A Small Place PDF

| Title | A Small Place |

|---|---|

| Course | StuDocu Summary Library EN |

| Institution | StuDocu University |

| Pages | 10 |

| File Size | 169 KB |

| File Type | |

| Total Downloads | 43 |

| Total Views | 167 |

Summary

A Small Place...

Description

A Small Place - Jamaica Kincaid Context Elaine Potter Richardson, who later became the novelist and essayist Jamaica Kincaid, was born in 1949 in St. John’s, the capital city of the Caribbean island of Antigua. By Kincaid’s own account, she was a highly intelligent but often moody child, and she became increasingly distant from her mother as the family grew in number—an estrangement that would later become a central theme in her fiction. As she matured, Kincaid also became estranged from the social and cultural milieu in which she found herself. Too ambitious and intellectually curious to be satisfied with her career prospects in her tiny island home, she was also becoming alienated from the mostly white, European tradition handed down to her through her colonial education. At seventeen, Kincaid moved to New York to work as an au pair while continuing her studies, eventually earning a scholarship to Franconia College in New Hampshire. Dissatisfied, she left school after a year and moved back to Manhattan, where she began working as a magazine and newspaper features journalist. During this period, Elaine Richardson changed her name to Jamaica Kincaid in a symbolic act of self-definition and freedom from the “weights” of personal and political history. As Kincaid herself put it in an interview with the New York Times Magazine, the new name represented “a way for me to do things without being the same person who couldn’t do them—the same person who had all these weights.” Kincaid’s big break came when she was hired as a staff writer by The New Yorker, and the magazine’s editor, William Shawn (famous as a judge of talent and an exacting critic of prose) became her mentor. Kincaid’s first book of short stories, At the Bottom of the River, was published in 1983, and her first novel, Annie John, followed two years later. Kincaid’s early fiction, such as the much-anthologized story “Girl,” often focuses on the mental world of a young girl much like the young Kincaid, with particular attention to the nuances and rhythms of Caribbean English. This evocation of the speech of the islands is reminiscent of the poetry of Derek Walcott (of St. Lucia) and Edward Kamau Brathwaite (of Barbados), and the stories of At the Bottom of the River have often been compared to prose poems. Kincaid’s treatment of the lingering effects of slavery and colonialism on the minds of those descended from slaves and from the once-colonized Caribbean “natives” places her in the company of the Trinidadian novelist V. S. Naipaul and the

Dominican novelist Jean Rhys, as well as the poets just mentioned. However, Kincaid’s primary allegiance in her fiction—more than any affinity she might have to a movement or school of writing—is to her own vision and voice. In addition to her fiction, Kincaid has produced a steady stream of nonfiction, beginning with her brief “Talk of the Town” pieces for The New Yorker and continuing more recently with her essays on gardening for the same magazine. A Small Place was, in fact, first meant for The New Yorker, but it was rejected as too harsh and angry in tone. The essay has been controversial since it first appeared in book form in 1988. Since then, it has gradually found its place within the English tradition of anticolonial travel writing, a tradition stretching back to Jonathan Swift’s mercilessly satirical writings on Ireland in the eighteenth century and including George Orwell’s classic essay “Shooting an Elephant,” as well as works by such writers as Graham Greene and the American Paul Theroux. Kincaid’s essay has also been important to “postcolonial” theory, a branch of literary studies that is concerned with understanding how a colonized people both internalizes and resists the colonizing culture. A Small Place has come to be seen as a perfect example of a postcolonial text: in it, a former colonial subject turns the greatest tools of empire, culture, and language into weapons directed against imperialism itself.

Plot Overview A Small Place is divided into four loosely structured, untitled sections. The first section begins with Kincaid’s narration of the reader’s experiences and thoughts as a hypothetical tourist in Antigua. The reader, through Kincaid’s description, witnesses the great natural beauty of the island, while being sheltered from the harsher realities of the lives of those who must live there. Kincaid weaves into her narrative the sort of information that only an “insider” would know, such as the reason why the majority of the automobiles on the island are poorly running, expensive Japanese cars. Included in her guided tour are brief views of the mansions on the island, mostly gained through corruption or outright criminality. She also mentions the now-dilapidated library, still awaiting repairs after an earthquake ten years earlier. The tour continues at the hotel, and Kincaid concludes the section with a discussion of her view of the moral ugliness of being a tourist. The second section deals with Kincaid’s memories of the “old” Antigua, the colonial possession of Great Britain. Kincaid recalls the casual racism of the times, and the subservience of Antigua to England and, especially, to English

culture. She delves briefly into the history of Barclay’s Bank and discusses the Mill Reef Club, an elite, all-white enclave built by wealthy foreigners. She describes and deplores the great hoopla made over the visit of Princess Margaret to the island when Kincaid was a child. Much of the section is concerned with the distortions that colonialism has created in the minds of the Antiguans; Antiguans do not tend to recognize racism as such, says Kincaid, and the bad behavior of individual English people never seems to affect the general reverence for English culture. For Kincaid, the problem is compounded by the fact that the people of Antigua can express themselves only in the language of those who enslaved and oppressed them. She then discusses the connection she sees between the colonial past of the island and its impoverished, corrupt present. The third section, the longest, deals with Antigua’s present and begins with Kincaid asking herself the disturbing question of whether, considering the state of the island today, things weren’t, in fact, better in the old days. As an example, she takes the state of the library, awaiting repairs after all these years and forced to reside in “temporary” quarters above a dry goods store. Kincaid has fond, if ambivalent, feelings toward the old library, which was a haven of beauty and an escape into reading for her as a child. She recalls the imperious ways of the head librarian (who suspected Kincaid, rightly, of stealing books), who is now sadly reduced to campaigning, mostly unsuccessfully, for funds to build a new library, while the collection decomposes in cardboard boxes. The rich members of the Mill Reef Club have the funds to help, but will do so only if the old library is rebuilt—a demand that Kincaid sees as having more to do with nostalgia for the colonial regime than with a true desire to help. Kincaid mentions the ironies involved in Antigua having a Minister of Culture without having a culture to administer. She also mentions her politically active mother’s run-in with the current Minister of Culture, who has allowed the library to languish. Education has clearly suffered on Antigua in the years since independence, and Kincaid ruefully notes the poor speech habits of the younger Antiguans. Kincaid discusses the way Antiguans experience the passage of time, and connects this to their oddly detached view of the corruption of their government. She then goes into a litany of the many abuses of power on the island, including misappropriation of funds, kickbacks, drug smuggling, and even political violence—all of which are known by the average Antiguan. Kincaid then discusses the political history of Antigua since independence,

showing how power has rested in the same hands for most of the period, with one brief, unimpressive exception. Kincaid sees corruption as an ingrained element of political life on the island, so much so that government officials who do not steal are held in contempt as fools rather than admired for their honesty. She tells of the fears that many Antiguans have for the future and hints that open dictatorship or political upheaval may lie ahead. The fourth, and final, section is a sort of coda to the piece, starting with an evocation of the intense physical beauty of the island. She describes the beauty as so extreme as to appear “unreal,” almost like an illustration or a stage-set. Kincaid says that the beauty of their surroundings is a mixed blessing to the Antiguans, who are trapped in an unchanging setting in which their poverty is part of the scenery. The slaves who were brought to Antigua by force were victims, and therefore noble—but their descendants, today’s Antiguans, are simple human beings, with all the problems and contradictions of human beings anywhere.

Character list V. C. Bird - The first post independence Prime Minister of Antigua, and, with the exception of one five-year term, the only one. The Antigua airport is named for V. C. Bird. He is the head of an extremely corrupt government, and his sons are poised to take his place once he dies. This, along with the facts that Antigua has a standing army with nothing to do and that the government controls the media, leads Kincaid to worry about the long-term viability of democracy on the island. The Head Librarian - An imposing figure in the life of the young Jamaica Kincaid. The head librarian holds a culturally prestigious post, though a diminished one now. At one time, she worked in the beautiful old library in the central part of town. After an earthquake destroyed the library, the collection moved to “temporary” quarters—for over ten years. The head librarian’s struggles to raise money for a new library, and her makeshift bookroom above a dry goods store, render her a sad figure of the decline of the already meager cultural institutions on Antigua. The Irish Headmistress - A twenty-six-year-old woman recruited by the Colonial Office in England to run the girl’s school in Antigua. The headmistress often rebuked the girls by telling them to stop behaving “as if they were monkeys just out of the trees.” Her thoughtless racism is

emblematic of the callousness of colonial rule and of the passivity of the Antiguans when faced with it. Jamaica Kincaid - The author and narrator of A Small Place. Kincaid makes use of personal experience and history in the essay, and the entire work is permeated with her anger and intelligence. Kincaid emerges as a character both as a young girl, desperate for knowledge and a wider world, and as an adult, looking at her birthplace with a ruthlessly penetrating eye. Kincaid’s Mother - The author’s mother. Kincaid’s mother appears briefly in an anecdote that Kincaid tells about her political activity. Her brash opinions and loud mouth earn her a reputation as a troublemaker, and the Minister of Culture is not pleased to find her posting signs for the opposition party in front of his house. When he tries to snub her, Kincaid’s mother implies that he is a crook and that she knows all about it; the Minister retreats. Even in this brief scene, Kincaid’s admiration for and ambivalence toward her formidable mother are clear. The “Other Prime Minister” - The man, unnamed by Kincaid, who supplants Bird for one term. This Prime Minister campaigns as an enlightened democrat and promises to fight corruption. There are stories of dishonesty in his own past, including one that he destroyed the accounting books of one of his employers to hide his embezzlement. The great optimism that greets his election is soon quenched by the incompetence of his administration, and he is jailed after losing the next election. Princess Margaret - The younger sister of the future queen of England, Elizabeth II. Margaret makes a state visit to Antigua when Kincaid is a child. The entire island is spruced up for her arrival, and the princess is greeted by crowds who regard the visit as one of the great events in Antigua’s history. Years later, Kincaid learns that, far from being motivated by any particular interest in Antigua or the Antiguans, Margaret had simply been trying to escape a sticky personal situation back in England—she had fallen in love with a married man. The Syrians - Foreigners who have moved to Antigua to make their fortunes in business speculation. To the Antiguans, the Syrians are involved in most of the corruption on the island. Kincaid points out that they have connections high in the government and that they have become fabulously wealthy by renting properties to the government at exorbitant prices. She also implies that the Syrians may be involved in politically and economically motivated

violence, such as the strange deaths-by-electrocution that befall certain officials. The Woman from the Mill Reef Club - A wealthy woman Kincaid speaks to regarding the rebuilding effort for the library. This unnamed woman is wellknown for her dislike of the Antiguans in any role except that of a servant. She encourages “her girls” (employees) to use the library and wants to rebuild it just as it was before the earthquake. Kincaid sees her as motivated by nostalgia for the days of colonial rule and resents the woman’s smirking at the corruption of the post-independence government, though she also resents the accuracy of the charge. “You” - The personified reader whom Kincaid addresses throughout the essay. Especially in the first section, “you,” the reader, is characterized as a basically ordinary, middle-class American or European, mostly ignorant of Antigua’s history and of the lives of its inhabitants. “You” becomes the main focus of Kincaid’s attack on what she sees as the moral ugliness of tourism.

Themes, Motifs, and Symbols Themes THE UGLINESS OF TOURISM

For Kincaid, tourists are morally ugly, though in her description of fat, “pastrylike-fleshed” people on the beach, she shows that physical ugliness is part of tourism as well. The moral ugliness of tourism is inherent in the way tourists make use of other, usually much poorer, people for their pleasure. Kincaid is not referring to direct exploitation of others (though she does mention one government minister who runs a brothel); rather, she refers to a more spiritual form of exploitation. According to Kincaid, a tourist travels to escape the boredom of ordinary life—they want to see new things and people in a lovely setting. Kincaid points out that the loveliness of the places that tend to attract tourists is often a source of difficulty for those who live there. For example, the sunny, clear sky of Antigua, which indicates a lack of rainfall, makes fresh water a scarce and precious commodity. For tourists, however, the beauty is all that matters—the drought is someone else’s problem.

Others’ problems can even add to the attraction of a place for tourists. Kincaid notes that tourists tend to romanticize poverty. The locals’ humble homes and clothing seem picturesque, and even open latrines can seem pleasingly “close to nature,” unlike the modern plumbing at home. Kincaid believes that this attitude is the essence of tourism. The lives of others, no matter how poor and sad, are part of the scenery tourists have come to enjoy, a perspective that negatively affects both tourists and locals. The exotic and often absurd misunderstanding that tourists have of a strange culture ultimately prevents them from really knowing the place they have come to see. ADMIRATION VS. RESENTMENT OF THE COLONIZER

Kincaid observes the quality of education on Antigua, as well as the minds of its inhabitants, and remains deeply ambivalent about both. She herself is the product of a colonial education, and she believes that Antiguan young people today are not as well-educated as they were in her day. Kincaid was raised on the classics of English literature, and she thinks today’s young Antiguans are poorly spoken, ignorant, and devoted to American pop culture. However, one of the things Kincaid despises most about the old Antigua was its cultural subservience to England. If young Antiguans today are obsessed with American trash, in the old days they were obsessed with British trash. One of the insidious effects of Antiguans being schooled in the British system is that all of their models of excellence in literature and history are British. In other words, Antiguans have been taught to admire the very people who once enslaved them. Kincaid is horrified by the genuine excitement the Antiguans have regarding royal visits to the island: the living embodiment of British imperialism is joyously greeted by the former victims of that imperialism. Antiguans’ minds have been shaped from the bottom up by the experience of being enslaved and, later, colonized. This intimate shaping determines the contours of daily life and even private thoughts. For example, the young Kincaid’s greatest pleasure is in reading, but everything she reads is tainted by bitterness, since she is learning the dominant culture from the position of a dominated people. English is her first language, and Kincaid complains that even her critique of colonialism must be expressed in the words she learned from the colonialists themselves. Kincaid doesn’t feel at home in either world. She will never be truly English because of race and history, yet her intimacy with English culture expands her horizons far beyond the small boundaries of Antigua. Thanks to slavery and to being ruled from afar for so long, the

Antiguans have become accustomed to being passive objects of history, rather than active makers of it. The experiences of the colonized are therefore always secondary in some sense; it is the people from the “large places” who determine events, control history, and even control language. THE PREVALENCE OF CORRUPTION

For Kincaid, corruption is related to colonization in that it is a continuation of the oppression of colonialism—except that corruption turns the oncecolonized people against themselves. Kincaid insists that corruption pervades every aspect of public life in Antigua, that everyone knows about it, and that no one seems to know what to do about it. Government ministers run brothels, steal public funds, and broker shady deals, but there is a conspicuous lack of outrage on the part of the public. Kincaid attributes this lack of anger to the Antiguans’ general passivity, but she also sees their attitude as a logical reaction to the “lessons” of Antiguan history. The British claimed to be bringing civilization to the colonized territories while actually exploiting them and taking from them as much as they could. Naturally, when the Antiguans themselves came to power, they followed the example they had been given: under the motto “A People to Mold, A Nation to Build,” their ministers claim to be working for the greater good while lining their own pockets.

Motifs DIRECT ADDRESS TO THE READER

Kincaid speaks directly to the reader throughout A Small Place, even accusing the reader of taking part in the moral ugliness of tourism. Kincaid begins by describing what the reader might see and think as a visitor to Antigua, and she refers to what “you” are probably thinking as “you” read. This direct address has two effects. First, it emphasizes that, from the Antiguans’ point of view, the reader is just as much a part of a generalized group as they are, and that he or she will not be seen as an individual but as a stereotype. Second, it forces the reader to consider the ways in which he or she does, in fact, fit Kincaid’s stereotype of a tourist. Anyone who has traveled to the tropics in search of a relaxing “getaway” is likely to find reading A Small Place uncomfortable due to Kincaid’s accusing, sarcastic tone. By addressing the reader this way, Kincaid hopes to intensify her angry denunciation of the state of things in Antigua by pointing her finger directly at

the reader and anticipating the reader’s criticism. For Kincaid, any alienation that the reader feels is part of the plan. “UNREAL” BEAUTY Throughout A Small Place, especially in the...

Similar Free PDFs

A Small Place

- 10 Pages

A Small Place - Kincaid summary

- 5 Pages

Babcock Place - Grade: A

- 1 Pages

When Place Matters - Grade: A+

- 4 Pages

1.7 Description of a Place

- 1 Pages

Go Be (Place) - Grade: A

- 2 Pages

The South is a Place to Stay

- 8 Pages

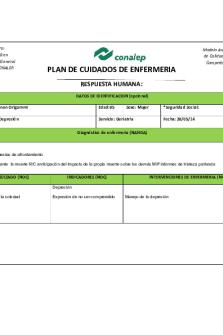

Depresion - PLACE

- 3 Pages

Asma - PLACE

- 2 Pages

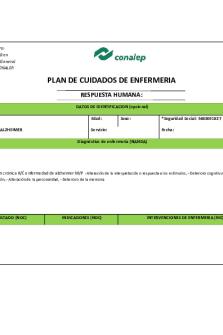

Alzheimer - PLACE

- 4 Pages

The tale of a small hedgehog

- 1 Pages

Geography/Place

- 3 Pages

Full Take off of a Small Bungalow

- 368 Pages

Small oscillations

- 22 Pages

Popular Institutions

- Tinajero National High School - Annex

- Politeknik Caltex Riau

- Yokohama City University

- SGT University

- University of Al-Qadisiyah

- Divine Word College of Vigan

- Techniek College Rotterdam

- Universidade de Santiago

- Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Johor Kampus Pasir Gudang

- Poltekkes Kemenkes Yogyakarta

- Baguio City National High School

- Colegio san marcos

- preparatoria uno

- Centro de Bachillerato Tecnológico Industrial y de Servicios No. 107

- Dalian Maritime University

- Quang Trung Secondary School

- Colegio Tecnológico en Informática

- Corporación Regional de Educación Superior

- Grupo CEDVA

- Dar Al Uloom University

- Centro de Estudios Preuniversitarios de la Universidad Nacional de Ingeniería

- 上智大学

- Aakash International School, Nuna Majara

- San Felipe Neri Catholic School

- Kang Chiao International School - New Taipei City

- Misamis Occidental National High School

- Institución Educativa Escuela Normal Juan Ladrilleros

- Kolehiyo ng Pantukan

- Batanes State College

- Instituto Continental

- Sekolah Menengah Kejuruan Kesehatan Kaltara (Tarakan)

- Colegio de La Inmaculada Concepcion - Cebu