Lala2011 - ccc PDF

| Title | Lala2011 - ccc |

|---|---|

| Author | Diem Pham |

| Course | Principles of marketing |

| Institution | Trường Đại học Kinh tế Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh |

| Pages | 18 |

| File Size | 466.7 KB |

| File Type | |

| Total Downloads | 47 |

| Total Views | 211 |

Summary

ccc...

Description

Journal ofhttp://jmd.sagepub.com/ Marketing Education When Students Complain: An Antecedent Model of Students' Intention to Complain Vishal Lala and Randi Priluck Journal of Marketing Education 2011 33: 236 originally published online 2 September 2011 DOI: 10.1177/0273475311420229 The online version of this article can be found at: http://jmd.sagepub.com/content/33/3/236 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for Journal of Marketing Education can be found at: Email Alerts: http://jmd.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://jmd.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://jmd.sagepub.com/content/33/3/236.refs.html

>> Version of Record - Dec 6, 2011 OnlineFirst Version of Record - Sep 2, 2011 What is This?

420229 and PriluckJo urnal o f Marketing Educatio n 33(3)

JM X

10.1177/0273475311420229Lala

Articles

When Students Complain: An Antecedent Model of Students’ Intention to Complain

Journal of Marketing Education 33(3) 236–252 © The Author(s) 2011 Reprints and permission: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0273475311420229 http://jmed.sagepub.com

Vishal Lala1 and Randi Priluck1

Abstract This article explores the factors that influence students’ intention to complain following a bad classroom experience using a customer service framework from the marketing literature. An online survey was conducted with 288 participants using the critical incident approach. Results indicate that predictors of intention to complain differ based on the target of complaint behavior (school, friends, or unknown others) and the mode of complaint (in person or using the web). Specifically, the more dissatisfied students are, the more likely they are to complain to the school and to friends either in person or using the web but not to unknown others. Students complain to the school only if the effort involved is minimal and they believe the school will respond. Students complain to friends and unknown others in person if they feel the school will respond to negative press. Personal characteristics also influence intentions to complain. Students with a propensity to complain broadcast their negative experience via the web, grade conscious students tell their friends but only in person, and heavy social media users inform their friends using the web. Implications for faculty and administrators are discussed. Keywords students, complain, web, structural equation modeling

According to the College Board (2009a, 2009b, see also Baum & Ma, 2007), in 20092010 the average tuition for a private 4-year college was $26,273, a yearly increase of 4.4%.

This research uses a customer service framework to analyze student responses and complaint behavior to negative classroom experiences. The framework is solidly grounded in the marketing literature and has been applied in a higher education context (Iyer & Muncy, 2008). Though not universally accepted, the student-as-customer perspective is popular

among researchers and universities (Gremler & McCollough, 2002; Iyer & Muncy, 2008). Although the relationship between a student and university is compatible with a customer service framework, it differs from typical service relationships (e.g., airline) in the difficulty of switching service providers. For instance, an unhappy customer can easily switch to a different airline. Students, on the other hand, face very high switching costs because of disruption of the educational process, difficulty in finding and applying to a new school, and adapting to a new physical and social surrounding. The student–university relationship may be emotionally charged, is often tied to relationships with friends and family members, and may influence an individual’s self-esteem. The act of choosing a college, paired with its high cost, leads to potentially high levels of student commitment and performance expectations. The nature of the relationship may make students more inclined to complain than exit (Singh, 1990). Since both college and high school students are highly engaged with social media, social networking provides an opportunity for and a potential threat to university recruitment. In 2008, 95.7% of college students 1

Pace University, New York, NY, USA

Corresponding Author: Vishal Lala, Lubin School of Business, Pace University, One Pace Plaza, W470, New York, NY 10038, USA Email: [email protected]

237

Lala and Priluck were online at least once a month (Planty et al., 2008), and teens who participate in social media are more likely to be influencers (myYearbook & Ketchum, 2010). The online behavior of students has a potentially strong impact on decisions of prospective students and may influence the attitudes of peers toward a university in both positive and negative ways. Social networking can lead to a shared college community, reinforcing the relationships students have with the school. However, when complaints are aired to friends and others, the university image may suffer. Importantly, the image of a college is a key driver of student satisfaction in college (Alves & Raposo, 2010). Naturally, universities are interested in identifying the factors that lead students to express their bad experiences online. Unlike students who complain to friends or air their grievances to others, students who complain directly give the school an opportunity for redress. Therefore, it is imperative that universities create the right conditions for students to complain directly to the school rather than to their friends and others. The purpose of this article is to use the marketing literature on consumer complaint behavior to identify the factors that influence students’ likelihood to complain to the school, friends, and others, both in person and using the web. The findings will help faculty and administrators in managing student dissatisfaction and complaint behavior.

Conceptual Framework and Hypotheses Determinants of Student Satisfaction Student satisfaction with college comprises a number of factors. Researchers have recently examined student satisfaction with the curriculum and instruction, extracurricular activities, career opportunities, advisement, social connectedness, instructor feedback, level of technology, other students, involvement and engagement, approachability of faculty and staff, and individual student self-confidence (Letcher & Neves, 2010; Roberts & Styron, 2010). However, Elliot (2003) suggests that the two most important factors influencing student satisfaction are: student centeredness and instructional effectiveness. Michalos and Orlando (2006) found that the most powerful predictor of student satisfaction was satisfaction with instructors, the emphasis of this research. Professors have the opportunity to build trust and attachment with students, leading to higher levels of satisfaction. Such students may serve as advocates for the professor (Jillapalli & Wilcox, 2010).

Student Responses to Negative Classroom Experiences The marketing literature suggests that product or service failure may result in three possible customer responses: exit,

voice, or loyalty. Exit refers to severing the tie with the marketer by choosing a competitor, voice includes both internal and external complaining, and loyalty suggests suffering in silence (Singh, 1990). Students may respond in each way, but because of the difficulties inherent in leaving a university, they are most likely to engage in complaint behavior or loyalty following a negative classroom experience (Day, Grabicke, Schaetzle, & Staubach, 1981; Nyer & Gopinath, 2005). Using the exit, voice, and loyalty framework, Su and Bao (2001) characterized student complaint behavior as a result of negative experience with faculty based on three responses. Passive recipients suffer in silence, whereas private complainers discuss the dissatisfaction with friends and family. The most vocal group—the voicers—complain to friends and family as well as to the professor and administrators. Voicers hold less respect for professors’ punishment and legitimate power and higher positive attitudes toward complaining overall. The services literature has identified another category of complaint behavior—complaints directed at strangers (Singh, 1988). Based on a factor analysis of complaining behaviors across four service categories, Singh (1988) identified three distinct categories of complaint behavior: complaints to the seller, negative word-of-mouth, and third-party responses. This taxonomy has been validated in studies that have shown differences in the etiology of the three categories of complaint behavior (Singh & Wilkes, 1996). To make this taxonomy relevant to the context of student complaining behavior, we label these three categories as complaints directed at the school, friends, and others. Complaints directed at the school include attempts by the student to inform school administrators (e.g., dean, department chair), professors, or advisors about the troubling incident. Complaints directed at friends involve sharing the experience with friends, people the student knows. We do not refer to this as negative word-of-mouth communication, since the latter has also been used to include behaviors such as creating hate websites and spamming, where the target of the message may not be known to the user. Complaints directed at others include attempts to share the experience with people the student does not know using outlets such as a newspaper editorial or pursuing legal action (e.g., Singh, 1988).

Channels of Complaint Behavior With the emergence of the web and the availability of Internet technologies such as e-mail, students may also share their experiences through the web. Students have the option of complaining to the school in person by meeting with a professor or advisor or using the end-of-semester instructor evaluation form. Another way students can express their grievances is by using the web to e-mail a professor or using a web-based feedback system managed by the university.

238

Journal of Marketing Education 33(3)

Table 1. Channels of Complaint Behavior Channel Complain to school in person Complain to school using the web Complain to friends in person Complain to friends using the web Complain to others in person Complain to others using the web

Description Complain to school administrator (e.g., dean, department chair), professor, or advisor by meeting them in person Complain to school administrator (e.g., dean, department chair), professor, or academic advisor by contacting them using web-based technology such as e-mail Inform friends or other students by meeting them in person or over the phone Inform friends or other students by e-mail, instant messaging, or via a social networking website (e.g., status message on Facebook) Broadcast experience to unknown others by writing to the school paper, posting flyers around school, or taking legal action Broadcast experience to unknown others by creating a hate website (e.g., sucks. com), posting messages to a listserv, posting to a public blog, rating the professor on a professor evaluation website (e.g., ratemyprofessor.com), or creating a public group on a social networking website such as Facebook

Similarly, students can complain to their friends in person when they meet them, by calling them, or by texting them. Alternatively, students can e-mail their friends or share their experience with their friends on social networking platforms such as Facebook or MySpace. Finally, students can complain to others by using traditional options such as pursuing legal action, an article in the local newspaper, and posting flyers across campus, or they can use the web by creating a hate website, sending e-mails to a listserv, posting to a public blog, rating the professor on a professor evaluation website (e.g., RateMyProfessor.com), and creating a public group on Facebook. Broadly speaking, students can address their complaints to the school, friends, and others, either in person or using the web. We use the phrase “in person” to refer to all traditional modes of complaining including faceto-face interactions, phone conversations, text messaging, and writing an article in the local newspaper. We use the phrase “using the web” to refer to all web and Internet technologies including e-mail, instant messaging, creating a website (e.g., sucks.com), rating a professor on a website, posting or creating a blog, posting or reading tweets, and participating in a social networking website (e.g., Facebook). Web-based modes of communication differ from in-person modes of communication in a number of ways including convenience, ease, and sophistication. Moreover, we believe that just as complaining to different people (e.g., school, friends, and others) has been demonstrated to have different etiologies (Singh & Wilkes, 1996), so do complaining in person and by using the web. Accordingly, we propose a taxonomy defined by the target of the complaint and medium used. Thus, with three targets of the complaint and two media, we have six different ways that students can complain in response to a bad experience: complain to the school in person, complain to the school using the web, complain to friends in person, complain to friends using the web,

complain to others in person, and complain to others using the web. See Table 1 for a summary of the six channels of complaint behavior.

The Importance of Student Expectations to Predict Satisfaction As with most consumption situations, student assess their levels of satisfaction with a course and are prompted to do so when they are asked to evaluate the professors. K. J. Kim, Liu, and Bonk (2005) suggest that students’ satisfaction with a course is related to students’ perceptions of learning, students’ sense of community within the class, their levels of engagement in learning, various learning techniques, individual academic confidence, and prompt feedback from the instructor. Other research suggests that rapport between a professor and students leads to higher levels of engagement, learning, and other positive benefits (Granitz, Koernig, & Harich, 2009). Expectations theory provides some insight into how students may respond to service encounters (Bolton & Drew, 1991). Specifically, Appleton-Knapp and Krentler (2006) examined the relationship between student expectations and satisfaction by measuring expectations at the start of the term and comparing those expectations with recalled expectations and current perceptions at the end of the term. The findings suggest that recalled and current expectations are stronger predictors of satisfaction than previously determined expectations. Similarly, consumers develop a set of expectations about consumption experiences, and when those expectations are not met they may be dissatisfied. A number of studies have found that in retail services, negative disconfirmation leads to dissatisfaction (Swan & Trawick, 1981; Teas, 1993). Smart, Kelley, and Conant (2003) suggest that student expectations of faculty are rising, and one study found that

239

Lala and Priluck students hold higher expectations for their institutions than faculty (Shank, Walker, & Hayes, 1996). Studies have found that a blatant marketer-caused failure may lead to an emotional response, followed by a possible backlash against the marketer (Stephens & Gwinner, 1998). Similarly, dissatisfied students may engage in negative word of mouth (Su & Bao, 2001). However, widespread complaining to others on the Internet may lead to a devaluation of the reputation of the institution and students’ degrees, suggesting less incentive for students to engage in such behavior relative to other consumption situations.

Dissatisfaction and Complaint Intentions A key attribute in determining complaint behavior among service customers is dissatisfaction. A number of studies have found relationships between dissatisfaction intensity and complaining or complaint intentions (Bearden & Teel, 1983; Mittal, Huppertz, & Khare, 2008; Richins, 1983; Voorhees & Brady, 2005). Richins (1983) found that as dissatisfaction grows, the tendency to engage in negative word-of-mouth increases. Funches, Markley, and Davis (2009) found that when consumers are dissatisfied, they may not limit themselves to just negative word-of-mouth but may also display more extreme retaliatory behaviors. Jacobs (1996) found that highly dissatisfied cable subscribers tended to complain more than those who were less dissatisfied. Similarly, Cho, Im, Hiltz, and Fjermestad (2002) found that the extent of dissatisfaction influences propensity to complain. Underscoring the importance of dissatisfaction is the finding by Blodgett, Wakefield, and Barnes (1995) that dissatisfaction is the single most important factor influencing the likelihood to complain either internally or externally. In a university setting Oliver (1986) found a relationship between dissatisfaction among MBA students and complaints to administrators, faculty, and advisors. Kara and DeShields (2004) found that dissatisfaction has a direct effect on students’ decision to remain enrolled at the university, and Michalos and Orlando (2006) suggest that faculty play the strongest role in determining satisfaction/ dissatisfaction among students. In general, researchers agree that dissatisfaction is a prerequisite to complain behavior. For example, Singh (1988) describes consumer complaint behavior as a set of responses triggered by dissatisfaction with a purchase episode. However, some researchers have questioned the role of dissatisfaction intensity. Specifically, does greater dissatisfaction lead to more complaining behavior? Singh and Pandya (1991), who examined this question, found that the extent of dissatisfaction is linearly related to complaints to the service provider, but with regard to complaints directed at others, they found evidence of a threshold effect. Specifically, they found a strong effect between dissatisfaction intensity and complaint behavior once dissatisfaction exceeded a certain tolerance level.

There are numerous motivations for engaging in negative word-of–mouth—for example, to benefit others, to pacify hurt egos, to establish cognitive clarity, to appear wellinformed, and to reduce cognitive dissonance (Richins, 1983). The need for reassurance in the face of a negative classroom experience may motivate students to complain to family and friends, particularly when students can do little to change a grade or a professor’s attitude. The perceptions of faculty power and the tenure system may prevent students from approaching professors with complaints. Negative word-of-mouth in marketing situations tends to strongly influences others because of perceptions of unbiased information (Richins, 1983) and individual’s natural risk aversion. Powerlessness in a service situation may lead to grudge holding, retaliation, and fear on the part of consumers, particularly when there are high exit barriers (Bunker & Ball, 2009; Bunker & Bradley, 2007). Venting to friends and family following a classroom situation over which they have little control may make students feel more powerful. Recent research on student complaint behavior suggests that students vary their complaining based on perceptions of power. Specifically, students’ perceptions of strong referent (expert) power leads to higher levels of complaining than students’ beliefs regarding professors’ reward or punishment power (Mukherjee, Pinto, & Malhotra, 2009). Today’s online environment provides many opportunities to voice complaints. There is no intuitive reason to expect differences in the relationship between dissatisfaction and intentions to complain in person and using the web nor is there any literature to guide a hypothesis that predicts differences. Therefore, we make similar predictions for intentions to complain in person and using the web. Finally, our methodology en...

Similar Free PDFs

Lala2011 - ccc

- 18 Pages

CCC revision

- 106 Pages

Cuenta 16 - ccc

- 4 Pages

Tutorial 3 - ccc

- 1 Pages

CCC Written Essay Assignment

- 5 Pages

Case 3- CCC

- 6 Pages

VI Manual ACTy CCC

- 190 Pages

CCC Computer online Test

- 24 Pages

Final DE T2 Costo - ccc

- 18 Pages

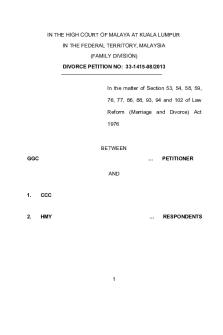

GGC v CCC & Anor - A case law.

- 75 Pages

Week 3 CCC Parts 2 & 3 Template

- 3 Pages

SAN JUAN, Julia MAE - ASS-CCC

- 3 Pages

Popular Institutions

- Tinajero National High School - Annex

- Politeknik Caltex Riau

- Yokohama City University

- SGT University

- University of Al-Qadisiyah

- Divine Word College of Vigan

- Techniek College Rotterdam

- Universidade de Santiago

- Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Johor Kampus Pasir Gudang

- Poltekkes Kemenkes Yogyakarta

- Baguio City National High School

- Colegio san marcos

- preparatoria uno

- Centro de Bachillerato Tecnológico Industrial y de Servicios No. 107

- Dalian Maritime University

- Quang Trung Secondary School

- Colegio Tecnológico en Informática

- Corporación Regional de Educación Superior

- Grupo CEDVA

- Dar Al Uloom University

- Centro de Estudios Preuniversitarios de la Universidad Nacional de Ingeniería

- 上智大学

- Aakash International School, Nuna Majara

- San Felipe Neri Catholic School

- Kang Chiao International School - New Taipei City

- Misamis Occidental National High School

- Institución Educativa Escuela Normal Juan Ladrilleros

- Kolehiyo ng Pantukan

- Batanes State College

- Instituto Continental

- Sekolah Menengah Kejuruan Kesehatan Kaltara (Tarakan)

- Colegio de La Inmaculada Concepcion - Cebu