considerations (what may be conveniently termed as an Anisminic error) or if he misconstrues the terms of any relevant statute, or misapplies or misstates a principle of the general law. Since an inferior tribunal has no jurisdiction to make an error of law, its decisions will not be immunized from judicial review by an ouster clause however widely drafted. It follows that the decision of the Board in Fire Bricks and all those cases approved by it are no longer good law. The Court of Appeal in Syarikat Kenderaan Melayu Kelantan took a bold step by discarding the distinction between an error of law and an error of jurisdiction which had plagued our law ever since 1980. In Syarikat Kenderaan Melayu Kelantan v Transport Workers Union, it was stated that there was no longer the need to ascertain whether the error committed by the administration is jurisdictional or not. Any error of law, whether jurisdictional or within jurisdiction, becomes reviewable even with an ouster clause. The ruling in SKMK does not have to be confined to the ouster clauses in the Industrial Relations Act only and the scope of judicial review over the decisions of inferior tribunals is now necessarily enlarged. To sum up what this case is saying, any error of law now is reviewable by courts, it is now not relevant anymore to categorize errors of law, the decision is not confined to Industrial Relations Act (applicable to all acts) and the scope of judicial review is now being widen. In the case of Pihak Berkuasa Negeri Sabah v Sugumar Balakrishnan, pihak berkuasa negeri sabah terminate the entry permit of Sugumar to the state of Sabah. Sugumar applied to high court for writ of certiorari of the sabah state government decision to revoke his entry permit to Sabah. Section 59A of the Immigration Act 1963 has an ouster clause and high court decided that s 59A cannot be reviewed because of the ouster clause. Sugumar appeal to

court of appeal. Court of Appeal overruled the high court decision and granted the writ of certiorari that Sugumar asking for. Court of Appeal upheld that ouster clauses are unconstitutional except in cases of national security such as involving ISA or in overriding national interest. The preclusion of the right to judicial review was a violation of Article 5 of FC. Article 5 and Article 8 of FC should be read as widely as possible. Federal Court quash the court of appeal decision. Justice Mohamed deciding that by deliberately spelling out that there shall be no judicial review by the court under act of parliament, or any act or any decision of the minister or decision-maker except for non-compliance of any procedural requirement. Parliament must have intended that the section is conclusive on the exclusion of judicial review under the act. In Tan Teck Seng v Suruhanjaya Perkhidmatan Pendidikan & ors, Gopal Sri Ram decided that Article 5 and Article 8 of Federal Constitution must be interpreted as widely as possible. Mr Tan as a senior assistant of a primary school and he was dismissed by the Suruhanjaya Perkhidmatan Pendidikan without any proper reason. Mr Tan went to court and Court of Appeal held that Article 5 and Article 8 of FC protects personal liberty and equality under the law must be read in a liberal approach and not a literal approach. Gopal Sri Ram said judges should when discharge their duties as interpreters of supreme law adopt a liberal approach in order to implement the true intention of the framers of federal constitution. Such objectives may only be achieved if expression of life in Article 5 is given a broad and liberal meaning. Under broad interpretation of Article 5 his dismissal was wrongful and unconstitutional. In Semenyih Jaya Sdn Bhd v Pentadbir Tanah Daerah Hulu Langat, valuation experts or Assessors cannot usurp the function of the court despite a provision in the Land Acquisition Act 1960 to enable them to have the last say in determining what amounts to adequate compensation under Art 13(2). The Federal Court stressed that the power to award compensation in land reference proceedings is a judicial power that should rightly be exercised by a judge and no other. In R Rama Chandran v The Industrial Court Of Malaysia & Anor , despite the ouster clause of the Industrial Relations Act, it was held that courts can intervene in appropriate cases, “all for the cause of justice”. It was also held that the High Court has the powers to review the decision of the Industrial Court on the merits, to substitute a different decision in place of the Industrial Court Award without remitting the case to the Industrial Court for readjudication, and to order consequential relief, although in Section 33B of the Industrial Relations Act 1967, it provides that an Industrial Court Award is final and shall not be challenged, appealed against, reviewed, quashed or called into question by any court. In Danaharta Urus sdn bhd v Kekatong sdn bhd, S72 of Pengurusan Danaharta Nasional Berhad Act that prohibits the court from issuing an interlocutory injunction to the appellant. Federal court overruled court of appeal decision and referred to the right of access to justice and held that the court had earth in interpreting Article 5(1). Right to access to justice is not automatic, therefore Parliament can include ouster clause in the case to remove your right to court of appeal in court. Parliament can enact a federal law pursuant to the authority conferred by Art. 121(1) to remove the jurisdiction of the court. In the case of Inchcape Malaysia Holdings, the court held that, such a privative or finality cause were to be given a literal interpretation, the results would have been to reduce the

supervisory roles of High Courts to such an extent that a large number of administrative and quasi-judicial authorities would be exercising significant power without any forms of control. In Selva Kumar A/L Tamil Selvom v Timbalan Menteri Dalam Negeri , the applicant filed an application for a writ of habeas corpus, seeking for his release from detention under s 4(1) of the Emergency Ordinance (Public Order and Prevention of Crime) 1969. Once the detention order was made under s 4 of the Ordinance, this court, in view of the ouster clause under s 7C of that Ordinance, was barred from reviewing that order unless it can be shown that there had been non-compliance of any procedural requirement governing such detention....

Similar Free PDFs

Ouster Clause - ---

- 6 Pages

Adverb clause

- 15 Pages

Contract clause examples

- 2 Pages

Exclusion Clause cases

- 2 Pages

Negative pledge clause

- 7 Pages

Phrase, Clause, Sentence types

- 26 Pages

Phrase, Clause AND Sentence

- 8 Pages

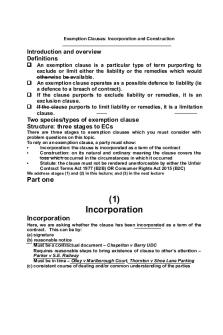

Exclusion clause lecture

- 14 Pages

Exemption Clause part 1

- 7 Pages

Exclusion clause note

- 12 Pages

Extra Notes on Objects Clause

- 1 Pages

Extra Notes on Objects Clause

- 1 Pages

Popular Institutions

- Tinajero National High School - Annex

- Politeknik Caltex Riau

- Yokohama City University

- SGT University

- University of Al-Qadisiyah

- Divine Word College of Vigan

- Techniek College Rotterdam

- Universidade de Santiago

- Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Johor Kampus Pasir Gudang

- Poltekkes Kemenkes Yogyakarta

- Baguio City National High School

- Colegio san marcos

- preparatoria uno

- Centro de Bachillerato Tecnológico Industrial y de Servicios No. 107

- Dalian Maritime University

- Quang Trung Secondary School

- Colegio Tecnológico en Informática

- Corporación Regional de Educación Superior

- Grupo CEDVA

- Dar Al Uloom University

- Centro de Estudios Preuniversitarios de la Universidad Nacional de Ingeniería

- 上智大学

- Aakash International School, Nuna Majara

- San Felipe Neri Catholic School

- Kang Chiao International School - New Taipei City

- Misamis Occidental National High School

- Institución Educativa Escuela Normal Juan Ladrilleros

- Kolehiyo ng Pantukan

- Batanes State College

- Instituto Continental

- Sekolah Menengah Kejuruan Kesehatan Kaltara (Tarakan)

- Colegio de La Inmaculada Concepcion - Cebu