Jessica Davies 1379481 written-assignment PDF

| Title | Jessica Davies 1379481 written-assignment |

|---|---|

| Course | Clinical Project |

| Institution | Auckland University of Technology |

| Pages | 7 |

| File Size | 182.5 KB |

| File Type | |

| Total Downloads | 85 |

| Total Views | 126 |

Summary

Essay discussing cultural competence- Turanga Kaupapa, Partnership and other practice standards. ...

Description

Running head: Cultural Safety in Midwifery Practice Jessica Davies-Shirley, ID:1379481

1

Cultural Safety: Combined Essentialist & Constructivist Perspectives applied to Maori Midwifery Care – Mahia’s birthing requirements Clinical Project: MIDW610 Auckland University of Technology Jessica Davies-Shirley ID: 1379481 W/C: 1626 +/- 10% (EXCL. in-text citations, and diagram)

Running head: Cultural Safety in Midwifery Practice Jessica Davies-Shirley, ID:1379481

2

Introduction Cultural safety is a significant competency when providing unharmful, and appropriate midwifery care (New Zealand College of Midwives [NZCOM], 2015; New Zealand Psychologists Board [NZPB], 2009; New Zealand Midwifery Council [NZMC], 2012). The health status of Maori within Aotearoa has been significantly impacted over a long period of time; dating back to colonisation, which resulted in a widespread loss of cultural practices, beliefs, and Te Reo Maori (NZPB, 2009; NZMC, 2012). The loss of cultural practices, beliefs, and language has had a direct impact on our current healthcare model; Ramsden (2002) discusses that Maori currently have little control over health policy, the delivery of health services, and funding within the state sector, resulting in passive consumption of healthcare services without apparent input into the service, or appropriate health advocacy (NZPB,2009) Several studies inform us that the merit of cultural safety lies in the reduction of harm to an individual, reduction of healthcare inequity, and the promotion of Mana. Throughout this Case Study the essentialist and constructivist perspectives are explored and applied to the birthing requirements of Mahia, a 21-year-old primiparous Maori woman, while the merit of competent cultural safety and underlying midwifery frameworks are explored and applied to Mahia’s care. The Essentialist and Constructivist Perspectives The Turanga Kaupapa framework is based upon an essentialist perspective of cultural safety, while the constructivist perspective is present as a whole after partnership, and cultural competence standards of practice are combined (NZCOM, 2015). The essentialist perspective on culture and cultural safety is dominant within healthcare literature and is based solely upon understanding and respecting the beliefs, values, and traditions of a group, and is viewed as unchanging; however, it is suggested that solely utilizing this perspective can potentially hide the diversity of each individual group/patient (Garneau & Pepin, 2015; Garran & Werkmeister Rozas, 2013; Gray & Thomas, 2006; Williamson & Harrison, 2010). The singular essentialist perspective has been described as an ineffective tool as it does not accommodate for the rapidly changing societal, and socioeconomic factors necessary to formulate completely adequate cultural safety. The essentialist perspective is often taught during the training of healthcare professionals, and has been taught throughout the midwifery curriculum, however the constructivist paradigm is heavily incorporated into training due to the compulsory partnership, and additional cultural competence frameworks that are required by the New Zealand Midwifery Council (Garneau & Pepin, 2015; Auckland University of Technology [AUT], 2016; Garran & Werkmeister Rozas, 2013; Gray & Thomas, 2006; NZMC, 2007). The constructivist perspective recognises culture, and cultural safety as complex, and rapidly evolving (Garneau & Pepin, 2015; Garran & Werkmeister Rozas, 2013; Gray & Thomas, 2006; Williamson & Harrison, 2010). The perspective recognizes that other factors have influence on an individuals’ cultural requirements and inequalities; the relevant factors include historical, political, economic, and social, and they should be acknowledged and understood by the culturally safe healthcare practitioner (Garneau & Pepin, 2015; AUT, 2016; NZMC, 2012; NZMC, 2007). The partnership, and Turanga Kaupapa standards of practice successfully incorporate the constructivist and essentialist perspectives by ensuring that midwives can acknowledge different individual elements that can influence a woman’s cultural perspective; her Whakapapa, Hau Ora, social-political-economic history, and the complex diversity of each woman and her whanau (NZMC, 2012; AUT, 2016; NZMC, 2007). Within midwifery, the constructivist, and essentialist perspectives, and standards of care work in

Running head: Cultural Safety in Midwifery Practice Jessica Davies-Shirley, ID:1379481

3

synchrony to achieve culturally safe, and competent care, moreover, reducing healthcare inequity and inequality for culturally diverse women.

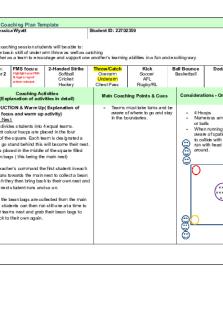

Essentialist Perspective: Beliefs Traditions Finding meaning Values

Constructivist Perspective:

Culturally safe Midwifery care

Individualized Social, economic, historical and cultural factors considered Diversity acknowledged Practitioner reflects upon differences between own culture and power.

*Shape filled by Jessica Davies, informed by Garneau & Pepin (2015); Garran & Werkmeister Rozas (2013); Gray & Thomas (2006); Williamson & Harrison (2010); NZMC (2012); NZPB (2009).

Mahia’s Birthing Requirements When first meeting Mahia at 41+3/40, it was imperative to understand, and recognise Mahia as in individual, and as an expert of her own unique cultural requirements (Pairman & McAraCooper, 2010; Pairman, Pincombe, Thorogood & Tracy, 2015).Turanga Kaupapa and the combined perspectives were utilized while working in partnership with Mahia and her whanau; as well as using a kind greeting and gaining informed consent, Mahia’s Whakapapa, Mana, Hau Ora, and Whanau were acknowledged, and respected from the onset of care (NZCOM, 2015; HDC, 1996; Garneau & Pepin, 2015). It is important to acknowledge the significance of incorporating whanau support into care; studies suggest that whanau inclusion in care can reduce maternal stress and anxiety levels while receiving maternity services (Kopec et. al., 2015). After some discussion, the essentialist perspective was initially taken to achieve culturally safe care; brief enquiry into cultural beliefs and requirements was used as a baseline in establishing individualized care (Garneau & Pepin, 2015). It was then important to understand and respect the cultural differences and beliefs of Mahia and her whanau, and to appreciate the constructivist perspective of Mahia as an individual; every requirement, and decision is affected by external factors- Mahia felt that her historical cultural practices were the most important throughout her childbirth experience (NZMC, 2012; Garneau & Pepin, 2015). Mahia appreciated being asked about her cultural requirements; when a healthcare practitioner inquires and respects the cultural practices of their patients, greater health outcomes

Running head: Cultural Safety in Midwifery Practice Jessica Davies-Shirley, ID:1379481

4

are achieved in terms of patient satisfaction, and reduced harm to the patients’ Hau Ora (NZCOM, 2015; NZMC, 2012; Pairman, Pincombe, Thorogood & Tracy, 2015). Mahia’s cultural requirements during her birthing experience included: Karakia by whanau immediately prior to birth Placenta to be kept by Whanau All tissue and blood products to be kept by whanau Mahia’s cultural requirements were similar to what is traditionally practiced by Maori Wahine and whanau, however it was important to recognise Mahia and her whanau as unique, with individual cultural requirements that are dependent on factors pertaining to both the essentialist and constructivist perspectives (Garneau & Pepin, 2015; Pairman, Pincombe, Thorogood & Tracy, 2015; NZCOM, 2015). Being aware of Mahia’s unique constructivist and essentialist factors provided the practitioner with enough theoretical, and intuitive information to enable the practitioner to provide individualized care, and to practice Partnership, Turanga Kaupapa, and overall cultural safety appropriately (Pairman, Pincombe, Thorogood & Tracy, 2015; Pairman & McAra-Cooper, 2010). To protect Mahia’s Mana, Hau Ora, and cultural requirements, effort was made to ensure that the appropriate respectful, and individualized care was maintained; this meant that the practitioner remained silent to assist in facilitating whanau Karakia, returned the Whenua to the whanau immediately after inspection, and disposable items that had been utilized during the birth e.g. blood stained incontinence sheets were not disposed of by the practitioner, and were instead, given to Mahia’s whanau for safe keeping. Mahia achieved a normal birth, however her postnatal outcome is unknown. Midwifery Frameworks & Legislation Relevant to Mahia’s Care In an effort to reduce and prevent further disparity and inequity of Maori healthcare consumers like Mahia, several regulations and frameworks have been introduced into the healthcare model. The Health and Disability Commission established the code of rights in 1996 for all healthcare consumers; right 1, clause 3 directly addresses the need for cultural safety within healthcare; discussing that Maori culture and beliefs must be respected by healthcare providers (Health and Disability Commission [HDC], 2018; HDC, 1996). Turanga Kaupapa assists midwives to meet the requirements of the code, placing precedence on upholding the Mana, Hau Ora, Manaakitanga, and Whakapapa of a Wahine and her whanau. To reduce healthcare inequity of Maori Wahine and Whanau, and to increase cultural safety within the midwifery profession, Nga Maia o Aotearoa me Te Waipounamu established the Turanga Kaupapa model in conjunction with the New Zealand College of Midwives, and the New Zealand Midwifery Council in 2006 (NZCOM, 2018; NZMC, 2012).Turanga Kaupapa has since become a midwifery framework for practice, alongside partnership, and cultural competence (NZMC, 2012). The Health Practitioners Competence Assurance Act (HPCAA) 2003 became an established regulation in conjunction to the HDC Code of Rights; its’ purpose is to “protect the health and safety of members of the public by providing for mechanisms to ensure that health professionals are competent and fit to practise their profession”; healthcare practitioners are required to demonstrate a competent level of cultural safety at all times, to reduce the risk of harm to consumers (NZMC, 2012; New Zealand Government, 2003). In conjunction with the HPCAA (2003), the New Zealand Midwifery council states in section 118(i) “standards of clinical competence, cultural competence, and ethical conduct are to be observed by practitioners of the profession” (NZMC, 2012; NZMC, 2007; NZMC, 2007). Cultural competence requires a midwife to recognise the impact of their own beliefs and culture on their midwifery practice, and that the midwife must be

Running head: Cultural Safety in Midwifery Practice Jessica Davies-Shirley, ID:1379481

5

able to incorporate, and acknowledge each woman’s cultures into individualized midwifery care (NZCOM [New Zealand College of Midwives], 2015; NZMC, 2012; NZMC, 2007). By acknowledging Mahia as an individual and providing respectful, and culturally safe care accordingly, the standards of the HDC (1996) code of rights, Turanga Kaupapa, HPCAA (2003), NZCOM, and NZMC were met in a simplistic, yet effective way. In 14 separate studies, Beach et. al. (2005) discussed that health professionals whom had been educated on cultural competency, and practiced cultural safety achieved higher patient satisfaction, compliance, and overall positive health outcomes. The overall goal, and merit of all frameworks is to provide respect, and protection of an individuals’ culture, and to provide culturally safe care- respect and dignity is maintained throughout midwifery care through acknowledgement, appreciation, and understanding. Shah (2015) demonstrates that cultural incompetency, including lack of individualized care can cause significant long-term harm, including loss of life in some extreme cases, and can discourage individuals from seeking help in the future; which gives rise to the importance of cultural safety in practice. While poorly practiced cultural safety has significant potential to cause harm to an individual, competent cultural safety has the ability to widely improve healthcare outcomes, and the overall consumer healthcare experience (Pairman, Pincombe, Thorogood & Tracy, 2015). Cultural safety has shown to lead to favourable partnerships between woman and midwife; in-turn, creating a feeling of emotional warmth, protection, reassurance, and lower maternal anxiety levels (NicoloroSantaBarbara, Rosenthal, Auerbach, Kocis, Busso & Lobel, 2017).

Conclusion In conclusion, the merits of applying cultural safety within midwifery practice are widespread; ranging from increasing trust, Mana/respect and reassurance levels shared within the Wahine and midwifery partnership and decreasing cultural inequity and inequality within the healthcare sector. While cultural safety has its’ direct consumer benefits (e.g. reduction in anxiety, and improved patient satisfaction), the main, and overall merit is that cultural safety protects, and promotes the individualistic cultural qualities that each woman possesses and reduces the healthcare inequity of Maori. It is important that healthcare providers are reminded that culture is not static; culture is ever changing, and reflects both, the essentialist and constructivist perspectives. While valuing beliefs, traditions, and other cultural aspects that generate meaning, it is important to complement these essentialist values with the constructivist, as it reflects the individuality, history, and diversity of the Wahine and her Whanau. The midwifery frameworks- Partnership, Turanga Kaupapa, and Cultural competence work together to create a culturally safe healthcare environment for women receiving maternity services. The essentialist and constructivist views were applied to Mahia’s care, alongside Turanga Kaupapa and Partnership; a knowledge of Maori culture, diversity, and inequity within Aotearoa was significant in providing, and informing culturally safe and competent care.

Running head: Cultural Safety in Midwifery Practice Jessica Davies-Shirley, ID:1379481

6

References Auckland University of Technology. (2016). Programme Document. BHsC Midwifery. Recovered from [email protected] Indrani Govindsamy. 09/07/2018. Beach, M. C., Price, E. G., Gary, T. L., Robinson, K. A., Gozu, A., Palacio, A., Smarth, C., Jenckes, M. W., Feuerstein, C., Bass, E. B., Powe, N. R., Cooper, L. A. (2005). Cultural competence: a systematic review of health care provider educational interventions. Medical care, 43(4), p.356-373. Garneau, A. & Pepin, J. (2015) Cultural Competence: A Constructivist Definition. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 26(1) 9–15. DOI: 10.1177/1043659614541294 Garran, A. M., & Werkmeister Rozas, L. (2013). Cultural competence revisited. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work. 22, 97-111. Gray, D. P., & Thomas, D. J. (2006). Critical reflections on culture in nursing. Journal of Cultural Diversity.13(2), p. 76-82. Health and Disability Commissioner (1996). Code of Health and Disability Services Consumers' Rights. Retrieved from: https://www.hdc.org.nz/your-rights/about-the-code/code-of-health-and-disabilityservices-consumers-rights/ Health and Disability Commissioner (2018). Formation of HDC. Retrieved from: https://www.hdc.org.nz/about-us/history/ Kopec, J. A., Ogonowski, J., Rahman, M., & Miazgowski, T. (2015). Patient-reported outcomes in women with gestational diabetes: a longitudinal study. International Society of Behaviour Medicine, 22, pp. 206– 213. doi:10.10007/s12529-014-9428-0 Midwifery Council of New Zealand (2007). Competencies for entry to the Register of Midwives. Retrieved from: www.midwiferycouncil.health.nz/ Midwifery Council of New Zealand (2007). Standards for approval of pre-registration midwifery education programmes and accreditation of tertiary education organisations. New Zealand College of Midwives. (2015). Midwives handbook for practice. Christchurch, New Zealand. New Zealand Government. (2003). Health Practitioners Competence Assurance Act. New Zealand Psychologists Board. (2009). Guidelines for Cultural Safety: The Treaty of Waitangi and Māori Health and Wellbeing in Education and Psychological Practice. Wellington. Retrieved from: http://www.psychologistsboard.org.nz/cms_show_download.php?id=83 Nicoloro-SantaBarbara, J., Rosenthal, J., Auerbach, M., Kocis, C., Busso, C., & Lobel, M. (2017). Patientprovider communication, maternal anxiety, and self-care in pregnancy. Social Science & Medicine. Retrieved from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.08.011

Running head: Cultural Safety in Midwifery Practice Jessica Davies-Shirley, ID:1379481 Nursing Council of New Zealand (2012). Guidelines for Cultural Safety, the Treaty of Waitangi and Maori Health in Nursing Education and Practice. Retrieved from: www.nursingcouncil.org.nz/download/97/cultural-safety11.pd Pairman, S & McAra-Couper, J. (2010).Theoretical frameworks for midwifery practice In Pairman, S., Tracy, S, Thorogood, C & Pincombe, J. Midwifery: preparation for practice,2nd edition. Sydney: Elsevier. Pairman, S., Pincombe, J., Thorogood, C., & Tracy, S. (2015). Midwifery Preparation for Practice (3rd ed). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. Ramsden, I. (2002). Cultural safety and nursing education in Aotearoa and Te Waipounamu. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Massey University, Wellington Retrieved from: http://publichealth.massey.ac.nz/kawawhakaruruhau/thesis.htm Shah. (2015). Case Report: Culturally Incompetent Care: Endangers Life. Journal of Clinical Research & Bioethics. doi: 10.4172/2155-9627.1000237 Williamson, M., & Harrison, L. (2010). Providing culturally appropriate care: A literature review. www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2003/0048/latest/DLM203312.html

7...

Similar Free PDFs

Portafolio ITB-convertido Jessica

- 12 Pages

Jessica WU - OB scenario

- 1 Pages

Reflexión Jessica Gómez 3PDF

- 1 Pages

Peer coaching plan jessica

- 5 Pages

Jessica Method (1)

- 82 Pages

OB SR Jennifer Jessica Jenny

- 15 Pages

Chapter 7 hw - jessica tietjen

- 2 Pages

Jessica Java Sample LR Trail

- 3 Pages

Popular Institutions

- Tinajero National High School - Annex

- Politeknik Caltex Riau

- Yokohama City University

- SGT University

- University of Al-Qadisiyah

- Divine Word College of Vigan

- Techniek College Rotterdam

- Universidade de Santiago

- Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Johor Kampus Pasir Gudang

- Poltekkes Kemenkes Yogyakarta

- Baguio City National High School

- Colegio san marcos

- preparatoria uno

- Centro de Bachillerato Tecnológico Industrial y de Servicios No. 107

- Dalian Maritime University

- Quang Trung Secondary School

- Colegio Tecnológico en Informática

- Corporación Regional de Educación Superior

- Grupo CEDVA

- Dar Al Uloom University

- Centro de Estudios Preuniversitarios de la Universidad Nacional de Ingeniería

- 上智大学

- Aakash International School, Nuna Majara

- San Felipe Neri Catholic School

- Kang Chiao International School - New Taipei City

- Misamis Occidental National High School

- Institución Educativa Escuela Normal Juan Ladrilleros

- Kolehiyo ng Pantukan

- Batanes State College

- Instituto Continental

- Sekolah Menengah Kejuruan Kesehatan Kaltara (Tarakan)

- Colegio de La Inmaculada Concepcion - Cebu