Topic 5 - Constructivist Approaches (Solution-Focused) Theories of Psychotherapy and Counseling Notes PDF

| Title | Topic 5 - Constructivist Approaches (Solution-Focused) Theories of Psychotherapy and Counseling Notes |

|---|---|

| Course | Advanced Counseling Theories-Addiction & Substance Use Disorder Counselors |

| Institution | Grand Canyon University |

| Pages | 8 |

| File Size | 150.6 KB |

| File Type | |

| Total Downloads | 66 |

| Total Views | 123 |

Summary

Full book notes for topic...

Description

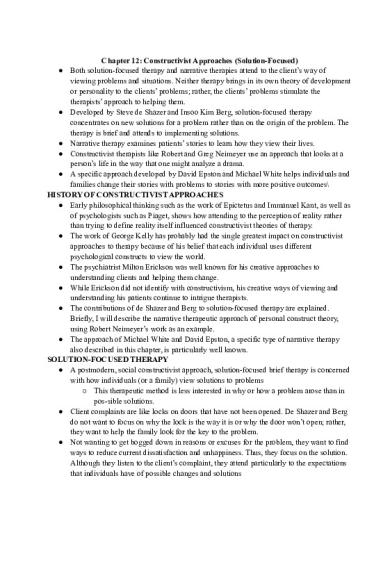

Chapter 12: Constructivist Approaches (Solution-Focused) ● Both solution-focused therapy and narrative therapies attend to the client’s way of viewing problems and situations. Neither therapy brings in its own theory of development or personality to the clients’ problems; rather, the clients’ problems stimulate the therapists’ approach to helping them. ● Developed by Steve de Shazer and Insoo Kim Berg, solution-focused therapy concentrates on new solutions for a problem rather than on the origin of the problem. The therapy is brief and attends to implementing solutions. ● Narrative therapy examines patients’ stories to learn how they view their lives. ● Constructivist therapists like Robert and Greg Neimeyer use an approach that looks at a person’s life in the way that one might analyze a drama. ● A specific approach developed by David Epston and Michael White helps individuals and families change their stories with problems to stories with more positive outcomes\ HISTORY OF CONSTRUCTIVIST APPROACHES ● Early philosophical thinking such as the work of Epictetus and Immanuel Kant, as well as of psychologists such as Piaget, shows how attending to the perception of reality rather than trying to define reality itself influenced constructivist theories of therapy. ● The work of George Kelly has probably had the single greatest impact on constructivist approaches to therapy because of his belief that each individual uses different psychological constructs to view the world. ● The psychiatrist Milton Erickson was well known for his creative approaches to understanding clients and helping them change. ● While Erickson did not identify with constructivism, his creative ways of viewing and understanding his patients continue to intrigue therapists. ● The contributions of de Shazer and Berg to solution-focused therapy are explained. Briefly, I will describe the narrative therapeutic approach of personal construct theory, using Robert Neimeyer’s work as an example. ● The approach of Michael White and David Epston, a specific type of narrative therapy also described in this chapter, is particularly well known. SOLUTION-FOCUSED THERAPY ● A postmodern, social constructivist approach, solution-focused brief therapy is concerned with how individuals (or a family) view solutions to problems ○ This therapeutic method is less interested in why or how a problem arose than in pos-sible solutions. ● Client complaints are like locks on doors that have not been opened. De Shazer and Berg do not want to focus on why the lock is the way it is or why the door won’t open; rather, they want to help the family look for the key to the problem. ● Not wanting to get bogged down in reasons or excuses for the problem, they want to find ways to reduce current dissatisfaction and unhappiness. Thus, they focus on the solution. Although they listen to the client’s complaint, they attend particularly to the expectations that individuals have of possible changes and solutions

Views About Therapeutic Change ● Solution-focused therapists view clients as wanting to change, and therapists do their best to help bring about change. Because solutions are different for each client, it is particularly important to involve clients in the process of developing solutions. ○ By taking one step at a time and making small changes, larger changes can be made. ○ Solution-focused therapy takes advantage of client strengths and gives a positive view of the future and ways to find solutions to a variety of problems ○ Solution-focused therapy is very practical. The therapist examines whether a problem needs changing. If there is a solution to the problem, the therapist identifies the solution the client is using and compliments the client for using it ● Subtly getting clients to stop what they are doing or to do something else can be helpful in bringing about change Assessment ● Unlike many other therapies, solution-focused therapy is not concerned with making diagnostic categorizations; rather, the therapist assesses openness to change ● The therapist is interested in finding out how motivated the client is to change and if the client knows what she wants to change. ● Change starts with smaller problems leading to bigger changes. ● De Shazer (1985) made extensive use of mapping the sequence of behaviors within families, couples, and individuals. ○ Mindmaps, which are diagrams or outlines of the session, are made during or after the session and used for the therapist to focus on organizing the goals and solutions to the problems. ○ Mindmaps may also be used when therapists take a break to get consultation from colleagues or supervisor Goals ● It is important that goals be clear and concrete. ○ Questions make the goals clearer. ○ Important that goals be small so that several small goals can be met rather quickly. ● Often the client is asked to rate progress on the goals on a scale from 0 to 10. ● One technique that relates directly to feedback about progress on goals is “the message.” ○ Messages, written or oral, are explicit and given to the client at the end of the session. ■ Compliments about progress or other aspects of the therapy. ■ Suggestions that will help the clients solve their problems. Techniques of Solution-Focused Therapy ● All of these techniques are often used in the first session of therapy. ● They may be used in subsequent sessions as well. ● In the second and other sessions, therapists are careful to follow up on changes that the

● ●

●

●

●

●

client has made. They look for successes even if they are relatively small. Although narrative therapists may use a variety of other approaches related to understanding the client’s story, all focus on how the client can look differently at her story to bring about a new sense of hope or accomplishment. Forming a collaborative relationship: ○ Therapists listen carefully to what clients want to change. ○ Asking about what has changed between the time that the appointment was made and the first session is a way to both acknowledge the client’s power to change on her own and to focus the session on change. ○ Counselors wish to be empathic with the client. ○ Become more empathic and respectful with clients through active listening, feeling reflections, goal setting, focusing on the present, and asking questions. ○ Labeling the problem is often helpful. Complementing: ○ This is a method that is positive and helps clients feel more encouraged. ■ Often helpful in the first session. ○ Berg and de Jong discuss three types of complimenting: direct, indirect, and selfcompliments. ■ Direct compliments are based on observations of actions that clients have found to be successful. They then bring the client’s success with the action to his attention. ■ Indirect compliments come from asking clients questions that are similar to points of view of family and friends. ■ Self-complementing refers to asking questions in a way that clients need to answer by talking about success or their abilities Pretherapy change: ○ Solution-focused therapists examine change that has taken place even before the client arrives at the therapist’s office. ■ The act of making an appointment is a positive indicator for change. ■ Asking “What have you done since you called for the appointment that has made a difference in your problem?” sets a tone for a focus on solutions and change. ○ In this way, the therapist focuses on the client’s own abilities to bring about change rather than the therapist giving the client solutions. Coping questions: ○ By finding out how clients cope, therapists can build on their coping skills even when clients’ problems seem very difficult. ○ It is better for the therapist to use “When” rather than “If.” ○ The question “How did you do it?” empowers the client by helping him think about resources and methods he used to deal with a difficult situation.

● The miracle question: ○ Developed by de Shazer ○ “Imagine when you go to sleep at night a miracle happens and the problems we’ve been talking about disappear. As you were asleep, you didn’t know that a miracle had happened. When you woke up, what would be the first signs for you that a miracle had happened?” ○ De Jong and Berg suggest that this question be given slowly so that the client can think about it and discuss her preferred future. By answering this question, the client is laying out goals for change. ○ “What else?” In solution-focused therapy, “What else?” is a frequently used phrase, as it helps the client come up with more goals or potential solutions ○ Miracle questions may be about how the client would feel or how the client would think. ● Scaling questions: ○ Scaling questions help clients set goals, measure progress, or establish priorities for taking action ■ On a scale of one to ten, with ten representing the best it can be and zero the worst, where would you say you are today? ■ Would staying where you are on the scale be good enough for now, given all the pressures on you? ■ What do you need to do, or not do, to prevent you from going down the scale? ■ What was happening at the time when you were higher? ● Assessing motivation: ○ Scaling questions are often used to assess the motivation for change. ○ When asking the client to quantify the level of motivation, the counselor is also asking questions that elicit ideas of behaviors that the client will do that are partial solutions to the problem. ● Exception-seeking questions: ○ Questions that ask when the problem did not occur are important. ■ Asking about a time when the client did something that made a difference in the problem is very helpful ○ Therapists often follow exception-seeking questions up with “What else?” questions. ○ Therapists frequently compliment the client for using ingenuity and creativity in developing solutions for the problem. ○ Therapists are careful not to be condescending when doing so. ○ The solutions that therapists have heard then become solutions that can be planned and developed to be used in the next week. ● Formula first session tasks: ○ Solution-focused therapists not only want to emphasize the importance of change,

they also want to show that change is inevitable. ○ The therapist does not ask if something happens, but what happens. There is the expectation that change will happen. ○ In this way the client feels understood before making changes. When the client comes to the second session, the client is asked what did happen and what she observed. ● “The message”: ○ Many solution-focused therapists will stop the session 5–10 minutes early to give the client a written message as feedback about the session ○ This message is somewhat similar to the invariant prescription given by family therapists using methods developed by the Milan associates. ○ The message given at the end of a session of solution-focused therapy is more straightforward than the invariant prescription. ■ The client is given positive feedback. ■ A summary of the client’s achievements follows this. ■ A bridge is then made to relate the client’s change to the goals that have been developed. ■ Then tasks or suggestions are given to the client. These may be ones where the client is asked to notice positive change (an observational task), times when the expanded problem is handled better, or times when something they want to have happen happens. Sometimes clients will be asked to try a different task or to try a pretend task (a behavioral task). NARRATIVE THERAPY ● Narrative therapists attend to their clients’ stories that contain problems. Telling the same story from different points of view or emphasizing different aspects of these stories enables clients to work through problems in their lives Personal Construct Theory ● Just as we learn to analyze novels in English classes by attending to the setting, characters, plot, and themes, so do personal construct therapists analyze client stories. ● Setting: ○ Where and when the story takes place is the setting of a story. ● Characterization: ○ The people (or actors) in the story are called characters. ○ Frequently, the client is the protagonist, or central character. ○ There are also antagonists (the people in conflict with the protagonist), as well as supporting characters. ○ The personality and motive of the characters can be described by the client (narrator) directly or may emerge in the telling of the story. ○ Sometimes clients may tell a story, and at other times, they may act part of it out by being a character or by using a technique such as the gestalt two-chair (or empty-chair) approach

● Plot: ○ Learning what has happened is the role of the plot. ○ As the plot unfolds, we follow the actions of the characters in the setting of the narrative. ○ Sometimes the therapist helps the client put the episodes together in a manner that is coherent to the client. ○ Often clients may tell the story more than once, and different plots or views of the plot develop. ○ Also, with repeated retelling of the story, plots with difficult problems (problemsaturated) may develop new solutions. ● Theme: ○ The reasons things happen in the story are referred to as themes. ○ It is the clients’ understanding of the story, not the therapist’s, that is the focus of the therapist. ○ Sometimes clients may have an emotional understanding, a cognitive understanding, a spiritual understanding, or some combination of these. Therapists may use different techniques to help clients understand the themes of their stories. EPSTON AND WHITE’S NARRATIVE THERAPY ● Listening to their clients’ stories and focusing on the importance of the stories and alternative ways of viewing them characterize the work of Michael White and David Epston ● The key to change in families (or individuals) is the reauthoring or retelling of stories. ● White and Epston take a social constructionist view of the world. They are interested in how their clients perceive events and the world around them. Assessment ● Narrative therapists do not diagnose or try to find why the problem occurred; rather, they listen for how the client’s story develops so that they may develop a new alternative. ● They use maps of the story. They often write down what the client is saying so that they have a map of how the story proceeds. ● Assessment may start with asking about what the client would like to happen in therapy. Then as the client talks about the influence of the problem on the family and the difficulties that result, the therapist records this and follows the discussion. ○ “When did you first notice the problem entered your life?” moves away from blaming the client to externalizing the problem. ○ To facilitate this exploration, the therapist may ask questions such as “How is it that you avoid making mistakes that most people with similar problems usually make?” and “Were there times in the recent past when this problem may have tried to get the better of you, and you didn’t let it?” ● Such questions also point out to clients that the problems are not their lives and do not necessarily dominate their lives.

● Such questions encourage the development of positive unique outcomes Goals ● Epston and White try to help their clients see their lives (stories) in ways that will be positive rather than problem saturated. ● They help their clients shape meaning from the characters and plots in their stories so that they can overcome their problems. ● They believe in the power of words to affect the way individuals see themselves and others. ● They offer hope that new solutions can be achieved. Techniques of Narrative Therapy ● The techniques that narrative therapists use have to do with the telling of the story. ● They may examine the story and look for other ways to tell it differently or to understand it in other ways. ● Externalizing the problem: ○ The problem becomes the opponent ○ This places the problem outside and makes it a separate entity, not a characteristic of the individual. ○ This paves the way for finding different solutions rather than blaming the individual for the problem. ○ The therapist can then deconstruct a problem or story and then reconstruct or reauthor a preferred story. ● Unique outcomes: ○ When narrative therapists listen to a story that is full of problems, they look for exceptions to the stories. ○ Questions reveal exceptions that are seen as sparkling moments or as unique outcomes. ■ These moments may consist of thoughts, feelings, or actions that are different from those found in the problem that family members have. ○ By focusing on these unique outcomes, narrative therapists start to explore the influence the family may have over the problem. This can begin a new story. ● Alternative narratives: ○ Exploration of strengths, special abilities, and aspirations of the family and the person with the problem is the focus of the alternative narrative or story. ○ Therapists comment on the positive aspects of what the identified patient or family is doing and develops them into a new way of viewing the problem. ○ In this way, the narrative therapist helps clients see strengths by telling their stories about themselves in a more powerful and positive way. ● Positive narratives: ○ Narrative therapists not only examine problem-saturated stories, but they also look for stories about what is going well. ○ Sometimes clients are so focused on or stuck in problem-saturated stories that it is

difficult for them to see any positive stories (things that they are doing well). ○ Clients may ignore these positive stories, but therapists may ask for them so that they can point out to the client how she has come up with effective ways to solve some problems. ○ Such positive stories can give clients a sense of empowerment. ● Questions about the future: ○ As change takes place, therapists can assist the client in looking into the future and at potentially positive new stories ○ Questions help therapeutic changes continue beyond the termination of therapy. ● Support for client stories: ○ To emphasize the stories that clients tell and to help the therapeutic effect of reauthoring the stories, narrative therapists use letters, web pages, certificates, leagues, and the involvement of others to help new changes stay with the client ■ Letters written by the therapist summarize the session and externalize the problem. ● Such letters are positive and highlight the client’s strengths. ● They focus on the unique outcomes of exceptions to the problem. ● Direct quotes from the session may be used. ● Also, questions or comments that the therapist thought about after the session can be included. ● Letters are mailed between sessions and at the end of therapy. Clients often report rereading the letters to help them continue to make progress on the problem. ● Letters may also be written to those who know the client well, asking for answers to questions that will provide support for the client. ■ Certificates, usually used with children, help to mark change and foster pride in having made changes. ■ Leagues have been initiated to develop support from others for clients. ■ Support for client stories can also come from parents, siblings, friends, or others. ● From a narrative point of view, the client has a receptive audience to applaud or appreciate her progress.

References Sharf, R.S. (2012). Theories of psychotherapy and counseling: Concepts and cases (5th ed.). Belmont, CA: Cengage Learning....

Similar Free PDFs

Theories in Counseling Chart

- 20 Pages

Theories IN School Counseling

- 12 Pages

Math1081-topic 5-notes

- 38 Pages

Topic 5 Credibility Notes

- 8 Pages

Theories of Personality - Notes

- 16 Pages

History of School Counseling

- 8 Pages

Popular Institutions

- Tinajero National High School - Annex

- Politeknik Caltex Riau

- Yokohama City University

- SGT University

- University of Al-Qadisiyah

- Divine Word College of Vigan

- Techniek College Rotterdam

- Universidade de Santiago

- Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Johor Kampus Pasir Gudang

- Poltekkes Kemenkes Yogyakarta

- Baguio City National High School

- Colegio san marcos

- preparatoria uno

- Centro de Bachillerato Tecnológico Industrial y de Servicios No. 107

- Dalian Maritime University

- Quang Trung Secondary School

- Colegio Tecnológico en Informática

- Corporación Regional de Educación Superior

- Grupo CEDVA

- Dar Al Uloom University

- Centro de Estudios Preuniversitarios de la Universidad Nacional de Ingeniería

- 上智大学

- Aakash International School, Nuna Majara

- San Felipe Neri Catholic School

- Kang Chiao International School - New Taipei City

- Misamis Occidental National High School

- Institución Educativa Escuela Normal Juan Ladrilleros

- Kolehiyo ng Pantukan

- Batanes State College

- Instituto Continental

- Sekolah Menengah Kejuruan Kesehatan Kaltara (Tarakan)

- Colegio de La Inmaculada Concepcion - Cebu