Tortlaw lecturenotes lectures 1to16 2019 2020 PDF

| Title | Tortlaw lecturenotes lectures 1to16 2019 2020 |

|---|---|

| Author | Sotiris Delizois |

| Course | Tort Law |

| Institution | Manchester Metropolitan University |

| Pages | 22 |

| File Size | 548 KB |

| File Type | |

| Total Downloads | 56 |

| Total Views | 201 |

Summary

Warning: TT: undefined function: 32 Warning: TT: undefined function: 32Lecture notes for “Tort Law” course(academic year 2 019 -2020)OmissionsMisfeasance/Nonfeasance Distinction: - Misfeasance: Positive act which causes harm - Nonfeasance: A mere failure to prevent harm from arising → No liability →...

Description

Lecture notes for “Tort Law” course (academic year 2019-2020) Omissions Misfeasance/Nonfeasance Distinction: • Misfeasance: Positive act which causes harm Nonfeasance: A mere failure to prevent harm from arising → No liability → In the absence of a “special relationship”, there is no duty to go to the rescue of another (Yuen Kun Yeu) → Commentary: Lord Goff stated that the refusal to impose liability for mere omissions might one day need to be reconsidered, in the light of the “affirmative duties of good neighbourliness” imposed in other countries. → Because there is no duty to rescue, in cases where a rescuer chooses to intervene, he or she cannot be liable in negligence UNLESS it can be said that the intervention has made the claimant’s position worse than if it had not taken place (Horsley v MacLaren) • Stovin v Wise - Lord Hoffman: “Liability to pay compensation for loss caused by negligent conduct as a deterrent against increasing the cost of the activity to the community and reduces externalities.” No duty to rescue •

•

•

•

Capital & Counties Plc v Hampshire County Council - Stuart-Smith LJ: “A fire brigade does not enter into a sufficiently proximate relationship with the owner or occupier of premises to come under a duty of care merely by attending at the fire ground and fighting the fire” → No duty is owed for the fire service to take care to attend a fire → Once at the fire, the service has no duty to fight the fire with care - Damage to property does not make the fire service liable - Liability is however allowed if the fire service make the situation worse, as they did by turning off the sprinkler system in Capital & Counties OLL v Secretary of State for Transport - Coastguard does not owe a duty of care in respect of rescue operations unless their activity led to greater injury than would have occurred if they had not been involved. - Not liable as they did not make the situation any worse Alexandrou v Oxford - In the absence of a direct contractual relationship with the Chief Constable, no duty of care was owed

But contrast: • Kent v Griffiths - The judge found that the ambulance could and should have arrived some 14 minutes earlier and that, if it had done so, there was a high probability that the respiratory arrest would have been averted → The ambulance service had breached its duty of care → Allowed her claim for damages - Lord Woolf: “There is no reason why there should not be liability if the arrival of the ambulance was delayed for no good reason. The acceptance of the call in this case established the duty of care.” Existing categories of exception to the no-duty-for-omissions rule: • • •

the defendant’s creation of a source of danger e.g. Haynes v Harwood [1935] 1 KB 146 the defendant’s undertaking of responsibility for the claimant’s welfare e.g. Watson v BBBC [2001] 2 WLR 1256, Kent v Griffiths [2000] 2 All ER 474 the defendant’s occupation of an office or position of responsibility e.g. parents/children (Hahn v Conley (1971) 126 CLR 276 (Australia), Surtees v Kingston-Upon-Thames BC [1991] 2 FLR 559, Perry v Harris [2008] EWCA Civ 907), teachers/pupils (Carmarthenshire County Council v Lewis [1955] AC 549), doctors/patients (Barnett v Chelsea and Kensington [1969] 1 QB 428), and property owners (Goldman v Hargrave [1967] 1 AC 645)

The position of rescuers as victims (claimants) •

Danger invites rescue: Haynes v Harwood [1935] 1 KB 146 Baker v TE Hopkins [1959] 1 WLR 966 Videan v British Transport Commission [1963] 2 QB 650

Liability of 3rd Parties -

Failure to control a 3rd party Failure to prevent a dangerous situation from being sparked off by a 3rd party The defendant provided the 3rd arty with the opportunity or the means to injure the claimant In some circumstances, the intervention of a 3rd party breaks the chain of causation → falls outside the defendant’s liability Home Office v Dorset Yacht Co - This case imposed a duty of care on the defendant to prevent damage being caused by the actions of others → Had a relationship of control over the 3rd parties - There were special relations between the Home Office and the Borstal boys, so that the Home Office could be liable for the guards’ failure to prevent the boys from causing

-

-

damage. → + High degree of foreseeability of the boys escaping and causing the damage as it was the very kind of thing the boys were likely to do. - Lord Reid relied upon considerations of foreseeability or probability as the key to determining whether the causal chain could be traced through the deliberate conduct of the boys. It was the degree of foreseeability or probability present on the facts that served to distinguish those cases where liability should be imposed from those where it should not. - Commentary: The Dorset Yacht case goes beyond Carmarthenshire by recognising a liability for negligent failure to prevent intentional misconduct by a minor for whom the defendant has assumed responsibility, even though the minor is old enough to be held responsible for his actions himself. Palmer v Tees Area Health Authority [1999] - Claim failed → Inadequate proximity between the defendant and the victim - Special requirement needed for the proximity element → The defendant must have had a warning that the victim was at risk of the particular patient → The victim was not more at risk than anybody in the society, hence the claim failed - Duty of this nature will not arise unless proximity shown in 2 relationships: Defendant and Perpetrator; Perpetrator and Victim Clunis v Camden and Islington Health Authority [1998] Newton v Edgerley - Duty on part of parents to prevent their children from harming others will only arise where the parents themselves have somehow actively contributed to the risk of harm

Public Bodies Arguments: ➢ The threat of liability may lead to the local authority adopting overly cautious practices at the public expense ➢ It will undermine or distort the framework of public protection provided by statute ➢ Making local authority to pay compensation is contrary to the general public interest → Forces the authority to divert scarce financial resources away from general public welfare, reallocating them to a small number of litigants ➢ Where Parliament did not intend to create a right to compensation, there can be no claim under the tort of breach of statutory duty (Stovin) -

Stovin v Wise - The local authority had a statutory power to improve the junction, but not a duty to do so → Omission to improve the junction could not be seen as having occurred in the context of any positive obligation to protect the plaintiff from harm

-

-

-

-

-

- “If the policy of the Act is not to create a statutory liability to pay compensation, the same policy should ordinarily exclude the existence of a common law duty of care” Gorringe v Calderdale Metropolitan BC - No duty of care since the statutory duty to “maintain the highway” did not give rise to a duty of care or private enforcement - “Intense focus on the particular facts and on the particular statutory background, seen in the context of the contours of our social welfare state, is necessary” - To infer a private duty of care from a statutory duty the public authority must have ‘assumed responsibility’ for the subject in question and there must be universal reliance. X (a minor) & Others v Bedfordshire County Council & Others - Lord Brown-Wilkinson: “If the decisions complained of fall within the ambit of such statutory discretion, they cannot be actionable in common law” - Caparo Test: Five specific policy factors making it unfair, unjust and unreasonable to impose a duty of care in those instances: (i) a common law duty of care would cut across the whole statutory system set up for the protection of children at risk. (ii) the task of the local authority in dealing with such children is ‘extraordinarily difficult’. (iii) the spectre of liability would perhaps cause local authorities to adopt a more cautious and defensive approach to their duties. (iv) the uneasy relationship between the public authority employee and the child’s parents would become a breeding ground for hopeless litigation. (v) there were alternative remedies available in the form of the statutory complaints procedures or an investigation by the local government ombudsman. Jain v Trent Strategic Authority Will the imposition of a common law duty of care give rise to a conflict with the defendant’s statutory obligations? - House of Lords: “Where action was taken by a state authority under statutory powers designed for the benefit or protection of a particular class of persons, a tortious duty of care would not be held to be owed by the state authority to others whose interests might be adversely affected by an exercise of the statutory power. The imposition of a duty of care would or might inhibit the exercise of the statutory powers and be potentially adverse to the interests of the class of persons the powers had been designed to benefit or protect, thereby putting at risk the achievement of their statutory purpose.” Hill v Chief Constable of West Yorkshire Police - Lord Keith: “If potential liability were to be imposed, the result would be a significant diversion of police manpower and attention from their most important function, that of the suppression of crime” Osman v Ferguson - Following Hill, It would be against public policy to impose such a duty as it would not

promote the observance of a higher standard of care by the police and would result in the significant diversion of police resources from the investigation and suppression of crime.

-

Brooks v Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis Smith v Chief Constable of Sussex Police JD v East Berkshire Community Health Trust

-

Summary of the current position in Negligence: i. Act/omission distinction very important re PA defendants, in same way as with ordinary private defendants. ii. Re omissions claims, same no duty rule applies by default. Mere fact that there is a statutory duty or power to do something does not mean that there is a common law duty in negligence: Stovin v Wise [1996] and Gorringe v Calderdale [2004. iii. To establish exceptional duty of affirmative action, still have to reason by analogy with existing categories: special relationships, assumption of responsibility, creation of situation of danger. But additional hurdle comes in after that in form of policy considerations (most commonly defensive practice, floodgates, conflict of interests). iv. Even in cases of misfeasance, duty may still be negated by policy considerations – Jain v Strategic Health [2009] v. Some PAs treated differently – child protection workers (policy-based immunity partially removed) and the police (policy-based immunity largely intact).

Psychiatric Illness The law would only entertain such claims in cases where psychiatric illness resulted from the “sudden shock” of witnessing or participating in a specific single event. Types of Claimant: 1) WITNESS: Claimants who suffer psychiatric illness as a result of witnessing the death, injury or imperilment of another person with whom they have a close relationship of love and affection (Secondary Victims) → The claimant must establish that psychiatric illness was reasonably foreseeable → A person of ordinary fortitude might reasonably have suffered psychiatric illness in the circumstances 2) PARTICIPANTS: Claimants who suffer psychiatric illness as a result of having been physically injured by the defendant’s negligence

3) PARTICIPANTS: Claimants who are put in physical danger, but who in fact suffer only psychiatric illness (Primary victims) → Claimant must establish that he or she has been placed in immediate physical danger by the defendant’s negligence or at least has been put in reasonable fear for his or her physical safety •

•

•

•

McLoughlin v O’Brian The HoL extended the law to cover a situation where the plaintiff had not seen or heard the accident itself, but had come upon its “immediate aftermath” → As they remained in more or less the same condition they had been in immediately after the accident, she had therefore witnessed scenes which went to “make up the accident as an entire event” Lord Wilberforce identified 3 factors that would need to be considered in every case →The class of persons whose claims should be recognised (The possible range is between the closest of family ties and the ordinary bystander) → The proximity of such persons to the accident (This had to be close in both time and space) → The means by which the psychiatric illness was caused Alcock v Chief Constable of South Yorkshire - A primary victim was one who was present at the event as a participant, and would thus be owed a duty-of-care by D, subject to harm caused being foreseeable, of course - A secondary victim, by contrast, would only succeed if they fell within certain criteria. Such persons must establish: → A close tie of love and affection to a primary victim → Appreciation of the event with their own unaided senses → Proximity to the event or its immediate aftermath (Must normally witness the accident as it actually occurs, or must come upon its immediate aftermath within a very short space of time) → The psychiatric harm must be caused by a sufficiently shocking event. Page v Smith - Primary Victim: The person who is physically harmed or imperilled by the defendant’s negligence - (Primary Victim) Provided personal injury was foreseeable, whether physical or mental, there was no need to establish that the resulting injury is foreseeable - Secondary Victim: “Foreseeability of injury by shock is not enough. The law also requires a degree of proximity…Not only proximity to the event in time and space, but also proximity of relationship between the primary victim and the secondary victim…The secondary victim will only recover damages for nervous shock if the defendant should have foreseen injury by shock to a person of normal fortitude” Lord Lloyd White v Chief Constable of South Yorkshire Lord Steyn – current law on pure psychiatric illness is a patchwork, two solutions:

1) Abolish recovery in tort for pure P-illness – contrary to precedent / highly controversial 2) Abolish all special limiting rules applying to pure P-illness – precedent rules this out + policy reasons for keeping them Only prudent course – treat pragmatic categories (per Alcock, Page) as settled for time being and leaving expansion / development to Parliament Lord Hoffmann – points to trend towards cautious pragmatism in favour of comprehensive system of corrective justice ➔ Stuck with the control mechanism as given in Alcock; conditions limiting liability Plaintiff draws two distinctions between their position and that of a bystander (1) their relation to Constable is analogous to employment owing DoC not to expose him to unnecessary risk (some inherent in being PC) (2) P’s did more than watch – they were ‘rescuers’ qualifying as primary V’s 1) No reasons why employee should suffer injuries which reasonable care could prevent – why should psychiatric illness be treated differently? a. Assumes what it needs to prove – employment only shows that DoC exists, not in which circumstances liability for particular injury arises i. This must be settled by looking at general law of injury in Q (P-illness) b. Can employment status be a reason to give damage for P-illness when if not for that status he would be 2nd V and fail Alcock mechanisms? i. Illustrates danger of incremental expansion – although step from physical to psychiatric seems logical it gives PC’s damages as opposed to ambulance men / first aiders simply because accident caused by other PC’s negligence 2) Although rescuer treated as primary V there is no authority for such findings re Pillness a. No reason why normal treatment of rescuers should lead to conclusion that for P-illness they should get special treatment when not in range of physical injury and only reason for P-illness was witnessing accident Two reasons why law should not be extended on point (2) and allow damages for rescuers P-illness when not coming into range of foreseeable physical injury 1) Definition problems (not v important) – concept of rescuer is easy if confined to someone putting himself in danger of physical injury but if extended to incl person offering assistance the line is blurred 2) Results are unacceptable – offend notions of distributive justice; favouring the less deserving over the more deserving a. Wrong that PC’s should have right to compensation for P-illness while the bereaved relatives were offered none Lord Griffith (dissenting on rescue point)

➔ V artificial to say rescuer can only recover if in physical danger; what rescuer contemplates this beforehand? Probably never gave it thought ➔ Bereavement / grief – part of common condition of mankind which all must endure which rescuing is not o This is different from P-illness

Economic Loss Pure Economic Loss: Loss that is purely financial, in the sense that it does not result from damage to the claimant’s property or injury to the claimant’s person → No duty is owed when the harm in question is purely economic in nature Consequential Economic Loss: Financial loss that is consequential upon damage to the claimant’s person or property (e.g losses suffered by a a claimant who has been seriously injured and must give up work) → Economic loss will be consequential as long as you can link it to an initial kind of personal injury/property damage flowing from the relevant faulty conduct → CEL is ordinarily recoverable •

Spartan Steel v Martin - Damages suffered: 1. Physical damage to property 2. Consequential Economic Loss: Loss of profit on that melt 3. Pure Economic Loss: Loss of profit on the four melts that would have been processed had the electricity not been cut off → Not recoverable because it was purely about loss of profit that couldn’t be attached to damage to any other property 4. CoA allowed the plaintiffs to recover for PD and CEL but not PEL - The defendants owed the plaintiffs a duty not to damage their property and therefore had to pay for the damaged metal and the loss of profit resulting directly from that damage. However, they did not owe a duty of care in respect of the further lost profits because these did not result from the fact that the plaintiff’s property had been damaged → The key is to determine whether or not the claimants already had acquired proprietary interest in the relevant material before the damage occurred → If instead the faulty conduct of D had actually caused damage to part of the factory and as a result of that, they were unable to do anything for a certain period of time → Property damage presence → Loss of profit associated with not being able to do anything would be consequential to property damage and thus recoverable → In Spartan Steel, the loss of profit associated with being unable to work did not relate to any damage to the factory itself, thus not recoverable

•

Murphy v Brentwood District Council → Properties that are already defective when you acquired them, the cost of repairing/replacing is pure economic loss → Not recoverable Lord Keith ➢ Damage characterised by property damage by Lord Wilberforce in Anns was actually economic loss. o With product liability, it is the latency of the defect which causes the injury ▪ Once this becomes apparent • Then it no longer poses such a danger • All you then have to do is either dispose of the chattel or correct it o In both cases, the loss is purely economic. ➢ Since this is the damage, what would happen if we imposed a duty on the council? o Would need a duty on the builders o And therefore any manufacturer ▪ Would be a rather wide field of claims ▪ Cos then you’d have to ask whether if a dangerous defect was discovered before it was dangerous, you’d be entitled to sue for the rectification of it • And then there’s the danger of allowing claims for defects that don’t make property da...

Similar Free PDFs

Lectures IMM 2019-2020

- 26 Pages

Forensicpsych lecturenotes

- 50 Pages

ECE240 pp1-14 - lecturenotes

- 14 Pages

Public Law BORA Lectures 2019

- 15 Pages

ICJ Cases 2019-2020

- 7 Pages

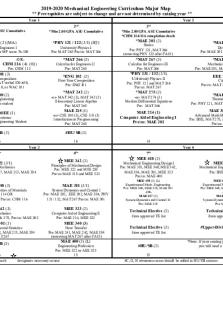

2019-2020 Mechanical Engineering

- 2 Pages

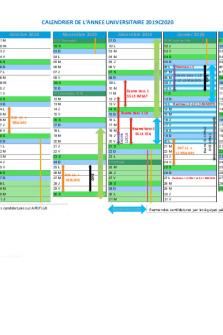

Calendrier 2019-2020 Licence

- 3 Pages

Mock exam 2019-2020

- 8 Pages

KALDIK 2019-2020 JATENG

- 52 Pages

Cronología relativa 2019-2020

- 6 Pages

Samenvatting KST 2019-2020

- 17 Pages

Popular Institutions

- Tinajero National High School - Annex

- Politeknik Caltex Riau

- Yokohama City University

- SGT University

- University of Al-Qadisiyah

- Divine Word College of Vigan

- Techniek College Rotterdam

- Universidade de Santiago

- Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Johor Kampus Pasir Gudang

- Poltekkes Kemenkes Yogyakarta

- Baguio City National High School

- Colegio san marcos

- preparatoria uno

- Centro de Bachillerato Tecnológico Industrial y de Servicios No. 107

- Dalian Maritime University

- Quang Trung Secondary School

- Colegio Tecnológico en Informática

- Corporación Regional de Educación Superior

- Grupo CEDVA

- Dar Al Uloom University

- Centro de Estudios Preuniversitarios de la Universidad Nacional de Ingeniería

- 上智大学

- Aakash International School, Nuna Majara

- San Felipe Neri Catholic School

- Kang Chiao International School - New Taipei City

- Misamis Occidental National High School

- Institución Educativa Escuela Normal Juan Ladrilleros

- Kolehiyo ng Pantukan

- Batanes State College

- Instituto Continental

- Sekolah Menengah Kejuruan Kesehatan Kaltara (Tarakan)

- Colegio de La Inmaculada Concepcion - Cebu