Exemption clauses PDF

| Title | Exemption clauses |

|---|---|

| Author | Selvaggia Pianetti Lotteringhi |

| Course | Elements Of The Law Of Contract |

| Institution | King's College London |

| Pages | 14 |

| File Size | 254.1 KB |

| File Type | |

| Total Downloads | 70 |

| Total Views | 182 |

Summary

Notes concerning the exemption clauses in contract law. ...

Description

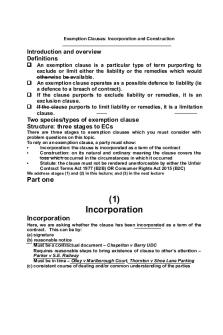

CONTENTS 2: EXEMPTION CLAUSES

1. WHAT IS AN EXEMPTION CLAUSE? It is a term of a contract under which one of the parties restricts his liability. There are two types of exemption clauses: exclusion clauses and limitation clauses. a. Exclusion clause With an exclusion clause, one party excludes his liability - a party can exclude any tortious liability (ex: contract of carriage - carrier can exclude liability for damage) b. Limitation clause Instead of excluding the liability, it limits the parties right to sue for negligence - ex limit the amount of damages that the other party will receive. It can also restrict the other party's right … or by stipulating that the seller will give replacement goods instead of paying damages c. Standard forms of contract Standard forms of contract is an agreement freely negotiated between the parties which has given way to a uniform set of printed conditions which can be used time and time again and for a large number of persons. Standard forms of contract are also called contrat d’adhésion. E.g.: when someone takes the bus, the supplier (in this instance, the bus company) will devise a standard form of contract which the individual must either accept whole or go without. The individual does not negotiate, but merely adheres to a standard form of contract. The contracting party thus has the status of a consumer. d. Regulation of exemption clause If parties don't have the same bargaining power, one party can impose terms on the other party through the use of standard forms of contract, which incorporate the standard terms and conditions of the company. It imposes certain requirements and construes the document in favour of the party wishing to enforce it. The means of protection at common law are pretty slender. However, the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977 and the Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations Act 1999 have increased the power of the courts to control exemption clauses and redress the balance in favour of individuals.

2. REGULATION AT COMMON LAW a. Incorporation Exemption clauses are only operative if they are incorporated in a contract.

(a) Signature Where C has signed the exemption clause, it immediately becomes binding. However, there are three exceptions to that: where the signature is induced by misrepresentation or fraud, where non est factum applies and where the signed document does not purport to have contractual effect. L'Estrange v Graucob [1934]: C bought an automatic slot machine. C signed an order firm that, in its fine prints, excluded all liability. C didn't read the form but it was held that if the document was signed, C was therefore bound. The only exception is if it was a misrepresentation or fraud. Curtis v Chemical Cleaning & Dyeing Co [1951]: C took a dress to D’s company for cleaning. She signed a receipt containing a clause exempting D from all liability for damage to articles cleaned. She did so after D’s servant told her that it would not accept liability for certain specified risks, including damage to beads and sequins on the dress. When it was returned, the dress was badly stained. Held – It was held that C had been induced by misrepresentation to believe that the clause only referred to the beads and sequins. Any behaviour, by word or conduct is sufficient to be a misrepresentation if it is such as to mislead the other party about the existence or extent of the exemption. (b) Notice If a document is not signed but merely delivered, was the term adequately brought to the notice of the contracting party? Notice must be contemporaneous with contract: Where there is no signature, a term becomes binding when it is brought to the notice of the other contracting party before or at the time the contract is made. Olley v Marlborough Court Ltd [1949]: C booked into a hotel and a contract was formed at the reception desk. In his room, he saw a notice on the bedroom door that said that the hotel was not liable for loss of property. Due to the negligence of the hotel staff, a thief got access to C’s room and stole some of his property. Held – the CoA found that the notice did not form part of the contract as C was only made aware of it after the contract was made. Therefore, D was liable. Thornton v Shoe Lane Parking [1971]: C parked his car in a garage and received at the entrance a ticket from an automatic machine. Held - the CoA found that the customer was not bound by the conditions on the ticket because the machine dispensed the ticket while the car was being driven to the garage and C could not be affected by conditions brought to his notice after this time. Non-contractual documents: Chapelton v Barry UDC [1940] C hired a deck chair at the beach from D. He received a ticket in return for payment. C went through the canvas and sued D for personal injuries. An exemption clause printed at the back of the ticket said that the Council was not responsible for any damages. C had not realised that the notice had contained conditions. Held – The CoA held that this would the type of document that someone would hardly expect to have conditions, and as such D was not protected.

"Reasonable sufficiency of notice": When will a party receiving a ticket, receipt, etc. be bound by the conditions contained on it? Three general rules have been laid down to determine whether or not C will be bound: A person receiving a ticket who did not see or know that there was any writing on the ticket will not be bound by the conditions A person who knows there was writing, and knows or believes that the writing contained conditions, is bound by the conditions A person who knows that there was writing on the ticket, but does not know or believe that the writing contained conditions, will nevertheless be bound where the delivery of the ticket, in such manner that the writing on it could be seen, is reasonable notice that the writing contained conditions Parker v South Eastern Railway Co [1877]: C deposited his bag worth 24 pounds in the cloakroom of a railway station. He received a ticket with the opening hours and it said "see back” where a number of conditions were listed. C argued that he knew there was writing on the ticket but stated that he had not read it and did not know or believe that the writing contained conditions. Held - the CoA held that the issue of the case was whether D had done what was reasonably sufficient to give C notice of the conditions. CoA ordered a new trial Objective test of reasonable sufficiency of notice. That test has to be applied within the facts of a particular case. The courts thus need to look at all the circumstances and the situation of the parties. Thompson v LMS Railway [1930] C was illiterate. She gave her niece the money for the ticket. The ticket said see back for conditions and the back said see timetable for conditions. C was injured by D’s alleged negligence. Held – The CoA said that the exemption clause was incorporated since the ticket referred to the timetable where the exemption clause was printed. As such, reasonable notice was given and D was held not liable. The fact C was illiterate was irrelevant. Exhibited notice: printed notice containing conditions (e.g. notices exhibited at counters) have been held to become part of the contract where the ticket or receipt refers to the notice and probably even where it does not, provided that the notice is sufficiently prominent and can plainly be seen before or at the time the contract is made. "Onerousness" of exemption clauses: Degree of notice will increase according to the unusualness of the condition. Thornton v Shoe Lane Parking [1971]: it was held that where a condition is particularly onerous or unusual, the party has to show that the condition was fairly brought to the notice of the other party. Interfoto Picture Library Ltd v Stiletto Visual Programmes Ltd [1989]: Interfoto hired 47 transparencies to Stiletto. The transparencies were delivered with a note containing conditions on the face of the document. One condition stated that a holding fee of 5 pounds would be charged per day per transparency retained for longer than 14 days. The daily rate per transparency was many times greater than usual and yet Interfoto didn’t do

anything to bring it to Stiletto’s attention. Held – The CoA held that if the condition was particularly onerous the party wishing to enforce it must show that it had been fairly brought to the attention of the other party. In this case, Interfoto hadn't done that. Inferring notice of an exemption clause: this can happen, where there has been a previous dealing between the parties. However, before the exemption clause was implied, the contract would have to have been made in exactly the same way as before. (c) Course of dealing An exemption clause will not necessarily be incorporated into a contract by virtue of a previous course of dealing between the same parties on similar terms. McCutcheon v MacBrayne [1964]: C sought damages in respect of his loss when D’s ferry sank, losing his shipment. Usually, D required the signature of a note to exempt him of liability. However, on this occasion, C’s brother in law had arranged the shipment and had not signed the note. C had already dealt with D on four previous occasions and his brother in law as well. D argued that although the note had not been signed, the term excluding liability had been incorporated into their contract through a course of dealing. Held – The House of Lords found that there was no regular course of dealing with C and no consistent course of dealing with C’s brother in law. Hence, the term had not been incorporated. Hollier v Rambler Motors (AMC) Ltd [1972]: C took his car for repair at D’s garage. He had already been there on 4 occasions: twice he had signed an invoice excluding liability for damage caused by fire and twice hadn’t. C did not sign the form on this occasion and a fire broke out in the garage, damaging his car. Held – The CoA found that the previous course of dealing had not incorporated the term, as it was neither regular nor consistent. It also went on to say that had the exclusion clause been incorporated it still would not have been effective as the clause exempted liability for its own mistakes and not just things beyond its control. (D could not exclude himself from liability). b. Construction of Exemption Clauses Assuming that the exemption clause was incorporated into the contract, the next issue is to determine in which way should the terms of the contract be construed. Is the exemption clause sufficiently general to cover the breach that has occurred? (a) Strict interpretation The words of the exemption clause must exactly cover the situation: e.g. a clause excluding liability for breach of warranty will not exclude liability for a breach of condition. Wallis, Son & Well v Pratt & Haynes [1911]: C bought seeds from D which were subject to an exemption clause that ’the sellers give no warranty express or implied, as to growth, description, or any other matters.' The seed that they supplied was of inferior quality and of less value. C was therefore forced to compensate those to whom he had subsequently sold the seed to and sued D to recover the money lost. D pleaded the exemption clause. Held - the House of Lords held that even though C had accepted the goods and could therefore only sue for breach of warranty, there was initially a breach of the condition

implied by s13 of the Sale of Goods Act. The condition had not been successfully excluded and thus D was liable. (b) "Contra proferentem" rule It is the principle whereby the words of written documents are construed more forcibly against the party seeking to enforce the exemption clause. This rule is only applied when there is doubt or ambiguity in the phrases used. (c) Exclusion of liability for negligence Excluding liability for negligence has been substantially restricted by legislation (UCTA s2 and UTCCR, schedule 2, para 1(a)) Although it is possible to exclude liability in negligence, the courts operate on the assumption that it is improbable that the innocent party would have agreed to the exclusion of the contract-breaker’s negligence. The courts expressed three specific rules of construction: 1. If the clause clearly and unambiguously exempts the person relying on it, an effect must be given to that provision. Rutter v Palmer [1922]: C left his car at D’s garage to be sold. The contract provided that C’s car would be driven by D at C’s sole risk. The car was taken for a trial run by one of D’s drivers. There was a collision and C’s car was damaged. Held – The clause placed the risk of negligence on C and thus D was exempt from liability. 2. The courts must consider if the words are wide enough to cover negligence. If there is a doubt, it must be resolved against the party seeking the enforcement of the exemption clause. 3. The courts need to consider whether the exemption clause may also cover some kind of liability other than negligence. If there is such liability, the clause will be construed as confined in its application to that confined liability and will not extend to negligently affected loss. Canada Steamship Lines Ltd v The King [1952]: A lease of a freight shed provided that the lessee should ‘not have any claim against the lessor for damage to goods’ in the shed. Owing to the negligence of the lessor’s employee, a fire broke out and the lessee’s goods in the shed were destroyed. Held – the Privy Council held that a strict liability was imposed by the Civil Code of Quebec and because of that, the exemption clause should be confined to that head of liability. D was therefore liable for the negligent destruction of the goods. Strict liability imposed on the lessor. Hollier v Rambler Motors (AMC) Ltd [1972]: see facts above. It was held that the language of the clause did not exclude liability for negligence.

(d) Limitation clauses A less rigorous approach governs clauses that merely limit the compensation payable but do not totally exclude liability. Alisa Craig Fishing Co Ltd v Malvern Fishing Co Ltd [1983]: The House of Lords held that, limitation clauses should not be given a restricted meaning but their natural meaning.

The contra preferentum rule should not apply as strictly to limitations clauses. (e) Fundamental breach Previously, there was the common law doctrine of fundamental breach. There were, in every contract, certain terms which were fundamental, the breach of which amounted to a complete non-performance of the contract. This doctrine was a rule of construction not a rule of law. It was sustained until the Suisse Atlantique case. Suisse Atlantique Société d'Armement Maritime SA v NV Rotterdamsche Kolen Centrale [1967]: SA chartered the Silvretta to RKC for a period of 2 years. It was agreed that, in the event of delays in loading or unloading the vessel, RKC would pay SA $1,000 a day by way of demurrage. Lengthy delays occurred for which SA alleged RKC was responsible, but it nevertheless allowed RKC to continue to have the use of the ship for the remainder of the term. On conclusion of the contract, SA sued RKC for damages, claiming a sum in excess of that stipulated for demurrage. RKC relied on its demurrage clause to limit its liability. Held – The House of Lords held that the demurrage clause was not an exemption clause but an agreed damages provision. Nevertheless, had it been an exemption clause, it covered the breaches which had occurred. Even if the breaches amounted to a fundamental breach of contract, there was no rule of law which would prevent the application of the exemption clause to such a breach. Photo Production Ltd v Securicor Transport Ltd [1980]: D agreed to provide a visiting patrol service to C’s factory at a charge of 26p per visit. The contract contained an EC which stated that the company would not be responsible for any act or default by any employee unless it could have been foreseen and avoided by the exercise of due diligence. C’s employee, while on patrol, deliberately lit a fire in the factory. Held – The House of Lords found that D was absolved of liability as there was no evidence of any lack of due diligence on its parts to foresee or prevent the fire. It was reaffirmed in this case that the question of whether or not an EC protected a party to a contract in the event of a breach depended on the construction of the contract. The need for a substantive doctrine of fundamental breach has been obviated by the UCTA.

(f ) Express oral promise contrary to written exemption clause Where an express undertaking is given, J. Evans & Son (Portsmouth) Ltd v Andrea Merzario Ltd [1976]: it was held that D's oral insurance that machines shipped on deck would … D was liable for breach of warranty given.

3. STATUTORY REGULATION 1: THE UNFAIR CONTRACT TERMS ACT 1977 (UCTA) a. Introduction The purpose of the 1977 Act is to limit or sometimes take away entirely the right to rely on exemption clauses in certain situations. The act is concerned with the kind of situations

where a business attempts to exclude or limit liability through the use of an exemption clause. 1977 Act is not confined to contract terms; it also extends to non-contractual notices. Notices that contain provisions exempting from liability in tort. For example, if A, a surveyor, has a contract with B excluding liability for negligence, then the act will apply. The Act will also apply if A allows that survey to be used by C, with whom he has no contract but has attempted to exclude liability for negligence in a noncontractual notice to C. The Act does not apply to all unfair terms. It applies to those terms that exclude or restrict liability. It only applies to exemption clauses. Steps in analysing exemption clauses: • Test of incorporation: does the exemption clause form a part of the contract? • Construction: does it cover events that have occurred? • Then is it fair and enforceable under UCTA? • Do the Unfair Terms and Consumer Regulations apply? Pattern of control: there are 3 broad divisions of control. - Negligence: form of control over contract terms that exclude or restrict liability for negligence. Includes breach of a contractual duty to exercise reasonable care and skill in the performance of a contract (s 2) - Breach of contract: control also extends to breaches of contract. Control in consumer contracts and standard form contracts (s 3) - Sale of goods, hire purchase: control over contract terms that exclude or restrict liability for breach of certain terms implied by statute in contracts of sale of goods and hire purchase and other contracts for the supply of goods (s 6 and 7) b. Is the exemption clause enforceable under UCTA? (a) Preliminary issues (i) Excepted contracts Ss.26-29 and Schedule 1 - contracts which UCTA does not apply e.g. s26 - Internal Supply Contracts: these are very important contracts that are wholly or partially exempted from the operation of the act. E.g. Contracts of Insurance Commercial, Charter Parties, Contracts for the carriage of goods by sea, International Supply Contracts, Contracts of employment. Many others exist. However, in many of these, what you have is a specific form of legislative control on that kind of exemption clause in question and in the case of consumer contracts some of these will be subject to the Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations 1999. (ii) ‘Business liability’ Is the defendant’s potential liability to the claimant a business liability? D’s potential liability must be business liability. Contracts made in the course of a business where it is integral to the business or forms part of the regular course of dealings of that business.

Deals as a consumer: As a general rule the Act provides greater protection to a person who deals as a consumer than to one that does not. To deal as a consumer C must satisfy two conditions: 1. The party must not have made the contract in the course of a business (s.12(1)(a)) 2. The other party must have made the contract in the course of a business.

(iii) Variety of exemption clauses S.13 - “varieties of exemption clause” The Act only applies to contract terms excluding or restricting liability, but s.13(1) extends these to (a) those creating restrictive or onerous conditions, (b) ex...

Similar Free PDFs

Exemption clauses

- 14 Pages

Exemption Clauses

- 2 Pages

Exemption Clauses - Lecture notes 10

- 17 Pages

Medi Care Levy Exemption

- 3 Pages

SUBORDINATE CLAUSES

- 2 Pages

Clauses abusives

- 1 Pages

Subordinate Clauses

- 1 Pages

Adverbial clauses

- 4 Pages

Relative Clauses

- 4 Pages

Exemption Clause part 1

- 7 Pages

Actuarial studies exemption guide

- 28 Pages

IF-clauses-2021 - Ras

- 1 Pages

Relative clauses theory

- 4 Pages

Popular Institutions

- Tinajero National High School - Annex

- Politeknik Caltex Riau

- Yokohama City University

- SGT University

- University of Al-Qadisiyah

- Divine Word College of Vigan

- Techniek College Rotterdam

- Universidade de Santiago

- Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Johor Kampus Pasir Gudang

- Poltekkes Kemenkes Yogyakarta

- Baguio City National High School

- Colegio san marcos

- preparatoria uno

- Centro de Bachillerato Tecnológico Industrial y de Servicios No. 107

- Dalian Maritime University

- Quang Trung Secondary School

- Colegio Tecnológico en Informática

- Corporación Regional de Educación Superior

- Grupo CEDVA

- Dar Al Uloom University

- Centro de Estudios Preuniversitarios de la Universidad Nacional de Ingeniería

- 上智大学

- Aakash International School, Nuna Majara

- San Felipe Neri Catholic School

- Kang Chiao International School - New Taipei City

- Misamis Occidental National High School

- Institución Educativa Escuela Normal Juan Ladrilleros

- Kolehiyo ng Pantukan

- Batanes State College

- Instituto Continental

- Sekolah Menengah Kejuruan Kesehatan Kaltara (Tarakan)

- Colegio de La Inmaculada Concepcion - Cebu