Diosdado Macapagal - This is helpful PDF

| Title | Diosdado Macapagal - This is helpful |

|---|---|

| Author | Elle Gonzales |

| Course | History |

| Institution | Divine Word College of Calapan |

| Pages | 24 |

| File Size | 1 MB |

| File Type | |

| Total Downloads | 99 |

| Total Views | 174 |

Summary

This is helpful...

Description

Diosdado Macapagal From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to navigationJump to search This article is about the former president of the Philippines. For his grandson and former member of Congress, see Diosdado Macapagal Arroyo. In this Philippine name, the middle name or maternal family name is Pangan and the surname or paternal family name is Macapagal, Sr.. Diosdado P. Macapagal Sr.

GCrM OMRI

Diosdado Macapagal in 1962 9th President of the Philippines

In office December 30, 1961 – December 30, 1965

Vice President

Emmanuel Pelaez

Preceded by

Carlos P. Garcia

Succeeded by

Ferdinand Marcos

2nd President of the 1971 Philippine Constitutional Convention

In office June 14, 1971 – January 17, 1973

President

Ferdinand Marcos

Preceded by

Carlos P. Garcia

Succeeded by

Position abolished 5th Vice President of the Philippines

In office December 30, 1957 – December 30, 1961

President

Carlos P. Garcia

Preceded by

Carlos P. Garcia

Succeeded by

Emmanuel Pelaez

Member of the Philippine House of Representatives from Pampanga's 1st District

In office December 30, 1949 – December 30, 1957

Preceded by

Amado Yuzon

Succeeded by

Francisco Nepomuceno

Personal details

Born

Diosdado Pangan Macapagal

September 28, 1910 Lubao, Pampanga, Philippine Islands

Died

April 21, 1997 (aged 86) Makat, Metro Manila, Philippines

Resting place

Libingan ng mga Bayani, Metro Manila, Philippines 14°31′11″N 121°2′39″E

Nationality

Filipino

Political party

Liberal Party

Spouse(s)

Purita de la Rosa

(m. 1938; died 1943)

Eva Macaraeg

(m. 1946–1997)

Children

Ma. Cielo R. Macapagal-Salgado Arturo Macapagal Ma. Gloria M. Macapagal-Arroyo Diosdado M. Macapagal Jr.

Alma mater

University of the Philippines University of Santo Tomas

Profession

Lawyer Professor

Signature

Diosdado Pangan Macapagal Sr. GCrM (Tagalog pronunciation: [makapaˈɡal],[1] September 28, 1910 – April 21, 1997) was the ninth President of the Philippines, serving from 1961 to 1965, and the sixth Vice-President, serving from 1957 to 1961. He also served as a member of the House of Representatives, and headed the Constitutional Convention of 1970. He was the father of Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, who followed his path as President of the Philippines from 2001 to 2010. A native of Lubao, Pampanga, Macapagal graduated from the University of the Philippines and University of Santo Tomas, both in Manila, after which he worked as a lawyer for the government. He first won election in 1949 to the House of Representatives, representing a district in his home province of Pampanga. In 1957, he became vice president under the rule of President Carlos P. Garcia, whom he later defeated in the 1961 election. As President, Macapagal worked to suppress graft and corruption and to stimulate the Philippine economy. He introduced the country's first land reform law, placed the peso on the free currency exchange market, and liberalized foreign exchange and import controls. Many of his reforms, however, were crippled by a Congress dominated by the rival Nacionalista Party. He is also known for shifting the country's observance of Independence Day from July 4 to June 12, commemorating the day President Emilio Aguinaldo unilaterally declared the independence of the First Philippine Republic from the Spanish Empire in 1898. He stood for re-election in 1965, and was defeated by Ferdinand Marcos, who subsequently ruled for 21 years. Under Marcos, Macapagal was elected president of the Constitutional Convention which would later draft what became the 1973 Constitution, though the manner in which the charter was ratified and modified led him to later question its legitimacy. He died of heart failure, pneumonia, and renal complications, in 1997, at the age of 86. Macapagal was also a reputed poet in the Chinese and Spanish language, though his poetic oeuvre was eclipsed by his political biography.[citation needed]

Contents o o o o o o

1Early life 1.1Early education 1.2Early career 1.3First marriage 1.4Second marriage 2House of Representatives 3Vice presidency 4Presidency 4.1Cabinet 4.2Major legislation signed

o

4.3Domestic policies 4.3.1Economy 4.3.2Socio-economic program 4.3.3Land reform 4.3.4Anti-corruption drive 4.3.4.1Stonehill controversy 4.3.5Independence Day 4.4Foreign policies 4.4.1North Borneo claim 4.4.2Maphilindo 4.4.3Vietnam War 4.51963 midterm election 4.61965 presidential campaign 5Post-presidency and death 6Legacy 6.1Museum and library 7Electoral history 8Honors 9Publications 10See also 11References 12External links

o

o o o

Early life[edit] Diosdado Macapagal was born on September 28, 1910, in Lubao, Pampanga, the third of five children in a poor family.[2] His father was Urbano Macapagal y Romero (c. 1883 – 1946),[3] a poet who wrote in the local Pampangan language and his mother was Romana Pangan Macapagal, daughter of Atanacio Miguel Pangan (a former cabeza de barangay of Gutad, Floridablanca, Pampanga) and Lorenza Suing Antiveros. Urbano's mother, Escolastica Romero Macapagal is a midwife and schoolteacher who taught catechism.[4] Diosdado is a distant descendant of Don Juan Macapagal, a prince of Tondo, who was a great-grandson of the last reigning Lakan of the Kingdom of Tondo, Lakan Dula.[5] He is also related to well-to-do Licad family through Diosdado's mother Romana who is a second cousin of Maria Vitug Licad, grandmother of renowned pianist, Cecile Licad. Romana's grandmother, Genoveva Miguel Pangan and Maria's grandmother, Celestina Miguel Macaspac are siblings. Their mother, Maria Concepcion Lingad Miguel is a daughter of Jose Pingul Lingad and Gregoria Malit Bartolo. [6] Diosdado's family earned extra income by raising pigs and accommodating boarders in their home.[4] Due to his roots in poverty, Macapagal would later become affectionately known as the "Poor boy from Lubao".[7] Diosdado Macapagal was also a reputed poet in the Spanish language although his poet work was eclipsed by his political biography.

Early education[edit] Macapagal excelled in his studies at local public schools, graduating valedictorian at Lubao Elementary School, and salutatorian at Pampanga High School.[8] He finished his

pre-law course at the University of the Philippines, then enrolled at Philippine Law School in 1932, studying on a scholarship and supporting himself with a part-time job as an accountant.[4][8] While in law school, he gained prominence as an orator and debater. [8] However, he was forced to quit schooling after two years due to poor health and a lack of money.[4] Returning to Pampanga, he joined boyhood friend Rogelio de la Rosa in producing and starring in Tagalog operettas patterned after classic Spanish zarzuelas.[4] It was during this period that he married his friend's sister, Purita de la Rosa in 1938.[4] He had two children with de la Rosa, Cielo and Arturo.[7] Macapagal raised enough money to continue his studies at the University of Santo Tomas.[4] He also gained the assistance of philanthropist Don Honorio Ventura, the Secretary of the Interior at the time, who financed his education.[9] He also received financial support from his mother's relatives notably from the Macaspacs who owned large tracts of land in barrio Sta. Maria, Lubao, Pampanga. After receiving his Bachelor of Laws degree in 1936, he was admitted to the bar, topping the 1936 bar examination with a score of 89.95%.[8] He later returned to his alma mater to take up graduate studies and earn a Master of Laws degree in 1941, a Doctor of Civil Law degree in 1947, and a PhD in Economics in 1957. His dissertation had "Imperatives of Economic Development in the Philippines" as its title.[10]

Early career[edit] After passing the bar examination, Macapagal was invited to join an American law firm as a practicing attorney, a particular honor for a Filipino at the time.[11] He was assigned as a legal assistant to President Manuel L. Quezon in Malacañang Palace.[8] During the Japanese occupation of the Philippines in World War II, Macapagal continued working in Malacañan Palace as an assistant to President José P. Laurel, while secretly aiding the anti-Japanese resistance during the Allied liberation against the Japanese. [8] After the war, Macapagal worked as an assistant attorney with one of the largest law firms in the country, Ross, Lawrence, Selph and Carrascoso.[8] With the establishment of the independent Republic of the Philippines in 1946, he rejoined government service when President Manuel Roxas appointed him to the Department of Foreign Affairs as the head of its legal division.[7] In 1948, President Elpidio Quirino appointed Macapagal as chief negotiator in the successful transfer of the Turtle Islands in the Sulu Sea from the United Kingdom to the Philippines.[8] That same year, he was assigned as second secretary to the Philippine Embassy in Washington, D.C.[7] In 1949, he was elevated to the position of Counselor on Legal Affairs and Treaties, at the time the fourth-highest post in the Philippine Foreign Office.[12]

First marriage[edit] In 1938, he married Purita de la Rosa. They had two children, Cielo Macapagal-Salgado and Arturo Macapagal. Purita died in 1943.

Second marriage[edit] On May 5, 1946 he married Dr. Evangelina Macaraeg, with whom he had two children, Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo (who would become President of the Philippines) and Diosdado Macapagal, Jr.

House of Representatives[edit] On the urging of local political leaders of Pampanga province, President Quirino recalled Macapagal from his position in Washington to run for a seat in the House of Representatives representing the 1st District of Pampanga.[13] The district's incumbent, Representative Amado Yuzon, was a friend of Macapagal, but was opposed by the administration due to his support by communist groups.[13] After a campaign that Macapagal described as cordial and free of personal attacks, he won a landslide victory in the 1949 election.[13] He won re-election in the 1953 election, and served as Representative in the 2nd and 3rd Congress. At the start of legislative sessions in 1950, the members of the House of Representatives elected Macapagal as Chairman of the Committee on Foreign Affairs, and he was given several important foreign assignments.[12] He was a Philippine delegate to the United Nations General Assembly multiple times, notably distinguishing himself in debates over Communist aggression with Andrei Vishinsky and Jacob Malik of the Soviet Union.[12] He took part in negotiations for the U.S.-R.P. Mutual Defense Treaty, the Laurel–Langley Agreement, and the Japanese Peace Treaty.[8] He also authored the Foreign Service Act, which reorganized and strengthened the Philippine foreign service.[7] As a Representative, Macapagal authored and sponsored several laws of socioeconomic importance, particularly aimed at benefiting the rural areas and the poor. Among the pieces of legislation which Macapagal promoted were the Minimum Wage Law, Rural Health Law, Rural Bank Law, the Law on Barrio Councils, the Barrio Industrialization Law, and a law nationalizing the rice and corn industries. [8] He was consistently selected by the Congressional Press Club as one of the Ten Outstanding Congressmen during his tenure.[8] In his second term, he was named Most Outstanding lawmaker of the 3rd Congress .[8]

Vice presidency[edit] In the 1957 general election, the Liberal Party drafted Representative Macapagal to run for Vice President as the running-mate of José Yulo, a former Speaker of the House of Representatives. Macapagal's nomination was particularly boosted by Liberal Party President Eugenio Pérez, who insisted that the party's vice presidential nominee have a clean record of integrity and honesty.[13] While Yulo was defeated by Carlos P. Garcia of the Nacionalista Party, Macapagal was elected Vice President in an upset victory, defeating the Nacionalista candidate, José B. Laurel, Jr., by over eight percentage points. A month after the election, he was also chosen as the head of the Liberal Party. [9] As the first ever Philippine vice president to be elected from a rival party of the president, Macapagal served out his four-year vice presidential term as a leader of

the opposition. The ruling party refused to give him a Cabinet position in the Garcia administration, which was a break from tradition.[8] He was offered a position in the Cabinet only on the condition that he switch allegiance to the ruling Nationalista Party, but he declined the offer and instead played the role of critic to the administration's policies and performance.[7] This allowed him to capitalize on the increasing unpopularity of the Garcia administration. Assigned to performing only ceremonial duties as vice president, he spent his time making frequent trips to the countryside to acquaint himself with voters and to promote the image of the Liberal Party.[7]

Macapagal swears in as President of the Philippines at the Quirino Grandstand, Manila on December 30, 1961

As President, Macapagal worked to suppress graft and corruption and to stimulate the Philippine economy.

Presidency[edit] Presidental styles of

Diosdado P. Macapagal Reference style

His Excellency

Spoken style

Your Excellency

Alternative style

Mr. President

In the 1961 presidential election, Macapagal ran against Garcia's re-election bid, promising an end to corruption and appealing to the electorate as a common man from humble beginnings.[4] He defeated the incumbent president with a 55% to 45% margin. [7] His inauguration as the president of the Philippines took place on December 30, 1961.

Cabinet[edit] Office

Name

Term

President

Diosdado Macapagal

December 30, 1961 – December 30, 1965

Vice-President

Emmanuel Pelaez

December 30, 1961 – December 30, 1965

José Locsin

1961–1962

Benjamin Gozon

1962–1963

José Feliciano

1963–1965

Faustno SyChangco

February 15, 1960 – December 30, 1965

José E. Romero

December 30, 1961 – September 4, 1962

José Tuason

September 5, 1962 – December 30, 1962

Alejandro Roces

December 31, 1962 – September 7, 1965

Fernando Sison

January 2, 1962 – July 31, 1962

Rodrigo Pérez

August 1, 1962 – January 7, 1964

Rufino Hechanova

January 8, 1964 – December 13, 1965

Secretary of Agriculture and Natural Resources

Commissioner of Budget

Secretary of Educaton, Culture and Sports

Secretary of Finance

Emmanuel Pelaez

December 1961 – July 1963

Salvador P. Lopez

1963

Carlos P. Romulo

1963–1964

Mauro Mendez

May 1964 – December 30, 1965

Francisco Duque, Jr.

January 1962 – July 22, 1963

Floro Dabu

July 23, 1963 – March 6, 1964

Rodolfo Canos

May 1, 1964 – June 20, 1964

Manuel Cuenco

December 13, 1964 – December 29, 1965

Jose W. Diokno

January 1962 – May 1962

Juan Liwag

May 1962 – July 1963

Salvador Mariño

July 1963 – December 1965

Secretary of Natonal Defense

Macario Peralta, Jr.

December 30, 1961 – December 30, 1965

Secretary of Commerce and Industry

Manuel Lim

1961–1962

Rufino Hechanova

1962–1963

Secretary of Foreign Affairs

Secretary of Health

Secretary of Justce

Cornelio Balmaceda 1963–1965

Marciano Bautsta

1961–1962

Paulino Cases

1962

Brigido Valencia

1962–1963

Jorge Abad

1963–1965

Sixto Roxas

1963

Claudette Caliguiran

1963–1964

Benjamin Gozon

1964–1965

Secretary of Public Works, Transportaton and Communicatons

Secretary of Agrarian Reform

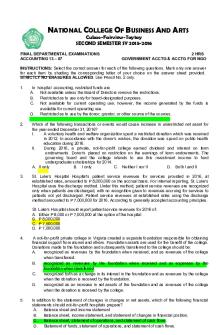

Major legislation signed[edit]

Republic Act No. 3512 – An Act Creating A Fisheries Commission Defining Its Powers, Duties and Functions, and Appropriating Funds Therefore. Republic Act No. 3518 – An Act Creating The Philippine Veterans' Bank, and For Other Purposes. Republic Act No. 3844 – An Act To Ordain The Agricultural Land Reform Code and To Institute Land Reforms In The Philippines, Including The Abolition of Tenancy and The Channeling of Capital Into Industry, Provide For The Necessary Implementing Agencies, Appropriate Funds Therefor and For Other Purposes. Republic Act No. 4166 – An Act Changing The Date Of Philippine Independence Day From July Four To June Twelve, And Declaring July Four As Philippine Republic Day, Further Amending For The Purpose Section Twenty-Nine Of The Revised Administrative Code. Republic Act No. 4180 – An Act Amending Republic Act Numbered Six Hundred Two, Otherwise Known As The Minimum Wage Law, By Raising The Minimum Wage For Certain Workers, And For Other Purposes.

Domestic policies[edit] Economy of the Philippines under

President Diosdado Macapagal 1961–1965 Population 29.20 million

1962

Gross Domestic Product (1985 constant prices) 1962

Php 234,828 million

1965

Php 273,769 million

Growth rate, 1962-65

5.5 % Per capita income (1985 constant prices)

1962

Php 8,042

1965

Php 8,617

Total exports 1962

Php 46,177 million

1965

Php 66,216 million

Exchange rates 1 US$ = Php 3.80 1 Php = US$ 0.26 Sources: Philippine Presidency Project Malaya, Jonathan; Eduardo Malaya. So Help Us God... The Inaugurals of the Presidents of the Philippines. Anvil Publishing, Inc.

Economy[edit]

In his inaugural address, Macapagal promised a socio-economic program anchored on "a return to free and private enterprise", placing economic development in the hands of private entrepreneurs with minimal government interference.[7]

Twenty days after the inauguration, exchange controls were lifted and the Philippine peso was allowed to float on the free currency exchange market. The currency controls were initially adopted by the administration of Elpidio Quirino as a temporary measure, but continued to be adopted by succeeding administrations. The peso devalued from P2.64 to the U.S. dollar, and stabilized at P3.80 to the dollar, supported by a $300 million stabilization fund from the International Monetary Fund.[7] To achieve the national goal of economic and social progress with prosperity reaching down to the masses, there existed a choice of methods. First, there was the choice between the democratic and dictatorial systems, the latter prevailing in Communist countries. On this, the choice was easy as Filipinos had long been committed to the democratic method.[14] With the democratic me...

Similar Free PDFs

Diosdado Macapagal - This is helpful

- 24 Pages

Joseph estrada - This is helpful

- 20 Pages

3 - this is courswork

- 5 Pages

This is for Handout

- 4 Pages

2 - this is courswork

- 6 Pages

Strar cost - This is

- 9 Pages

2 - this is courswork

- 7 Pages

A3F332C56850 - this is me

- 9 Pages

Outcomes - this is outcome

- 16 Pages

bruh wtf is this

- 2 Pages

Popular Institutions

- Tinajero National High School - Annex

- Politeknik Caltex Riau

- Yokohama City University

- SGT University

- University of Al-Qadisiyah

- Divine Word College of Vigan

- Techniek College Rotterdam

- Universidade de Santiago

- Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Johor Kampus Pasir Gudang

- Poltekkes Kemenkes Yogyakarta

- Baguio City National High School

- Colegio san marcos

- preparatoria uno

- Centro de Bachillerato Tecnológico Industrial y de Servicios No. 107

- Dalian Maritime University

- Quang Trung Secondary School

- Colegio Tecnológico en Informática

- Corporación Regional de Educación Superior

- Grupo CEDVA

- Dar Al Uloom University

- Centro de Estudios Preuniversitarios de la Universidad Nacional de Ingeniería

- 上智大学

- Aakash International School, Nuna Majara

- San Felipe Neri Catholic School

- Kang Chiao International School - New Taipei City

- Misamis Occidental National High School

- Institución Educativa Escuela Normal Juan Ladrilleros

- Kolehiyo ng Pantukan

- Batanes State College

- Instituto Continental

- Sekolah Menengah Kejuruan Kesehatan Kaltara (Tarakan)

- Colegio de La Inmaculada Concepcion - Cebu