Critical Legal Thinking Study Guide PDF

| Title | Critical Legal Thinking Study Guide |

|---|---|

| Course | Critical Legal Thinking |

| Institution | The University of Edinburgh |

| Pages | 7 |

| File Size | 134.2 KB |

| File Type | |

| Total Downloads | 116 |

| Total Views | 165 |

Summary

This is a study guide for the Critical Legal Thinking Exam. It outlines topics from throughout the course and provides examples to aid understanding. ...

Description

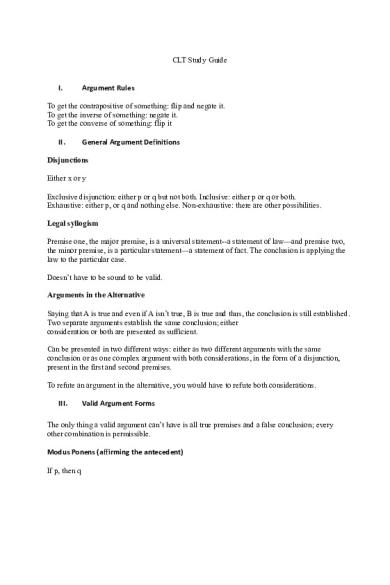

CLT Study Guide

I.

Argument Rules

To get the contrapositive of something: flip and negate it. To get the inverse of something: negate it. To get the converse of something: flip it II.

General Argument Definitions

Disjunctions Either x or y Exclusive disjunction: either p or q but not both. Inclusive: either p or q or both. Exhaustive: either p, or q and nothing else. Non-exhaustive: there are other possibilities. Legal syllogism Premise one, the major premise, is a universal statement--a statement of law—and premise two, the minor premise, is a particular statement—a statement of fact. The conclusion is applying the law to the particular case. Doesn’t have to be sound to be valid. Arguments in the Alternative Saying that A is true and even if A isn’t true, B is true and thus, the conclusion is still established. Two separate arguments establish the same conclusion; either consideration or both are presented as sufficient. Can be presented in two different ways: either as two different arguments with the same conclusion or as one complex argument with both considerations, in the form of a disjunction, present in the first and second premises. To refute an argument in the alternative, you would have to refute both considerations. III.

Valid Argument Forms

The only thing a valid argument can’t have is all true premises and a false conclusion; every other combination is permissible. Modus Ponens (affirming the antecedent) If p, then q

p Therefore (from (1) and (2)), Q *Same as (Contrapositive): If it is not the case that q, then it is not the case that p *If p, then q IS NOT THE SAME as if not p, then not q (inverse) bc the consequent could be right even if the antecedent is false; it could be right for other reasons* *If p, then q IS NOT THE SAME as if q, then p (converse)* Universal modus ponens: For every x: if x is a reasonable person then x would have foreseen that he would hurt someone if he struck a golf ball in their direction. Phil is a reasonable person. Therefore, Phil would have foreseen that he would hurt someone if he struck a golf ball in their direction. Modus Tollens (denying the consequent) If p, then q Not q Therefore (from (1) and (2)), Not p Universal modus tollens: For every x: if x is a reasonable person then x would have foreseen that he would hurt someone if he struck a golf ball in their direction. It is not the case that Phil would have foreseen that he would hurt someone if he struck a golf ball in their direction. Therefore, It is not the case that Phil is a reasonable person. Hypothetical Syllogism If p, then q If q, then r Therefore (from (1) and (2)) If p, then r Disjunctive Syllogism p or q Not p Therefore (from (1) and (2)) Q

*Someone who asserts a disjunctive syllogism is asserting that the disjunction is exhaustive. IV.

Non-deductive arguments

Because we know this, this is probably true. Don’t purport to be valid like deductive arguments. Inductive Specific observation general conclusion Ex: Mitzi is a Weimaraner and Mitzi is grey. Molly is a Weimaraner and Molly is grey. Etc. Therefore, probably, all Weimaraners are grey. To make an inductive argument stronger: increase sample size. Abductive Incomplete observation best explanation Ex: Nick came into class soaking wet. Therefore, probably, it is raining outside. In Law When a court has to decide a case on which there is no directly applicable authority, it will look at a set of previously decided cases, or to a string of legislated provisions, and try to “extract” from them a unifying principle of general application. The process of reasoning from the past cases to the legal principle can be described as something like an inference to the best legal explanation – an “abduction” or “induction” of legal principles from past authoritative judicial decisions. Top-down approach: Premise The principle that best explains cases C1 to Cn is the principle that provides the best common explanation of C1 to C5 Premise The principle that provides the best common explanation of C1 to Cn is principle P Conclusion The principle that best explains C1 to Cn is principle P Bottom-up approach: Premise The principle that best explains C1 is principle P Premise The principle that best explains C2 is principle P ... Premise The principle that best explains Cn is principle P Conclusion The principle that best explains C1 to Cn is principle P

V.

Legal Positions

Correlatives: right and duty, no-right and liberty-not, Contradictories: liberty-not and duty A right in the strict sense involves someone else’s actions; I have a right that you do or not do something. A liberty involves the liberty-holder’s own actions, not someone else’s; I have a liberty to do or not do something; that doesn’t involve a duty on anyone else to allow me to exercise this liberty. I have, towards John, a duty to pay him 10 dollars John has a right, against me, to be paid 10 dollars OR a negative action: I have, towards John, a duty not to hit him below the belt John has a right, against me, not to be hit below the belt. Duty and right are correlative positions. It is not the case that I have, towards John, a duty to pay him 10 dollars I have, towards John, a liberty not to pay him 10 dollars. Duty and liberty-not are contradictory positions (which is why we added “it is not the case that” on the left side) I have, towards John, a liberty not to pay him 10 dollars John has, against me, a no-right that I pay him 10 dollars. Liberty-not and no-right are correlative positions. VI.

Fallacies

Formal fallacies have to do with the form of an argument, so they affect validity. Denying the antecedent If p, then q Not p Therefore, Not q Universal: For every x: if x is a reasonable person then x would have foreseen that he would hurt someone if he struck a golf ball in their direction. It is not the case that Phil is a reasonable person. Therefore, It is not the case that Phil would have foreseen that he would hurt someone if he struck a golf ball in their direction. Affirming the consequent

If p, then q q Therefore, P Universal: For every x: if x is a reasonable person then x would have foreseen that he would hurt someone if he struck a golf ball in their direction. Phil would have foreseen that he would hurt someone if he struck a golf ball in their direction. Therefore, Phil is a reasonable person. Fallacy of Equivocation To use the same term in an argument but in different senses, glossing over which meaning is intended at a particular time. Affirming the Disjunct Concluding that one disjunct of a disjunction must be false because the other disjunct is true when the disjunctive could be inclusive. You could attack an argument affirming the disjunct by saying that the disjunct is not exclusive. Fallacy Fallacy To conclude from the fact that a certain argument is fallacious that its conclusion must be false. Ex: The argument is fallacious Therefore, The conclusion must be false. Just because the argument is fallacious, that does not mean that the conclusion of the argument is false, it just means that the conclusion has not been established by its premises. Illicit conversion Illicit inversion Converting the conditional Inverting the conditional Informal fallacies have to do with the content of an argument; they do not affect validity. Begging the Question

Assuming what you must prove. Also known as a circular argument or petitio principii. P and Q express the same idea. Ex: I have a duty not to hit John below the belt = John has a right against me not to be hit below the belt. This is saying the same thing. When you have correlative positions in the premise and the conclusion, the argument is circular. Straw Man Attacking an argument that is not being made; refuting an irrelevant part of what the other person said. Falls under fallacy of irrelevant conclusion. False Dichotomy Acting like the two possibilities in a disjunction are exhaustive when there could be other possibilities outside of those two. You could attack a disjunctive syllogism by saying that the disjunction (that it is either one or the other) is false bc there are other options. Ex: Every human is either a man or women. There are trans people. Appeal to Authority (argumentum ad verecundiam) Seeking to establish a conclusion by appealing to the fact that someone who is regarded or treated as an authority said so or agrees with you – suggesting that the other party should refrain from questioning their authority because it would be disrespectful.

VII.

Reasons

Pro Tanto A reason that counts in favor of or against something else but does not conclusively decide it. Can be outweighed by countervailing considerations. Ex: Theoretical reasons and judgements from analogous cases A pro tanto reason that is not outweighed by countervailing considerations is a conclusive reason. (1) If p (pro-tanto reason) and there are no countervailing considerations, then q (2) p (3) There are no countervailing considerations Therefore (from (1) and (2) and (3)),

(4) q P on its own is not being presented as individually sufficient for q. P together with the fact that there are no countervailing considerations are being presented as cumulatively (or jointly) sufficient for q. Practical Authority Gives us content-independent reasons to act (practical reason). The say-so of a practical authority gives us a reason to do something and we CANNOT rely on own well-informed view about whether what they say is actually true. It excludes other applicable substantive reasons from weighing in the balance. Ex: Statutes, regulations, by-laws, precedent, etc. Theoretical Authority Gives us content-independent reasons to believe (theoretical reason). The say-so of a theoretical authority gives us a reason to believe what they say but we can still rely on our own well-informed view about whether what they say is actually true. Ex: Obiter dicta, writings of legal scholars, reference works (e.g. dictionaries), decisions of foreign courts, etc. Arguments by Analogy When authority runs out. Gives us a reason to decide a case a particular way because a similar case was decided in that way. However, it is a pro-tanto reason and be outweighed by countervailing considerations....

Similar Free PDFs

Critical thinking

- 14 Pages

Critical Thinking Assignment3-3

- 2 Pages

Critical thinking chapter 4

- 2 Pages

Critical Thinking Debate

- 5 Pages

Critical Thinking Assignment13-3

- 2 Pages

Critical Thinking Assignment4-1

- 2 Pages

8611 critical thinking

- 7 Pages

Mod 5 Critical Thinking

- 2 Pages

Critical Thinking Skills

- 6 Pages

C3 - Critical Thinking Skills

- 2 Pages

Critical Thinking Assignment3-5

- 1 Pages

Popular Institutions

- Tinajero National High School - Annex

- Politeknik Caltex Riau

- Yokohama City University

- SGT University

- University of Al-Qadisiyah

- Divine Word College of Vigan

- Techniek College Rotterdam

- Universidade de Santiago

- Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Johor Kampus Pasir Gudang

- Poltekkes Kemenkes Yogyakarta

- Baguio City National High School

- Colegio san marcos

- preparatoria uno

- Centro de Bachillerato Tecnológico Industrial y de Servicios No. 107

- Dalian Maritime University

- Quang Trung Secondary School

- Colegio Tecnológico en Informática

- Corporación Regional de Educación Superior

- Grupo CEDVA

- Dar Al Uloom University

- Centro de Estudios Preuniversitarios de la Universidad Nacional de Ingeniería

- 上智大学

- Aakash International School, Nuna Majara

- San Felipe Neri Catholic School

- Kang Chiao International School - New Taipei City

- Misamis Occidental National High School

- Institución Educativa Escuela Normal Juan Ladrilleros

- Kolehiyo ng Pantukan

- Batanes State College

- Instituto Continental

- Sekolah Menengah Kejuruan Kesehatan Kaltara (Tarakan)

- Colegio de La Inmaculada Concepcion - Cebu