Requirements of a deed UK PDF

| Title | Requirements of a deed UK |

|---|---|

| Author | Rojer Inglis |

| Course | LLM |

| Institution | Unicaf University |

| Pages | 3 |

| File Size | 137 KB |

| File Type | |

| Total Downloads | 87 |

| Total Views | 129 |

Summary

SUMMARIE OF A TOPIC AND CASES RELATED...

Description

Please note that HM Land Registry’s practice guides are aimed primarily at solicitors and other conveyancers. They often deal with complex matters and use legal terms.

1. General points 1.1 The need for a deed when dealing with land With a few exceptions (section 52(2) of the Law of Property Act 1925), a legal interest in land cannot be conveyed or created without a deed (section 52(1) of the Law of Property Act 1925). The exceptions include: • •

assents, which must be in writing but need not be executed as a deed (section 36(4) of the Administration of Estates Act 1925) leases taking effect in possession for a term not exceeding 3 years at the best rent which can be reasonably obtained without taking a fine (section 54(2) of the Law of Property Act 1925)

Section 91 of the Land Registration Act 2002 provides that a document in electronic form purporting to effect a disposition and that meets certain requirements is to be regarded for the purposes of any enactment as a deed. These electronic dispositions are not covered by this practice guide as they are not deeds.

1.2 Elements of a deed To be a deed the document must: • •

•

be in writing make clear on its face that it is intended to be a deed by the person making it or the parties to it. This can be done by the document describing itself as a deed or expressing itself to be executed as a deed ‘or otherwise’ be validly executed as a deed by the person making it or one or more of the parties to it (section 1 of the Law of Property (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1989)

Where a person outside England and Wales, or a company or corporation incorporated outside England and Wales, is to execute a deed relating to land in England and Wales, it is still English law that applies to the form and execution of the deed. Land is ‘immovable property’ and so the law governing its disposition is the law of the territory in which it is situated.

2. Execution of deeds by individuals 2.1 The 3 elements: signature, attestation and delivery 2.1.1 Signature

To be validly executed as a deed, each individual must sign the document. Making one’s mark on a document is treated as signing it (section 1(4) of the Law of Property (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1989). The signature must be on the document itself in the space provided and the words of execution must name the signatory or otherwise make clear who has signed the document. For obvious reasons, the signature ought to be in ink or some other indelible medium. Each individual must sign manually, not in facsimile. However, the registrar might accept a discharge or release in form DS1 or form DS3 though signed in facsimile. A discharge or release in one of these forms must be “executed as a deed or authenticated in such other manner as the registrar may approve” (rule 114(3) of the Land Registration Rules 2003). Note the position with ‘Mercury signing’; see Mercury signatures and Electronic signatures. 2.1.2 Attestation by a witness Each individual must sign “in the presence of a witness who attests the signature” (section 1(3) of the Law of Property (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1989). We look to see that a witness has signed the deed, that their signature clearly records the witnessing of the signing of the deed by each individual concerned, and that the name and address of the witness appear in legible form on the deed. It is important that names and addresses are complete (including any postcode) and legible as this can help in locating and contacting witnesses by any party should any issue arise concerning the execution. The same witness may witness each individual signature, but each signature must be separately attested, unless it is absolutely clear by express wording on the face of the attestation that the witness is witnessing both or all signatures in the presence of the named signatories. Appendix 2 gives some examples of execution where there is only one attesting witness to multiple signatures. A party to the deed cannot witness the signature of another party to the deed (Seal v Claridge (1881) 7 QBD 516 at 519). The relevant legislation does not prevent a signatory’s spouse, civil partner or cohabitee from acting as a witness (if they are not a party to a deed), but this is best avoided. It is also advisable that the witness be no younger than 18 or, at least, of sufficient maturity for their evidence to be relied on should it later prove necessary to verify the circumstances under which the execution took place. The Law Commission report “Electronic execution of documents” (Law Com No 386), published in September 2019, concluded that the requirement under section 1(3) of the Law of Property (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1989 and section 44(2)(b) of the Companies Act 2006 that a deed must be signed “in the presence of a witness” requires the physical presence of that witness, and that this is the case even where both the person executing the deed and the witness are executing and attesting the document using an electronic signature. The Law Commission was not satisfied that the witness’s “virtual” or “remote” presence was sufficient. Accordingly, HM Land Registry continues to require that the witness be actually present when the deed is signed, the witness then adding their signature. However, there is no reason why the witness and signatory cannot be separated by glass, so a signature could be witnessed by someone looking

through a car or house window – if, of course, they were then able to see clearly the signatory signing. 2.1.3 Delivery The document must be “delivered as a deed” by each person executing it or a person authorised to deliver it on their behalf (section 1(3)(b) of the Law of Property (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1989). Delivery requires that the person expressly or impliedly acknowledges, by words or conduct, an intention to be bound by its provisions. Where a conveyancer, in a transaction involving the disposal or creation of an interest in land, purports to deliver a document as a deed on behalf of a party to it, there is a conclusive presumption in favour of a purchaser that the conveyancer is authorised to deliver it (section 1(5) of the Law of Property (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1989). In practice, we assume that a document has been delivered as a deed unless there is some indication to the contrary. So if, for example, the words of execution have been modified to provide that delivery has not taken place, or that delivery is not to be presumed until some condition has been fulfilled, we will require evidence that delivery has subsequently taken place....

Similar Free PDFs

Requirements of a deed UK

- 3 Pages

++ Drafting Parts OF A DEED

- 11 Pages

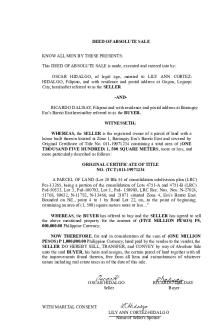

DEED OF ABSOLUTE SALE

- 3 Pages

DEED OF ABSOLUTE SALE.docx

- 2 Pages

Marave - Deed of Absolute Sale

- 3 Pages

User Requirements A Roadmap

- 12 Pages

DEED OF REAL ESTATE MORTGAGE

- 3 Pages

(( Pestle analysis of NHS Uk))

- 3 Pages

Fiqws 10301 Grade A requirements

- 8 Pages

DEED OF Absolute SALE 2 - Law

- 3 Pages

Popular Institutions

- Tinajero National High School - Annex

- Politeknik Caltex Riau

- Yokohama City University

- SGT University

- University of Al-Qadisiyah

- Divine Word College of Vigan

- Techniek College Rotterdam

- Universidade de Santiago

- Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Johor Kampus Pasir Gudang

- Poltekkes Kemenkes Yogyakarta

- Baguio City National High School

- Colegio san marcos

- preparatoria uno

- Centro de Bachillerato Tecnológico Industrial y de Servicios No. 107

- Dalian Maritime University

- Quang Trung Secondary School

- Colegio Tecnológico en Informática

- Corporación Regional de Educación Superior

- Grupo CEDVA

- Dar Al Uloom University

- Centro de Estudios Preuniversitarios de la Universidad Nacional de Ingeniería

- 上智大学

- Aakash International School, Nuna Majara

- San Felipe Neri Catholic School

- Kang Chiao International School - New Taipei City

- Misamis Occidental National High School

- Institución Educativa Escuela Normal Juan Ladrilleros

- Kolehiyo ng Pantukan

- Batanes State College

- Instituto Continental

- Sekolah Menengah Kejuruan Kesehatan Kaltara (Tarakan)

- Colegio de La Inmaculada Concepcion - Cebu